Bird × Fish

Above: A stange bird-headed fish netted from a river in the province of Guizhou in southwestern China in June 2018.

Above: A stange bird-headed fish netted from a river in the province of Guizhou in southwestern China in June 2018.|

And yet a little voice had begun to niggle at the back of my mind; it said I knew nothing, nothing at all.

—James Herriot

All Creatures Great and Small |

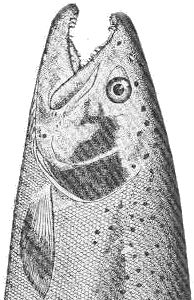

A purported bird-fish hybrid caught in China, June 6, 2018. Note that its mouth can be seen gaping as it gasps for air.

A purported bird-fish hybrid caught in China, June 6, 2018. Note that its mouth can be seen gaping as it gasps for air.

Caution: Although videos showing a living ostensible hybrid are available, the actual occurrence of this distant cross has not been confirmed via genetic testing of a specimen.

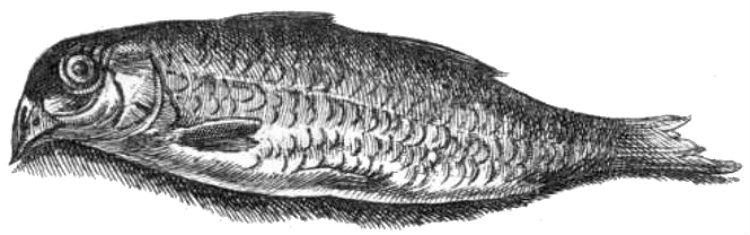

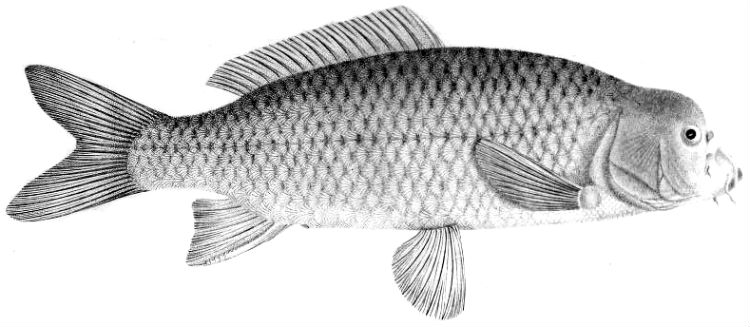

In the summer of 2018, from a river in the province of Guizhou in southern China, fishermen netted a strange creature with the body of a fish and the head of a bird (see photo above and video at right). In connection with this catch, a Chinese news source (translated by Google) stated that “A few fishermen who love fishing in Guizhou have recently encountered a magical event. They caught a fish with a bird’s head. Out of respect for life, they finally released the fish.” The same source identifies the fishlike body of the creature as that of a grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella), which seems to agree with the photos. But the creature’s head far departs from that of any ordinary carp. There was online debate about whether its head looked more like a dolphin’s or a bird’s. Another, lower-resolution picture appears below, showing this creature in full profile, which accentuates the bird-like appearance of the head.

The Guizhou catch compared to an ordinary grass carp

The Guizhou catch compared to an ordinary grass carp

A German specimen

The Guizhou catch went viral more than two centuries after the French physician and naturalist René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur (1683-1757) described another case of what seemed to be a bird-fish hybrid, this time caught in Germany. In 1747, at a meeting of the French Royal Academy of Sciences de Réaumur presented a drawing of a strange fish with the body of a carp and a head, he thought, like that of a wagtail. Wagtails (genus Motacilla) are insectivorous birds, often found near water. In translation, an account of de Réaumur's presentation, recorded five years after the fact in the Histoire de l’Académie Royale des Sciences (1752, pp. 52-53), reads,

de Réaumur

de Réaumur

White Wagtail

White Wagtail Common Carp

Common CarpOne of the foremost scientists of his day, de Réaumur was a Fellow of the Royal Society. Over the years, he collected what may have been the most extensive cabinet of curiosities then in existence.

Hamberger

Hamberger

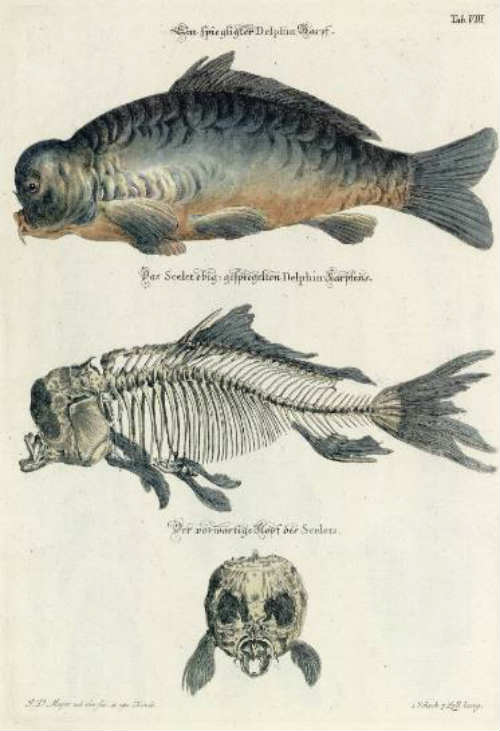

It seems that de Réaumur obtained his information from a report (Georgii Erhardi Hambergeri ... Propemticon inaugurale de cyprino monstroso rostrato, 1748) written by Georg Erhard Hamberger (1697-1755), a German physician who was a member of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Jena, where he twice served as the university’s Rector (that is, as its head official). His report provides much the same information as that provided in the account of de Réaumur’s presentation already quoted. In addition, however, it includes a copper plate etching of the animal, which shows that this tertium quid did in fact have a birdlike beak (see below), which Hamberger described as "sharp, hard and similar to the beak of a sparrow" ("acutum, durum, rostro passeris simile").

The bird-headed carp reported by Hamberger (image source).

The bird-headed carp reported by Hamberger (image source).

Friedrich III

Friedrich IIIDuke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg

Since Hamberger states that Duke Friedrich (Friedrich III, Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg) had the creature preserved in alcohol after its death (it lived for a few days after it was caught) and placed in his Wunderkammer,† it’s conceivable that this specimen survives today. If so, it would still be possible to extract DNA and positively identify its parentage, especially since it would, in all likelihood, be an F1 hybrid (if, that is, it actually is a hybrid). It seems likely that Hamberger saw this specimen himself since the Duke’s seat at Gotha is only about fifty miles from Jena, and since the drawing of the specimen was signed by a Jena artist.

How could mating have occurred?

The White Wagtail, Motacilla alba, is the most common wagtail in Germany where the specimen was collected, and it is, moreover, extremely widespread in Eurasia. It is mostly aquatic in its choice of habitat and is commonly seen feeding and breeding along the edges of lakes and streams. Thus, a male wagtail while mating with females along the shore might easily release semen from his cloaca into the water, and so, from time to time, fertilize a carp egg. This seems more likely in view of the fact that carp are extremely fecund. The Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio), which is also widespread in Europe and Asia, has a typical clutch size of about 300,000 eggs, but a single female may lay as many as 2,000,000 eggs at a time. The density of carp eggs during spawning season, then, must be incredibly high.

A third ostensible bird-fish hybrid

Another fish with a birdlike head (see image below) was reported by Gaston Carlet (1879), a member of the French Faculty of Medicine and a professor in the School of Medicine at Grenoble. This specimen, however, had a body like that of a trout instead of a carp. It was found in a lake in the upper Isère Valley (France) at an altitude of 2,000 meters. Carlet (p. 160) mentions that the fishermen who caught this specimen insisted that they had caught others like it in the past and that it must therefore "represent a new species." He also states (p. 157) that the lower jaw (mâchoire inférieure) was like that of any other trout, only it was slightly shorter than the usual given the size of the fish. Note that what appears to be the upper portion of a bird beak is visible in Carlet’s illustration.‡ Given the locale where the specimen was collected, Oncorhynchus mykiss, the rainbow trout, would likely have been the specific fish in question.

|

|

|

Beakless specimens

In addition, there are specimens on record, such as the middle specimen (from Yarrell 1841, p. 108) pictured next to Carlet's specimen above, which resemble those just discussed only with respect to the rounded structure of the forehead (frontal region), but which do not have birdlike mandibles. However, the resemblance of the strongly rounded, or bulging, forehead is in fact marked. Regarding such fish, Yarrell (1841, pp. 107-108) states that

So one can see that the specimen figured by Yarrell, with its rounded forehead is, because it lacks an upper beak like bird’s, intermediate in form between an ordinary trout and Carlet’s specimen which has. (Note, too, that the Britannica’s statement that these trout never grow large is consistent with the idea that these are relatively inviable hybrids derived from a distant cross.)

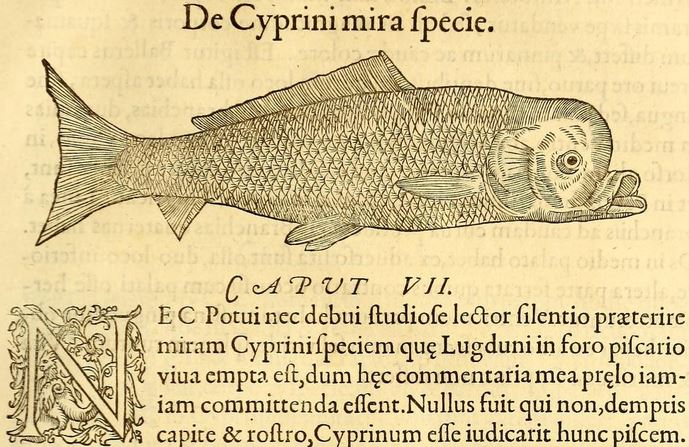

"A remarkable carp" ("Cyprinus mira specie") pictured by the early naturalist Guillaume Rondelet (1555, p. 154). Rondelet says it was purchased alive at the Lyon fish market and that without its head it would have been indistinguishable from an ordinary Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio). However, he thought its rounded forehead was like that of a dolphin.

"A remarkable carp" ("Cyprinus mira specie") pictured by the early naturalist Guillaume Rondelet (1555, p. 154). Rondelet says it was purchased alive at the Lyon fish market and that without its head it would have been indistinguishable from an ordinary Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio). However, he thought its rounded forehead was like that of a dolphin.

Guillaume Rondelet

Guillaume RondeletIn addition to Yarrell’s specimen, there are cases on record that resemble Carlet’s specimen (and the Chinese and German specimens) with respect to the rounded structure of the forehead, but which do not have protruding lower mandibles nor birdlike beaks. One such was pictured by the early anatomist and naturalist Rondelet (see image above).

It may be that these beakless specimens represent one grade of the variation found in bird-fish hybrids (that is, if such hybrids exist at all!). Thus, one can recognize a series in which (1) the Chinese and German specimens have a rounded forehead and both upper and lower mandibles birdlike; (2) Carlet’s has a similarly rounded forehead, and birdlike upper mandible, but a fishlike lower mandible; (3) in Yarrell’s, in Rondelet’s, and in the specimens about to be discussed, neither mandible is birdlike, but the foreheads do closely resemble those of the specimens already described.

Conrad Gesner (1516–1565), the Swiss naturalist, briefly describes another specimen similar to Rondelet’s, taken from a lake at Nozeroy, a village in eastern France, in February of 1554 (Historia Animalium, Liber IV, p. 374, 30). He states that it was sent to him by Gilbert Cousin de Nozeroy (Gilbertus Cognatus Nozerenus), the secretary of Erasmus.

And two centuries later, Johann Daniel Meyer (1752, pp. 12-14) discussed and pictured a carp of the same sort (Meyer’s illustrations are reproduced below), which he said were known in German as Mopskarpfen or Delphinkarpfen. This individual, too, other than its cranium, was like a Common Carp (Meyer’s pictures of an Common Carp are also shown below for comparison).

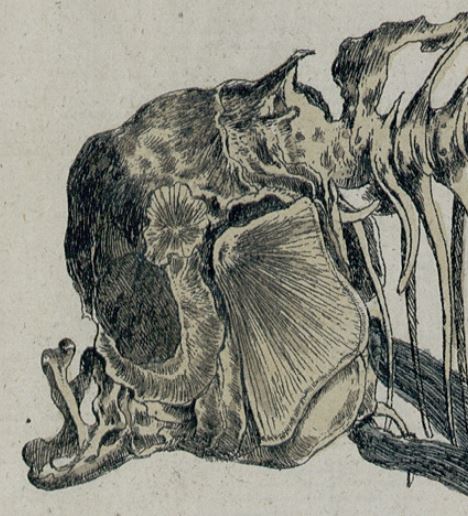

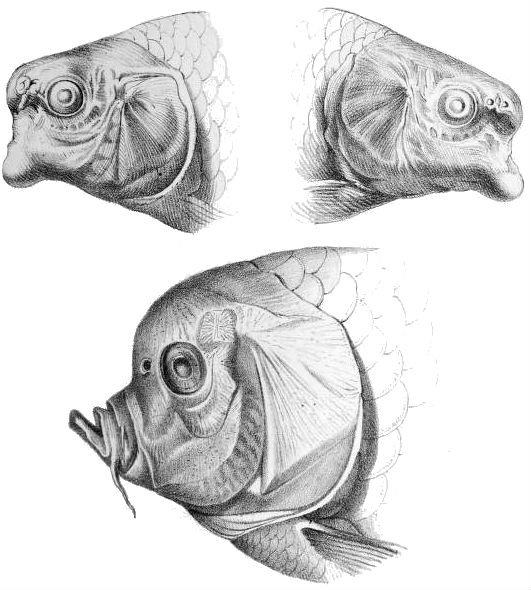

Enlarged view of the head of the abnormal specimen, which is pictured in its entirety below (source: Meyer 1752, 85:VIII).

Enlarged view of the head of the abnormal specimen, which is pictured in its entirety below (source: Meyer 1752, 85:VIII).

Head of an ordinary Common Carp for comparison with the abnormal specimen pictured immediately above (source: Meyer 1752, 83:VII).

Head of an ordinary Common Carp for comparison with the abnormal specimen pictured immediately above (source: Meyer 1752, 83:VII).

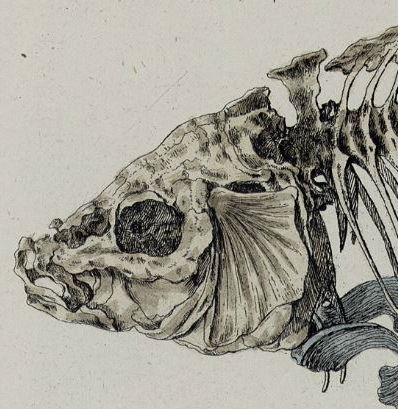

Enlarged lateral view of the skull of the abnormal specimen pictured, which is pictured in its entirety below (source: Meyer 1752, 85:VIII).

Enlarged lateral view of the skull of the abnormal specimen pictured, which is pictured in its entirety below (source: Meyer 1752, 85:VIII).

Enlarged lateral view of the skull of an ordinary Common Carp for comparison with the abnormal specimen pictured immediately above (source: Meyer 1752, 83:VII).

Enlarged lateral view of the skull of an ordinary Common Carp for comparison with the abnormal specimen pictured immediately above (source: Meyer 1752, 83:VII).

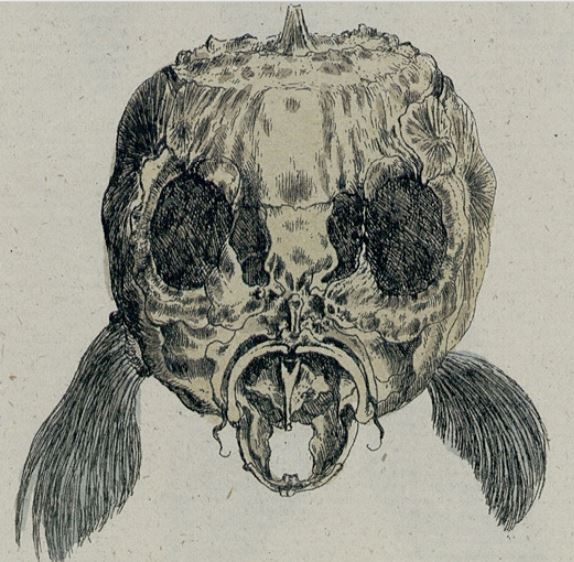

Enlarged frontal view of the skull of the abnormal specimen, which is pictured in its entirety below (source: Meyer 1752, 85:VIII).

Enlarged frontal view of the skull of the abnormal specimen, which is pictured in its entirety below (source: Meyer 1752, 85:VIII).

Meyer's original illustration (source: Meyer 1752, 85:VIII).

Meyer's original illustration (source: Meyer 1752, 85:VIII).

Abnormal carp pictured in Neydeck (1849, p. 23). Blanchard (1866, p. 330) stated that among carp this deformity is one of those most commonly encountered.

Abnormal carp pictured in Neydeck (1849, p. 23). Blanchard (1866, p. 330) stated that among carp this deformity is one of those most commonly encountered.

In addition, Neydeck (Neydeck 1849) reported a carp with a bulging forehead caught in the Neckar River at Mannheim on October 2, 1817. From its picture (above), it can be seen that, while less pronounced, it was quite similar to the one Rondelet had reported three centuries earlier. Neydeck says that it lived for two weeks, and that after it died he preserved it in alcohol and eventually donated it to Mannheim’s natural history museum. So the specimen may still exist in a modern collection in that city, perhaps the Reiss-Engelhorn-Museen Mannheim. It's of interest that Neydeck specifically states that this specimen had no scales on its head, which was also the case with the Chinese specimen. Patterson (1896, p. 100) briefly reports a similar deformity in a cod.

And Steindachner (1863) pictures the heads (see images below) of three separate fish similar to the others discussed on this page. One, shown in the lower part of the figure, has a bulging frontal region similar to various cases we have already seen, while the two in the upper row appear to have nascent or ill-formed beaks. The beakless specimen was taken from the Danube near Pressburg (now Bratislava, the capital of Slovakia). Steindachner comments that "the fishermen there believe, so I am told, that these admittedly common monstrosities constitute a separate species" ("Die dortigen Fischer glauben, wie mir mitgetheilt wurde, dass diese ziemlich häufig vorkommenden Missgestalten einer eigenen Art angehören").

Three abnormal carp pictured in Steindachner (1863, Table 12).

Three abnormal carp pictured in Steindachner (1863, Table 12).

Are fish-bird hybrids possible?

A cross between a fish and a bird would be between separate vertebrate classes and so might seem impossible. But here we are dealing not with suppositions, but with the realities of nature, and, as Mark Twain once wrote, "Fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities. Truth isn’t." Given the reports on this page, it seems, at the very least, that the possible occurrence of fish-bird hybrids should be further investigated, and that, in particular, an effort should be made to gather all available knowledge on this topic in a single place. Moreover, the fact that there have been numerous serious reports about fish-mammal hybrids (fish-human hybrids, fish-cow hybrids, and fish-sheep hybrids)—all of which are crosses that, in taxonomic terms, are just as distant as one between a fish and a bird—tend also to support this view. Indeed, reports about a variety of other interclass crosses have been collected elsewhere on this website. So I, for my own part, plan to keep an open mind on this topic and to investigate it further.

Keywords for searching for further information on this topic: carpes à bec, carpes mopses, carpes dauphins, carpes à tête de dauphin, cyprinus rostratus,* cyprini rostrati, cyprini monstrosi rostrati, Mopskarpfen, or Delphinkarpfen. (Please contact the website with any new facts!)

By the same author: Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World, Oxford University Press (2006).

Incertae sedis

Another newspaper report also describes a creature with a body like that of a fish and a head like a bulldog's, but the type of fish is not indicated. Bulldog seems to be the name used in English to describe the same sort of fish described in German under the name Mops (meaning "pug dog") or in French as mopses. The following transcript is taken from the Chillicothe, Missouri, Crisis (Nov. 6, 1884, p. 1, col. 8):

Elmira lies on the western shore of Lake Erie.

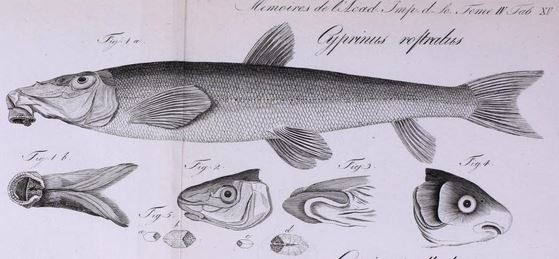

* The Latin word rostratus means having a beak, beaked, or curved, and cyprinus means carp. But rostrum means beak only in birds. In other animals it means snout, which results in ambiguity. Thus, the German naturalist Wilhelm Gottlieb Tilesius von Tilenau (1813, p. 454) uses the term Cyprinus rostratus to refer to what appear to be suckers (Family Catostomidae, Order Cypriniformes), which have a mouth quite different from a beak. See picture below.

Tilesius’s illustration of his Cyprinus rostratus (source: Tilesii 1813, Table 15)

Tilesius’s illustration of his Cyprinus rostratus (source: Tilesii 1813, Table 15)

Most shared on Macroevolution.net:

Human Origins: Are we hybrids?

On the Origins of New Forms of Life

Mammalian Hybrids

Cat-rabbit Hybrids: Fact or fiction?

Famous Biologists

Dog-cow Hybrids

Prothero: A Rebuttal

Branches of Biology

Dog-fox Hybrids

Conrad Gesner

Conrad Gesner