Cabinet of Curiosities

Online Biology Dictionary

|

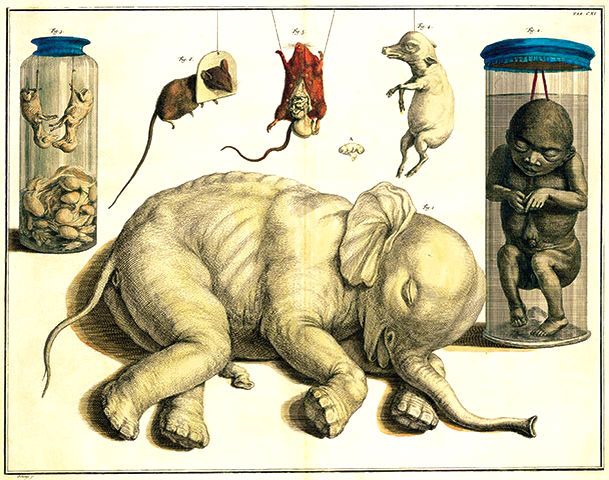

| Above: Items from the cabinet of Albertus Seba |

|

|

|

…a tortoise hung,

An alligator stuff'd, and other skinsof ill-shaped fishes…

—Shakespeare

Romeo and Juliet (V. i) |

|

|

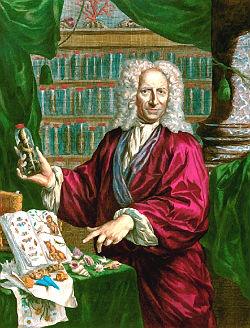

Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605) |

A cabinet of curiosities was an extensive collection of objects considered surprising for their novelty or of interest in some other way. It was a cabinet in the old sense of the term, that is, a room with restricted access. Only the wealthy possessed such collections, given that they were so expensive to assemble, hence the restrictions.

Typically, the items on display were preserved organisms, or parts of organisms, including fossils, various minerals, and human productions, particularly the products of foreign cultures, as well as art and antiquities. Cabinets of curiosity, which were the precursors of modern museums, were also known as wonder-rooms, Wunderkammern, or Kunstkammern. However, unlike museums as we know them, such collections usually were not open to the general public.

One of the earliest and most impressive cabinets, comprising more than 7,000 specimens, was assembled in the sixteenth century by the Italian naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605). In his prolific works on natural history, Aldrovandi described not only organisms that actually exist, but also many that do not. His collection also contained many fakes that he apparently purchased in the belief they were real. Nevertheless, despite his gullibility on such matters (a trait he shared with the vast majority of his contemporaries), he is regarded as one of the founders of modern biology. A remnant of his collection, now much ravaged by time, is still on display in the Palazzo Poggi, a museum in Bologna.

|

|

Albertus Seba (1665-1736) |

In the eighteenth century, Albertus Seba, an internationally famous apothecary, amassed a huge collection of curiosities. German by birth, during his early years, he traveled over much of the earth and returned with oddities of every kind. After his voyages, he established himself as a druggist in a shop on the harbor in Amsterdam. He would board newly arrived ships, ostensibly to supply medicines and to purchase materials for making drugs, but then dicker with the sailors over natural treasures they had brought from afar. He usually acquired them for a fraction of their worth.

Seba eventually became a wealthy man. In 1717 he sold his entire collection to the Russian Czar Peter the Great, who carried it all off to St. Petersburg. But then Seba just kept on collecting until his cabinet was again full to bursting, bigger and better than ever before. Together with the collection of Frederik Ruysch, another well-known Amsterdam collector, Seba's cabinet of curiosities formed the original core of the Kunstkammer, the first Russian public museum. In 1735 Linnaeus viewed his collection, and it became one of the bases on which he began to develop his new system of classification.

Cabinet of Curiosities © Macroevolution.net

Most shared on Macroevolution.net:

Human Origins: Are we hybrids?

On the Origins of New Forms of Life

Mammalian Hybrids

Cat-rabbit Hybrids: Fact or fiction?

Famous Biologists

Dog-cow Hybrids

Georges Cuvier: A Biography

Prothero: A Rebuttal

Branches of Biology

Dog-fox Hybrids