Camel hybrids

Family Camelidae

Mammalian Hybrids

Mammalian Hybrids

Camel hybrids (Family Camelidae) are covered in this section of Mammalian Hybrids. The camel family includes the Dromedary, the Bactrian Camel, the Guanaco (and its domestic derivative, the Llama), the Vicuña, and the Alpaca.

Camelus dromedarius

Camelus sp. [Camel]

× Bos taurus [Domestic Cattle] One report about camel-cow composite appeared in the Réveil de Mauriac (Mauriac, Feb. 4, 1899, p. 3b) that claimed a cow had recently calved an animal that was a virtual camel ("une vache a produit un véritable petit chameau"). Another, which may refer to the same case, appeared in La Charente (Angoulême, Mar. 29, 1899, p. 2). It described a diminutive calf with a camel-like hump in the middle of its back. Calved at Saint-Yrieix-La-Perche, Haute-Vienne, it was eight months old. Another French report (,Journal de Villefranche Villefranche-sur-Saône, Jan. 17, 1903, p. 2f; ||4tva3hfn), difficult to interpret, says a cow in the commune of Grandis, 30 km west of Villefranche-sur-Saône, calved an animal that was mostly like a camel but that had the head of a boar. Another French report (Le Réveil du Beaujolais, Villefranche-sur-Saône, Oct. 17, 1913, p. 2d-e; ||4n5zkbbv), equally opaque, tells of an animal calved by a cow at Ville-sur-Jarnioux in 1913, in which the head and body were supposedly covered with long goat hair, and that had on its back two humps like a camel's. La Bourgogne républicaine (Dijon, Jun. 26, 1953, p. 2d; ||5vn9jrx2) reported an animal calved at Montigny-sur-Aube, Côte-d'Or, France, that had a camel's hump and deformed hoofs.

× Equus caballus [Domestic Horse] See the separate article "Camel-horse Hybrids."

Camelus bactrianus [Bactrian Camel]

× Camelus dromedarius (↔ usu. ♀) [Dromedary] CHR. See the separate article “Bactrian Camel × Dromedary.”

Camelus dromedarius [Dromedary]

See also: Camelus bactrianus.

× Homo sapiens [Human] See the separate article “A Camel-human Hybrid?.”

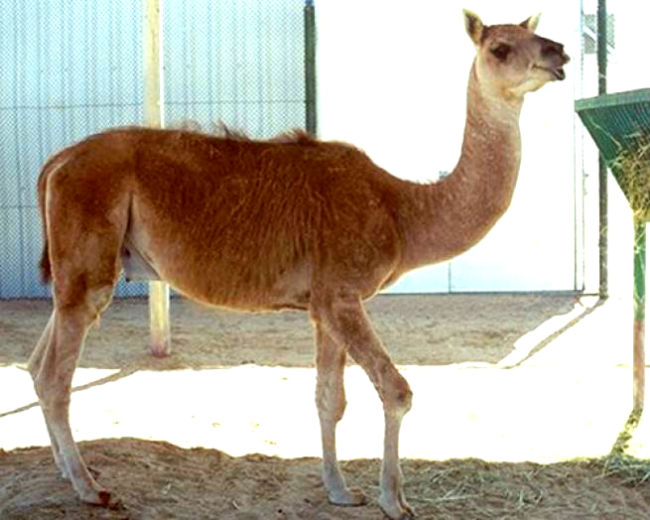

× Lama guanicoe (♀) [Guanaco] CHR. DRS. Guanaco-camel hybrids are known as a “camas” (from camel × llama—the llama is the domestic derivative of the guanaco). In 1997 a male hybrid was produced by artificial insemination. When mature, it had the muzzle features and fine quality coat of the New World camelids. It also lacked a hump. Vocalizations were deep like a dromedary instead of the high pitched as in a guanaco. Two female hybrids have since been produced. Gestation lasts 11 months in guanacos, 13 in dromedaries. Dromedary males are about six times the size of guanaco females. A much earlier example of a camel-llama hybrid is mentioned in an 1871 newspaper article (See: The Ogdensburg Journal, August 25, 1871, p. 3). Skidmore et al. 1999, 2001†.

×Panthera pardus [Leopard] In ancient times, as well as later, in the medieval era, it was believed that giraffes were the product of this cross. Thus, the Greco-Roman poet Oppian (Cynegetica, III), referring to giraffes (also known as camelopards), wrote "Tell also, I pray thee, O clear-voiced Muse of diverse tones, of those tribes of wild beasts which are of hybrid nature and mingled of two stocks, even the Pard of spotted back joined and united with the Camel." However, no such hybrid is known.

×Sus scrofa [Domestic Pig] Giambattista della Porta (Natural Magick, p. 41), the Renaissance scholar, polymath and playwright, citing Didymus Chalcenterus (c. 63 BC – c. AD 10), claimed that Bactrian camels were originally produced by hybridizing boars with dromedaries. There seems to be no modern evidence that such a cross is possible, so Porta's assertion is included here only as an historical note.

A guanaco/dromedary camel hybrid (cama)

A guanaco/dromedary camel hybrid (cama)

|

|

|

Llama (Lama glama) |

|

|

|

Guanaco (Lama guanicoe) |

|

|

|

Alpacas (Vicugna pacos) |

Lama glama [Llama]

+ Capra hircus [Domestic Goat] Although various later authors cite Pietro Rossi (1799, pp. 120-121) as having claimed that a male llama crossed with a goat doe to produce a hybrid, an examination of Rossi’s paper revealed that he merely quoted from Pietro Andrea Mattioli’s Epistolarum Medicinalium Libri Quinque (1561) to the effect that a male llama in captivity, deprived of females of its kind, mounted and inseminated a goat, but without a hybrid being produced.

× Lama guanicoe (↔ usu. ♂) [Guanaco] CHR. HPF. The llama is a domestic animal, but feral llamas come into contact with guanacos in the Andes. Antonius 1951b; International Zoo Yearbook 1961, 1962, 1965, 1966, 1967, 1968, 1969, 1970, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1974, 1975, 1977, 1978, 1981, 1989; Link 1948; Maccagno 1932†; Mascheroni 1941; Neuhaus 1942; Taworski and Wolinski 1960.

× Vicugna pacos (↔) [Alpaca] CHR. Hybrids are partially fertile in both sexes. The “huarizo” (male llama × female alpaca) is more often bred than the “misto” (male alpaca × female llama). Flower (1929a, p. 332) notes that a hybrid was presented to the London Zoo as early as 1844. The huarizo is used in some parts of Peru as a beast of burden and is a significant source of exported wool. Ackermann 1898; International Zoo Yearbook 1980 (p. 438), 1983 (p. 331), 1984/1984 (p. 548); Link 1949; Maccagno 1932; Mascheroni 1941; Neuhaus 1942; Przibram 1910; von Bergen and Stevens 1963 (p. 386).

× Vicugna vicugna [Vicuña] CHR. Hybrids are partially fertile in both sexes. This cross is common in the Andes. The hybrids are known as waris. Grubb (in Wilson and Reeder 1993) expressed the opinion that the alpaca (Vicugna pacos) is derived from this cross. More information >>

Lama guanicoe [Guanaco]

See also: Camelus dromedarius; Lama glama.

× Vicugna pacos [Alpaca] CHR. CON: South America. International Zoo Yearbook 1969 (p. 234), 1971 (p. 280), 1973 (p. 337).

Note: The alpaca is a domestic animal produced by human breeding.

Vicugna pacos [Alpaca]

See also: Lama glama × Vicugna vicugna; Lama guanicoe.

× Vicugna vicugna (↔) [Vicuña] CHR. Hybrids are partially fertile in both sexes. CON: Peru. In the Andes, where this cross is common, the hybrids are known as “pacovicuñas.” Their wool is superior to that of the alpaca, and the fleece is heavier than the vicuña’s. To produce them, breeders intentionally imprint a male vicuña on alpacas by rearing them with an alpaca (hybrids produced from matings between a female vicuña and an alpaca lack commercial value). Newborn vicuñas must be obtained by hunting since vicuñas are not domesticated. “Thus,” says de Macedo, “a native shepherd-hunter first spots a flock of pregnant vicuñas at the proper season (January to March) and then waits daily for the instant of parturition,” when he quickly approaches with dogs and attempts to lasso the newborn (which will soon be able to run as fast as its mother). For rearing, these captured vicuñas are given to a lactating alpaca that has lost her calf. During the introduction, care is taken to cover the young vicuña with the skin of a young alpaca to prevent rejection by the prospective foster mother. According to the IUCN, “A new potential threat, both in the Andes and worldwide, is the breeding of pacovicuña (an Alpaca/Vicuña hybrid) for commercial purposes (Lichtenstein, Hoces and Wheeler presentations to the Vicuña Convention).” Gray (1972, p. 163) states that the fleece of a pacovicuña is “finer than that of the alpaca but much lighter, although heavier than the fleece of a vicuña. The wool loses its fineness, however, after the first shearing, when the percentage of coarse hairs increases.” Ackermann 1898 (pp. 59-60); Bonadonna et al. 1967; Chang et al. 1969; de Macedo 1982†; Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire 1849; International Zoo Yearbook 1960 (p. 263), 1971 (p. 280), 1972 (p. 334), 1973 (pp. 337, 386), 1978 (p. 393), 1980 (p. 438); Link 1920, 1948, 1949; Maccagno 1932; Mascheroni 1941. More information >>

Vicugna vicugna [Vicuña] See: Lama glama; Vicugna pacos.

By the same author: Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World, Oxford University Press (2006).

Camel Hybrids - © Macroevolution.net

Most shared on Macroevolution.net:

Human Origins: Are we hybrids?

On the Origins of New Forms of Life

Mammalian Hybrids

Cat-rabbit Hybrids: Fact or fiction?

Famous Biologists

Dog-cow Hybrids

Prothero: A Rebuttal

Branches of Biology

Dog-fox Hybrids