Cat-raccoon Hybrids

Mammalian Hybrids

|

And just to liven up the show, they had when I was there

A beast, alive, half cat half coon, and rattlesnakes a pair.

—Joseph Allen, The Old Log Jail†

|

Raccoons are about the same size as a domestic cat, though they are generally somewhat larger. Male raccoons, especially tame ones, will voluntarily mate with cats. But mating between wild coons and female cats also occurs.

Cats have also been known to nurse baby raccoons (see nursing video below). Under such circumstances, the baby coons would probably become imprinted on cats, so that they would be sexually attracted to cats when they reached maturity. (Imprinting is a widespread phenomenon in mammals and birds.)

So there is no absolute physical or behavioral barrier that separates the two. But the question of compatibility of their gametes remains. Is it possible for the insemination of a cat by a raccoon to result in the fertilization of a cat ovum by the sperm of a raccoon? And can any of the resulting zygotes develop into cat-raccoon hybrids? One can only answer such questions by surveying reports. In other words, the scientific approach is to investigate what has been observed and reported, and not to speculate about what might or might not be possible.

At present, there seem to be no efforts on the part of breeders to produce this cross, at least, none have reported it. However, older reports, mostly from the nineteenth century, suggest that it is in fact possible to produce cat-raccoon hybrids and that the Maine Coon breed of cat is derived from this cross. To confirm this conclusion, it will be necessary to replicate this cross under controlled conditions and/or carry out molecular genetic tests on putative hybrids. Until then, reports such as those quoted below constitute the only information available.

Cat-raccoon hybrids: Reports

There is at least one report about this cross that appeared in a scholarly publication. The American Naturalist is a monthly peer-reviewed scientific journal, published by the University of Chicago Press on behalf of the American Society of Naturalists. The October 1871 issue of that publication (vol. 5, no. 10, pp. 660-661) contains the following account authored by Thomas Wentworth Higginson (1823 – 1911), who is pictured at right.

She is larger than an average cat of that age, and is at once distinguishable both in shape and color. The color is a dark tawny, brindled with streaks that are almost black, on body and legs, and more obscurely on the tail. The under side of the body is lighter, as you will see from the matted hair which I enclose, and which was cut from the under side of one of the hind legs. (She is just now shedding her hair.) All the darker tints are quite unlike any that I ever saw in a cat. In shape she is somewhat slender, I should say though, this is concealed by the great length of the hair. The legs seem longer than a cat’s, and there is something peculiar in her gait as if they were set on differently. Her walk is neither plantigrade, nor yet quite feline, while it is easy and not ungraceful. I noticed no peculiarity in the paws, but the owner said she used them “unlike a cat more like a squirrel.” The head looks more triangular than a cat’s, possibly, from the pointed and tufted ears, which are quite peculiar. The expression of the creature’s face was so wild and formidable that I actually hesitated to touch her, but found her gentle and caressing, beyond even the habit of cats she seemed more sympathetic and human, instead of less so, which surprised me. But the chief beauty was in the hair, which I found to be very long and silken, with a softness such as I have rarely felt in any quadruped except at a very early age. This characteristic attains its greatest perfection in the tail which does not in the least remind one of a cat’s, but is as bushy and ornamental as a squirrel’s—broad and waving and graceful. I am not well acquainted with the raccoon, though I have seen it alive; but it seems a remarkable and interesting circumstance that a hybrid should have a softness and silkiness of coat beyond that of either progenitor.

A Maine Coon

A Maine Coon

The owner has had this beautiful animal but a few weeks and had the elder specimen of the same race but a day. He says that this one is ordinarily quite gentle and docile; but that on one occasion being taken up by the tail she turned upon the aggressor with a fury far beyond that of a common cat. She also never retreats before a dog, and the dog usually retires. She feeds on milk and meat, like a cat; but has never yet caught a mouse perhaps for want of opportunity. She is peculiarly nocturnal in her habits, is quite drowsy by day (which I also noticed), but becomes playful at night [raccoons are predominately nocturnal, unlike cats], and is always found rambling about the large shop in which she is confined.

Mr. Dunbar states that the other specimen of this breed, which he previously owned resembled this one in color and shape, but not in the length of hair, having more resemblance in that respect to the common cat. It would be exceedingly interesting to compare the different offspring of this strange union. I was unable to ascertain which of the parents—cat or raccoon—was the female; nor could I obtain the name of the person in China, Maine, beneath whose roof these singular hybrids were produced. Possibly you may have some correspondent in that locality who could give more accurate information. If it were possible to overcome, in this case, the ordinary infertility of hybrids. I am confident that there would be quite a demand for animals of this breed for their beauty alone.— T. W. Higginson, Newport, R. I.

On the next page (p. 662) of the same issue of the American Naturalist there is a letter to Higginson appended from John Whipple Potter Jenks, the director of Brown University’s Museum of Natural History:

Jenks

Jenks

Various news reports describe such hybrids and provide details about their ancestry and fertility. The following, which originated with the Albany, New York, Express, appeared in many newspapers around the country, but is here taken from the Wichita, Kansas, Daily Eagle (May 7, 1886, p. 5, col. 5; ||hlr97mg):

Giving Place to the Cat Craze

Since the fashion for lap dogs is fast giving place to the “pussy” craze, perhaps the society women of New York would like to know what a picturesque and curious species of the feline race we have up this way. The animal I refer to is the property of Mrs. Finley Hayes, of Greenbush [New York]. It is half raccoon and half Maltese [cat], and in appearance much resembles the coon, but the cat-like instincts are shown in her actions. The fur, which is a sort of a slate, reddish, brown and black in color, is long and bushy. The tail, unlike a cat’s, is wide and similar to that of a squirrel. The most curious characteristic is a natural fur collar about its neck, formed by the hair growing there much longer than on any part of the body. This unique animal is the mother of two kittens just toddling about and partaking largely of the peculiarities of the mother. It is said that Mrs. Hayes has had many large pecuniary offers for these very interesting offsprings, and for the mother the sum of $100 has been proffered. Albany Express

More information about hybridization of this kind appeared in a letter from biologist James Newton Baskett (1849-1925) entitled “Coon Cats” published in the Oct. 20, 1893 issue of the journal Science (vol. XXII, no. 559, p. 220): “Speaking of cats, I saw in a private house in Chicago recently, two cats which

—J[ames]. N[ewton]. Baskett, Mexico, Mo.*

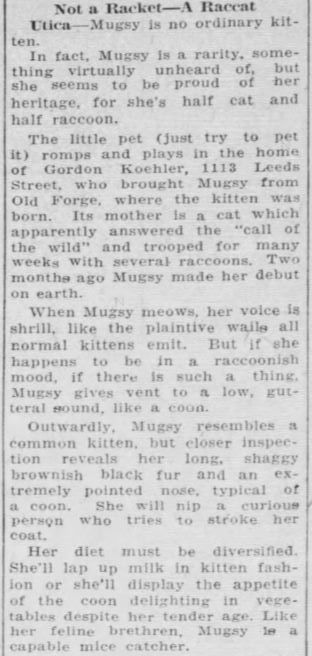

Above: A report about a cat-raccoon hybrid (Ithaca, New York, Journal, Oct. 10, 1933, p. 8, col. 4).

Above: A report about a cat-raccoon hybrid (Ithaca, New York, Journal, Oct. 10, 1933, p. 8, col. 4).

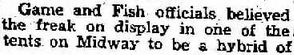

Above: A notice about a cat-raccoon hybrid (Huron, South Dakota, Evening Huronite, Sep. 7, 1939, p. 8).

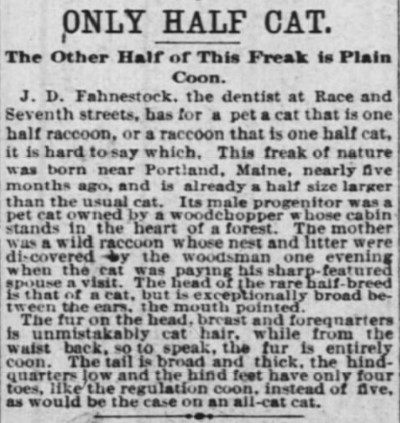

Above: A notice about a cat-raccoon hybrid (Huron, South Dakota, Evening Huronite, Sep. 7, 1939, p. 8). Above: A notice about a cat-raccoon hybrid born near Portland, Maine (Cincinnati Enquirer, Mar. 4, 1894, p. 16).

Above: A notice about a cat-raccoon hybrid born near Portland, Maine (Cincinnati Enquirer, Mar. 4, 1894, p. 16).

An additional point of interest is Wikipedia’s rejection of hybridization between cats and raccoons as an explanation of the Maine Coon’s origin. Thus, they say that one theory accounting for the origin of the breed,

|

which is trait-based, though genetically impossible, is the idea that the modern Maine Coon is descended from ancestors of semi-feral domestic cats and raccoons.‡ ‡. Wikipedia, "Maine Coon" (accessed 4/25/2015). |

But what is truly impossible is to know for sure in advance whether a given cross will produce hybrid offspring. Claims like Wikipedia's have often been made about crosses that turned out to be perfectly feasible once actually tried.

One example among many is the cross domestic pig x babirusa. Professional zookeepers, who were convinced that such a cross was impossible, placed a domestic pig together with a babirusa in a compound at the Copenhagen Zoo and were amazed when the pair produced perfectly viable hybrids. (At right are links to three articles about viable hybrids that conventional wisdom would describe as “impossible.”)

Claims that Maine coons are cat-raccoon hybrids abound in the older cat-breeding literature. For example, in the April 27, 1927 issue of the breeder’s periodical Cat Gossip (London, 1926-1932), the following is stated:

Such an account appears in the Saint Paul, Minnesota, Globe (Jan. 27, 1901, p. 23, col, 7):

MONEY RAISING CATS

The Famous Coon Cats of Maine

Bring as Much a $100

Saturday Evening Post.

The rearing of coon-cats is a coming industry. Coon cats are worth today from $5 to $100 apiece, and the supply does not begin to meet the demand. Exceptional specimens have been known to fetch $200 or even $300. At the present time all of them come from Maine, simply for the reason that the breed is peculiar as yet to that state. Their popularity is such that the business of breeding them has been rapidly growing during the last few years in that part of the country, and one shipper, not very far from Bar Harbor [Maine], exported in 1899 no fewer than 3,000 of the animals.

Strange to say, there are comparatively few people south or west of New England who know what a “coon-cat” is. If you ask that question “down in Maine,” however, the citizens will seem surprised at your ignorance, and will explain to you, in a condescending way, that the creature in question is half raccoon—the descendant of a “cross between a ’coon and a common cat.” Coon-cats have been recognized as a distinct breed in Maine for so long that the memory of the oldest inhabitant runs not back to their beginning. You will find several of them in almost any village in that part of the world.

Descriptions of Maine coons on the internet list raccoon-like traits of these cats, even while dismissing the idea of raccoon-cat hybrids as “impossible.” For example, a website about Maine coons states that “both raccoons and Maine coons have lush, long tails and the tendency to dunk their food into their drinking water.”

Raccoon chittering:

Another website states that “Maine Coon cats often talk with a chirpy trill, which is not dissimilar to the sound of a young raccoon.” Hybrids from many different types of crosses produce vocalizations that are a mix of sounds otherwise uttered only separately by their two parents. (Such is the case, for example, with hybrids between White-handed Gibbon and Pileated Gibbon, which produce calls that mix components of both their parents' calls.)

A third website says the

Raccoons and cats have identical chromosome counts, and similar karyotypes. Thus, Stanyon et al. (1993), after comparing the chromosomes of Felis catus with those of P. lotor, stated, “We propose a standardized karyotype for the raccoon (Procyon lotor; 2n = 38, FN 74) and compare it with that of the domestic cat (2n = 38, FN 72). Numerous chromosomes (12) have similar and sometimes identical G‐banding and 14 chromosome pairs have remained intact. Other chromosomes apparently differ by Robertsonian translocations and inversions. The conservation of these karyotypes is remarkable...”

Nevertheless, all too often, those unfamiliar with hybridization dismiss the possibility of a cross without empirical evaluation. The only unprejudiced way of resolving this issue in the present case is to mate a raccoon with a cat and then to see whether anything results (or to carry out artificial insemination). Genetic evaluation of existing Maine Coon cats in connection with this question might be difficult because, if they actually are of hybrid origin, they are probably the products of repeated backcrossing to cat. Later-generation backcrosses are difficult to detect via genetic techniques (Vähä and Primmer 2006, Engler et al. 2015).

More reports about cat-raccoon hybrids

A brief notice about a cat-raccoon hybrid appeared in the Lehi, Utah Banner (Dec. 27, 1906, p. 5):

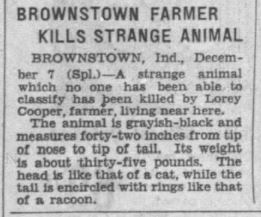

Another probable case was reported in the Indianapolis, Indiana, News (Dec. 7, 1934, p. 13, col. 3):

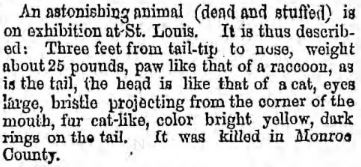

And the following notice, which appeared in the Brooklyn, New York, Daily Eagle (Apr. 5, 1870, p. 1, col. 8), obviously describes a cat-raccoon hybrid, if the report is true:

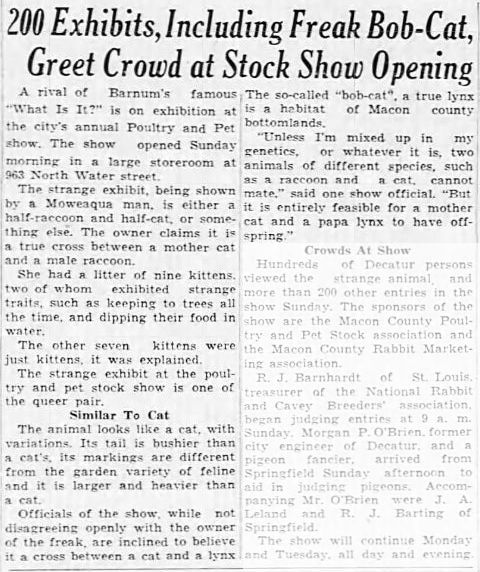

And the following report provides an example of how people—even those who have likely never experimented with or even read about hybrid crosses—are quite willing to make pronouncements about which sorts of hybrids are possible and which are not. It appeared in the Decatur, Illinois, Herald (Jan. 18, 1932, p. 3).

|  | |

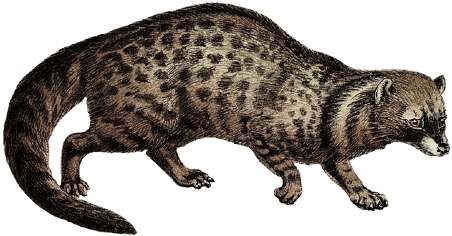

| An African Civet, shown at left, looks a lot like what one might expect in a cat-raccoon hybrid. But it isn't one. From just its face (right), it might be mistaken for a raccoon. | ||

† Source of epigraph: Nashville, Indiana, Brown County Democrat (Jun. 3, 1926, p. 1, ||y5em6cp5).

A list of cat crosses

The following is a list of reported cat crosses. Some of these crosses are much better documented than others (as indicated by the reliability arrow). Indeed, some might seem completely impossible. But all have been reported at least once. The links are to separate articles. Additional crosses, not listed here, are covered on the cat hybrids page.

|

|

Most shared on Macroevolution.net:

Human Origins: Are we hybrids?

On the Origins of New Forms of Life

Mammalian Hybrids

Cat-rabbit Hybrids: Fact or fiction?

Famous Biologists

Dog-cow Hybrids

Georges Cuvier: A Biography

Prothero: A Rebuttal

Branches of Biology

Dog-fox Hybrids

Cow-horse hybrids

Cow-horse hybrids Chicken-pigeon hybrids

Chicken-pigeon hybrids