Charles Darwin Biography

The Autobiography

Voyage of the Beagle

|

|

EUGENE M. MCCARTHY, PHD

| < | Famous Biologists | > |

CHARLES DARWIN'S AUTOBIOGRAPHY: Voyage of the Beagle from Dec. 27, 1831, to Oct. 2, 1836.

|

|

Contents:

|

On returning home from my short geological tour in North Wales, I found a letter from Henslow, informing me that Captain Fitz-Roy was willing to give up part of his own cabin to any young man who would volunteer to go with him without pay as naturalist to the Voyage of the Beagle. I have given, as I believe, in my MS. Journal an account of all the circumstances which then occurred; I will here only say that I was instantly eager to accept the offer, but my father strongly objected, adding the words, fortunate for me, "If you can find any man of common sense who advises you to go I will give my consent." So I wrote that evening and refused the offer. On the next morning I went to Maer to be ready for September 1st, and, whilst out shooting, my uncle [Josiah Wedgwood II, Emma's father] sent for me, offering to drive me over to Shrewsbury and talk with my father, as my uncle thought it would be wise in me to accept the offer. My father always maintained that he was one of the most sensible men in the world, and he at once consented in the kindest manner. I had been rather extravagant at Cambridge, and to console my father, said, "that I should be deuced clever to spend more than my allowance whilst on board the Beagle;" but he answered with a smile, "But they tell me you are very clever."

|

|

Josiah Wedgwood II (1769-1843) |

|

|

Robert Fitz-Roy (1805–1865) |

|

| Charles Darwin as a young man |

Next day I started for Cambridge to see Henslow, and thence to London to see Fitz-Roy, and all was soon arranged. Afterwards, on becoming very intimate with Fitz-Roy, I heard that I had run a very narrow risk of being rejected, on account of the shape of my nose! He was an ardent disciple of Lavater, and was convinced that he could judge of a man's character by the outline of his features; and he doubted whether any one with my nose could possess sufficient energy and determination for the voyage. But I think he was afterwards well satisfied that my nose had spoken falsely.

Fitz-Roy's character was a singular one, with very many noble features: he was devoted to his duty, generous to a fault, bold, determined, and indomitably energetic, and an ardent friend to all under his sway. He would undertake any sort of trouble to assist those whom he thought deserved assistance. He was a handsome man, strikingly like a gentleman, with highly courteous manners, which resembled those of his maternal uncle, the famous Lord Castlereagh, as I was told by the Minister at Rio. Nevertheless he must have inherited much in his appearance from Charles II., for Dr. Wallich gave me a collection of photographs which he had made, and I was struck with the resemblance of one to Fitz-Roy; and on looking at the name, I found it Ch. E. Sobieski Stuart, Count d'Albanie, a descendant of the same monarch ["Charles Edward Sobieski Stuart" was a name used by Charles Manning Allen, who, with his brother, perpetrated a fraud purporting them to be the descendants of the royal House of Stuart. They also used the fake name "Count d'Albanie." Darwin, writing in this autobiography in 1876, was apparently one of those still taken in by their ruse, although it had been thoroughly exposed long before.].

Fitz-Roy's temper was a most unfortunate one. It was usually worst in the early morning, and with his eagle eye he could generally detect something amiss about the ship, and was then unsparing in his blame. He was very kind to me, but was a man very difficult to live with on the intimate terms which necessarily followed from our messing by ourselves in the same cabin. We had several quarrels; for instance, early in the voyage at Bahia, in Brazil, he defended and praised slavery, which I abominated, and told me that he had just visited a great slave-owner, who had called up many of his slaves and asked them whether they were happy, and whether they wished to be free, and all answered "No." I then asked him, perhaps with a sneer, whether he thought that the answer of slaves in the presence of their master was worth anything? This made him excessively angry, and he said that as I doubted his word we could not live any longer together. I thought that I should have been compelled to leave the ship; but as soon as the news spread, which it did quickly, as the captain sent for the first lieutenant to assuage his anger by abusing me, I was deeply gratified by receiving an invitation from all the gun-room officers to mess with them. But after a few hours Fitz-Roy showed his usual magnanimity by sending an officer to me with an apology and a respect that I would continue to live with him.

His character was in several respects one of the most noble which I have ever known.

|

|

Voyage of the Beagle. Map: Kipala |

|

|

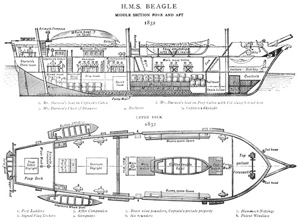

Plan of the Beagle |

|

| Model of the Beagle (Museum of Zoology, Saint Petersburg) |

The voyage of the Beagle has been by far the most important event in my life, and has determined my whole career; yet it depended on so small a circumstance as my uncle offering to drive me thirty miles to Shrewsbury, which few uncles would have done, and on such a trifle as the shape of my nose. I have always felt that I owe to the voyage the first real training or education of my mind; I was led to attend closely to several branches of natural history, and thus my powers of observation were improved, though they were always fairly developed.

The investigation of the geology of all the places visited was far more important, as reasoning here comes into play. On first examining a new district nothing can appear more hopeless than the chaos of rocks; but by recording the stratification and nature of the rocks and fossils at many points, always reasoning and predicting what will be found elsewhere, light soon begins to dawn on the district, and the structure of the whole becomes more or less intelligible. I had brought with me the first volume of Lyell's 'Principles of Geology,' which I studied attentively; and the book was of the highest service to me in many ways. The very first place which I examined, namely St. Jago in the Cape de Verde islands, showed me clearly the wonderful superiority of Lyell's manner of treating geology, compared with that of any other author, whose works I had with me or ever afterwards read.

|

|

Landscape, Santiago, Cape Verde Islands |

|

|

Ruins at Ribeira Grande, Santiago

Credit: Otimarte |

|

|

Nossa Senhora do Rosário, Ribeira Grande, the

oldest Portuguese colonial church in the world. Built 1495. Visited by Darwin. |

|

| Rocky shoreline, Santiago |

Another of my occupations was collecting animals of all classes, briefly describing and roughly dissecting many of the marine ones; but from not being able to draw, and from not having sufficient anatomical knowledge, a great pile of MS. which I made during the voyage has proved almost useless. I thus lost much time, with the exception of that spent in acquiring some knowledge of the Crustaceans, as this was of service when in after years I undertook a monograph of the Cirripedia.

During some part of the day I wrote my Journal, and took much pains in describing carefully and vividly all that I had seen; and this was good practice. My Journal served also, in part, as letters to my home, and portions were sent to England whenever there was an opportunity.

The above various special studies were, however, of no importance compared with the habit of energetic industry and of concentrated attention to whatever I was engaged in, which I then acquired. Everything about which I thought or read was made to bear directly on what I had seen or was likely to see; and this habit of mind was continued during the five years of the voyage. I feel sure that it was this training which has enabled me to do whatever I have done in science.

|

Contents:

|

Looking backwards, I can now perceive how my love for science gradually preponderated over every other taste. During the first two years my old passion for shooting survived in nearly full force, and I shot myself all the birds and animals for my collection; but gradually I gave up my gun more and more, and finally altogether, to my servant, as shooting interfered with my work, more especially with making out the geological structure of a country. I discovered, though unconsciously and insensibly, that the pleasure of observing and reasoning was a much higher one than that of skill and sport. That my mind became developed through my pursuits during the voyage is rendered probably by a remark made by my father, who was the most acute observer whom I ever saw, of a sceptical disposition, and far from being a believer in phrenology; for on first seeing me after the voyage, he turned round to my sisters, and exclaimed, "Why, the shape of his head is quite altered."

To return to the voyage. On September 11th (1831), I paid a flying visit with Fitz-Roy to the Beagle at Plymouth [in the western part of England's southern coast]. Thence to Shrewsbury to wish my father and sisters a long farewell. On October 24th I took up my residence at Plymouth, and remained there until December 27th, when the Beagle finally left the shores of England for her circumnavigation of the world. We made two earlier attempts to sail, but were driven back each time by heavy gales. These two months at Plymouth were the most miserable which I ever spent, though I exerted myself in various ways. I was out of spirits at the thought of leaving all my family and friends for so long a time, and the weather seemed to me inexpressibly gloomy. I was also troubled with palpitation and pain about the heart, and like many a young ignorant man, especially one with a smattering of medical knowledge, was convinced that I had heart disease. I did not consult any doctor, as I fully expected to hear the verdict that I was not fit for the voyage, and I was resolved to go at all hazards.

|

| The Beagle in Tierra del Fuego |

I need not here refer to the events of the voyage—where we went and what we did—as I have given a sufficiently full account in my published Journal. The glories of the vegetation of the Tropics rise before my mind at the present time more vividly than anything else; though the sense of sublimity, which the great deserts of Patagonia and the forest-clad mountains of Tierra del Fuego excited in me, has left an indelible impression on my mind. The sight of a naked savage in his native land is an event which can never be forgotten. Many of my excursions on horseback through wild countries, or in the boats, some of which lasted several weeks, were deeply interesting: their discomfort and some degree of danger were at that time hardly a drawback, and none at all afterwards. I also reflect with high satisfaction on some of my scientific work, such as solving the problem of coral islands, and making out the geological structure of certain islands, for instance, St. Helena. Nor must I pass over the discovery of the singular relations of the animals and plants inhabiting the several islands of the Galapagos archipelago, and of all of them to the inhabitants of South America.

As far as I can judge of myself, I worked to the utmost during the voyage from the mere pleasure of investigation, and from my strong desire to add a few facts to the great mass of facts in Natural Science. But I was also ambitious to take a fair place among scientific men,—whether more ambitious or less so than most of my fellow-workers, I can form no opinion.

The geology of St. Jago is very striking, yet simple: a stream of lava formerly flowed over the bed of the sea, formed of triturated recent shells and corals, which it has baked into a hard white rock. Since then the whole island has been upheaved. But the line of white rock revealed to me a new and important fact, namely, that there had been afterwards subsidence round the craters, which had since been in action, and had poured forth lava. It then first dawned on me that I might perhaps write a book on the geology of the various countries visited, and this made me thrill with delight. That was a memorable hour to me, and how distinctly I can call to mind the low cliff of lava beneath which I rested, with the sun glaring hot, a few strange desert plants growing near, and with living corals in the tidal pools at my feet. Later in the voyage, Fitz-Roy asked me to read some of my Journal, and declared it would be worth publishing; so here was a second book in prospect!

[The following is material taken from Darwin's Beagle journal, beginning with his description of his explorations of St. Jago (modern Santiago, in the Cape Verde Islands), the Beagle's first landfall after leaving England]

|

|

Location of the Cape Verde Islands Map: Rei-artur |

|

| Grey-headed kingfisher, Halcyon leucocephala |

JAN. 16TH, 1832.—The neighbourhood of Porto Praya, viewed from the sea, wears a desolate aspect. The volcanic fire of past ages, and the scorching heat of a tropical sun, have in most places rendered the soil sterile and unfit for vegetation. The country rises in successive steps of table land, interspersed with some truncate conical hills, and the horizon is bounded by an irregular chain of more lofty mountains. The scene, as beheld through the hazy atmosphere of this climate, is one of great interest; if, indeed, a person, fresh from the sea, and who has just walked, for the first time, in a grove of cocoa-nut trees, can be a judge of any thing but his own happiness. The island would generally be considered as very uninteresting; but to any one accustomed only to an English landscape, the novel prospect of an utterly sterile land possesses a grandeur which more vegetation might spoil. A single green leaf can scarcely be discovered over wide tracts of the lava plains; yet flocks of goats, together with a few cows, contrive to exist. It rains very seldom, but during a short portion of the year heavy torrents fall, and immediately afterwards a light vegetation springs out of every crevice. This soon withers; and upon such naturally-formed hay the animals live. At the present time it has not rained for an entire year. The broad, flat-bottomed, valleys, many of which serve during a few days only in the season as a watercourse, are clothed with thickets of leafless bushes. Few living creatures inhabit these valleys. The commonest bird is a kingfisher (Dacelo jagoensis [presumably the same bird that now goes by the name Grey-headed Kingfisher Halcyon leucocephala, the only kingfisher that regularly occurs in the Cape Verdes, see figure right]), which tamely sits on the branches of the castor-oil plant, and thence darts on the grasshoppers and lizards. It is brightly coloured, but not so beautiful as the European species: in its flight, manners, and place of habitation, which is generally in the driest valleys, there is also a wide difference.

|

| Map of Santiago, Cape Verde Islands, showing sites visited by Darwin |

One day, two of the officers and myself rode to Ribeira Grande, a village a few miles to the eastward of Porto Praya. Until we reached the valley of St. Martin, the country presented its usual dull brown appearance; but there, a very small rill of water produces a most refreshing margin of luxuriant vegetation. In the course of an hour we arrived at Ribeira Grande, and were surprised at the sight of a large ruined fort and cathedral. The little town, before its harbour was filled up, was the principal place in the island: it now presents a melancholy, but very picturesque appearance. Having procured a black Padre for a guide, and a Spaniard, who had served in the Peninsular war, as an interpreter, we visited a collection of buildings, of which an ancient church formed the principal part. It is here the governors and captain-generals of the islands have been buried. Some of the tombstones recorded dates of the sixteenth century [the Cape Verde Islands were discovered around 1460].

The heraldic ornaments were the only things in this retired place that reminded us of Europe. The church or chapel formed one side of a quadrangle, in the middle of which a large clump of bananas were growing. On another side was a hospital, containing about a dozen miserable-looking inmates.

We returned to the "Vênda" [Portuguese for inn] to eat our dinners. A considerable number of men, women, and children, all as black as jet, were collected to watch us. Our companions were extremely merry; and every thing we said or did was followed by their hearty laughter. Before leaving the town we visited the cathedral. It does not appear so rich as the smaller church, but boasts of a little organ, which sent forth most singularly inharmonious cries. We presented the black priest with a few shillings, and the Spaniard, patting him on the head, said, with much candour, he thought his colour made no great difference. We then returned, as fast as the ponies would go, to Porto Praya.

Another day we rode to the village of St. Domingo, situated near the centre of the island. On a small plain which we crossed, a few stunted acacias were growing; their tops, by the action of the steady trade-wind, were bent in a singular manner—some of them even at a right angle to the trunk. The direction of the branches was exactly N.E. by N., and S.W. by S. These natural vanes must indicate the prevailing direction of the force of the trade wind. The travelling had made so little impression on the barren soil, that we here missed our track, and took that to Fuentes. This we did not find out till we arrived there; and we were afterwards very glad of our mistake. Fuentes is a pretty village, with a small stream; and every thing appeared to prosper well, excepting, indeed, that which ought to do so most—its inhabitants. The black children, completely naked, and looking very wretched, were carrying bundles of firewood half as big as their own bodies.

Near Fuentes we saw a large flock of guinea-fowl — probably fifty or sixty in number. They were extremely wary, and could not be approached. They avoided us, like partridges on a rainy day in September, running with their heads cocked up; and if pursued, they readily took to the wing.

|

Contents:

|

The scenery of St. Domingo possesses a beauty totally unexpected, from the prevalent gloomy character of the rest of the island. The village is situated at the bottom of a valley, bounded by lofty and jagged walls of stratified lava. The black rocks afford a most striking contrast with the bright green vegetation, which follows the banks of a little stream of clear water. It happened to be a grand feast-day, and the village was full of people. On our return we overtook a party of about twenty young black girls, dressed in most excellent taste; their black skins and snow-white linen being set off by their coloured turbans and large shawls. As soon as we approached near, they suddenly all turned round, and covering the path with their shawls, sung with great energy a wild song, beating time with their hands upon their legs. We threw them some vintéms, which were received with screams of laughter, and we left them redoubling the noise of their song.

…

|

|

Aplysia californica Photo: Nordelch |

|

| Portuguese man-of-war |

During our stay, I observed the habits of some marine animals. A large Aplysia is very common. This sea-slug is about five inches long; and is of a dirty yellowish colour, veined with purple. At the anterior extremity, it has two pair of feelers; the upper ones of which resemble in shape the ears of a quadruped. On each side of the lower surface, or foot, there is a broad membrane, which appears sometimes to act as a ventilator, in causing a current of water to flow over the dorsal branchiæ. It feeds on delicate sea-weeds, which grow among the stones in muddy and shallow water; and I found in its stomach several small pebbles, as in the gizzards of birds. This slug, when disturbed, emits a very fine purplish-red fluid, which stains the water for the space of a foot around. Besides this means of defence, an acrid secretion, which is spread over its body, causes a sharp, stinging sensation, similar to that produced by the Physalia, or Portuguese man-of-war.

|

| Cuttlefish camouflage: (1) Disguised animal; (2) same animal undisguised (click to enlarge) Photo: Nick Hobgood |

I was much interested, on several occasions, by watching the habits of an octopus or cuttle-fish. Although common in the pools of water left by the retiring tide, these animals were not easily caught. By means of their long arms and suckers, they could drag their bodies into very narrow crevices; and when thus fixed, it required great force to remove them. At other times they darted tail first, with the rapidity of an arrow, from one side of the pool to the other, at the same instant discolouring the water with a dark chestnut-brown ink. These animals also escape detection by a very extraordinary, chameleon-like, power of changing their colour. They appear to vary the tints, according to the nature of the ground over which they pass: when in deep water, their general shade was brownish purple, but when placed on the land, or in shallow water, this dark tint changed into one of a yellowish green. The colour, examined more carefully, was a French gray, with numerous minute spots of bright yellow: the former of these varied in intensity; the latter entirely disappeared and appeared again by turns. These changes were effected in such a manner, that clouds, varying in tint between a hyacinth red and a chestnut brown, were continually passing over the body. Any part being subjected to a slight shock of galvanism, became almost black: a similar effect, but in a less degree, was produced by scratching the skin with a needle. These clouds, or blushes, as they may be called, when examined under a glass, are described as being produced by the alternate expansions and contractions of minute vesicles, containing variously-coloured fluids.

|

Contents:

|

This cuttle-fish displayed its chameleon-like power both during the act of swimming and whilst remaining stationary at the bottom. I was much amused by the various arts to escape detection used by one individual, which seemed fully aware that I was watching it. Remaining for a time motionless, it would then stealthily advance an inch or two, like a cat after a mouse; sometimes changing its colour: it thus proceeded, till having gained a deeper part, it darted away, leaving a dusky train of ink to hide the hole into which it had crawled.

While looking for marine animals, with my head about two feet above the rocky shore, I was more than once saluted by a jet of water, accompanied by a slight grating noise. At first I did not know what it was, but afterwards I found out that it was the cuttle-fish, which, though concealed in a hole, thus often led me to its discovery. That it possesses the power of ejecting water there is no doubt, and it appeared to me certain that it could, moreover, take good aim by directing the tube or siphon on the under side of its body. From the difficulty which these animals have in carrying their heads, they cannot crawl with ease when placed on the ground. I observed that one which I kept in the cabin was slightly phosphorescent in the dark.

|

|

St. Paul's Rocks |

|

| Location of St. Paul's Rocks |

ST. PAUL'S ROCKS.—In crossing the Atlantic we hove to, during the morning of February 16th [1832], close to the island of St. Paul. This cluster of rocks is situated in 0° 58' north latitude, and 29° 15' west longitude. It is 540 miles distant from the coast of America, and 350 from the island of Fernando Noronha. The highest point is only fifty feet above the level of the sea, and the entire circumference is under three-quarters of a mile. This small point rises abruptly out of the depths of the ocean. Its mineralogical constitution is not simple; in some parts, the rock is of a cherty, in others, of a felspathic nature; and in the latter case it contains thin veins of serpentine, mingled with calcareous matter.

…

The rocks of St. Paul appear from a distance of a brilliantly white colour. This is partly owing to the dung of a vast multitude of seafowl, and partly to a coating of a glossy white substance, which is intimately united to the surface of the rocks. … It consists of phosphate of lime, mingled with some impurities; and its origin without doubt is due to the action of the rain or spray on the bird's dung. I may here mention, that I found in some hollows in the lava rocks of Ascension considerable masses of the substance called guano, which on the west coast of the intertropical parts of South America occurs in great beds, some yards thick, on the islets frequented by seafowl. … I believe there is no doubt of its being the richest manure which has ever been discovered. …

| |

| Brown booby, Sula leucogaster | |

|

|

|

Quedius | Feronia |

We only observed two kinds of birds—the booby and the noddy. The former is a species of gannet, and the latter a tern [Modern surveys have shown the rocks are inhabited by the Brown Booby (Sula leucogaster), Brown Noddy (Anous stolidus), and Black Noddy (Anous minutus)]. Both are of a tame and stupid disposition, and are so unaccustomed to visitors, that I could have killed any number of them with my geological hammer. The booby lays her eggs on the bare rock; but the tern makes a very simple nest with sea-weed. By the side of many of these nests a small flying-fish was placed; which, I suppose, had been brought by the male bird for its partner. It was amusing to watch how quickly a large and active crab (Graspus [sic, presumably, Grapsus adscensionis], which inhabits the crevices of the rock, stole the fish from the side of the nest, as soon as we had disturbed the birds. Not a single plant, not even a lichen, grows on this island; yet it is inhabited by several insects and spiders. The following list completes, I believe, the terrestrial fauna: a species of Feronia and an acarus, which must have come here as parasites on the birds; a small brown moth, belonging to a genus that feeds on feathers; a staphylinus (Quedius) and a woodlouse from beneath the dung; and lastly, numerous spiders, which I suppose prey on these small attendants on, and scavengers of the waterfowl. The often-repeated description of the first colonists of the coral islets in the South Sea, is not, probably, quite correct: I fear it destroys the poetry of the story to find, that these little vile insects should thus take possession before the cocoa-nut tree and other noble plants have appeared.

…

BAHIA, OR SAN SALVADOR. BRAZIL, FEB. 29TH. — The day has past delightfully. Delight itself, however, is a weak term to express the feelings of a naturalist who, for the first time, has been wandering by himself in a Brazilian forest. Among the multitude of striking objects, the general luxuriance of the vegetation bears away the victory. The elegance of the grasses, the novelty of the parasitical plants, the beauty of the flowers, the glossy green of the foliage, all tend to this end. A most paradoxical mixture of sound and silence pervades the shady parts of the wood. The noise from the insects is so loud, that it may be heard even in a vessel anchored several hundred yards from the shore; yet within the recesses of the forest a universal silence appears to reign. To a person fond of natural history, such a day as this, brings with it a deeper pleasure than he ever can hope again to experience. After wandering about for some hours, I returned to the landing-place; but, before reaching it, I was overtaken by a tropical storm. I tried to find shelter under a tree which was so thick, that it would never have been penetrated by common English rain; but here, in a couple of minutes, a little torrent flowed down the trunk. It is to this violence of the rain we must attribute the verdure at the bottom of the thickest woods: if the showers were like those of a colder clime, the greater part would be absorbed or evaporated before it reached the ground. I will not at present attempt to describe the gaudy scenery of this noble bay, because, in our homeward voyage, we called here a second time, and I shall then have occasion to remark on it.

|

|

Diodon Photo: Ibrahim Iujaz |

One day I was amused by watching the habits of a Diodon, which was caught swimming near the shore. This fish is well known to possess the singular power of distending itself into a nearly spherical form. After having been taken out of water for a short time, and then again immersed in it, a considerable quantity both of water and air was absorbed by the mouth, and perhaps likewise by the branchial apertures. This process is effected by two methods; the air is swallowed, and is then forced into the cavity of the body, its return being prevented by a muscular contraction which is externally visible; but the water, I observed, entered in a stream through the mouth, which was wide open and motionless: this latter action must, therefore, depend on suction. The skin about the abdomen is much looser than that of the back; hence, during the inflation, the lower surface becomes far more distended than the upper; and the fish, in consequence, floats with its back downwards. Cuvier doubts whether the Diodon, in this position, is able to swim; but not only can it thus move forward in a straight line, but likewise it can turn round to either side. This latter movement is effected solely by the aid of the pectoral fins; the tail being collapsed, and not used. From the body being buoyed up with so much air, the branchial openings were out of water; but a stream drawn in by the mouth, constantly flowed through them.

The fish, having remained in this distended state for a short time, generally expelled the air and water with considerable force from the branchial apertures and mouth. It could emit, at will, a certain portion of the water; and it appears, therefore, probable, that this fluid is taken in partly for the sake of regulating its specific gravity. This diodon possessed several means of defence. It could give a severe bite, and could eject water from its mouth to some distance, at the same time it made a curious noise by the movement of its jaws. By the inflation of its body, the papillæ, with which the skin is covered, became erect and pointed. But the most curious circumstance was, that it emitted from the skin of its belly, when handled, a most beautiful carmine red and fibrous secretion, which stained ivory and paper in so permanent a manner, that the tint is retained with all its brightness to the present day. I am quite ignorant of the nature and use of this secretion.

|

Contents:

|

RIO DE JANEIRO. APRIL 4TH TO JULY 5TH, 1832.—A few days after our arrival I became acquainted with an Englishman who was going to visit his estate situated, rather more than a hundred miles from the capital, to the northward of Cape Frio [Cabo Frio]. As I was quite unused to travelling, I gladly accepted his kind offer of allowing me to accompany him.

APRIL 8TH.—Our party amounted to seven. The first stage was very interesting. The day was powerfully hot, and as we passed through the woods, every thing was motionless, excepting the large and brilliant butterflies, which lazily fluttered about. The view seen when crossing the hills behind Praia Grande was most beautiful; the colours were intense, and the prevailing tint a dark blue; the sky and the calm waters of the bay vied with each other in splendour. After passing through some cultivated country, we entered a forest, which in the grandeur of all its parts could not be exceeded. We arrived by midday at Ithacaia; this small village is situated on a plain, and round the central house are the huts of the negroes. These, from their regular form and position, reminded me of the drawings of the Hottentot habitations in Southern Africa. As the moon rose early, we determined to start the same evening for our sleeping-place at the Lagoa Marica. As it was growing dark we passed under one of the massive, bare, and steep hills of granite which are so common in this country. This spot is notorious from having been, for a long time, the residence of some runaway slaves, who, by cultivating a little ground near the top, contrived to eke out a subsistence. At length they were discovered, and a party of soldiers being sent, the whole were seized with the exception of one old woman, who sooner than again be led into slavery, dashed herself to pieces from the summit of the mountain. In a Roman matron this would have been called the noble love of freedom: in a poor negress it is mere brutal obstinacy. We continued riding for some hours. For the few last miles the road was intricate, and it passed through a desert waste of marshes and lagoons. The scene by the dimmed light of the moon was most desolate. A few fireflies flitted by us; and the solitary snipe, as it rose, uttered its plaintive cry. The distant and sullen roar of the sea scarcely broke the stillness of the night.

APRIL 9TH.—We left our miserable sleeping-place before sunrise. The road passed through a narrow sandy plain, lying between the sea and the interior salt lagoons. The number of beautiful fishing birds, such as egrets and cranes, and the succulent plants assuming most fantastical forms, gave to the scene an interest which it would not otherwise have possessed. The few stunted trees were loaded with parasitical plants, among which the beauty and delicious fragrance of some of the orchideæ were most to be admired. As the sun rose, the day became extremely hot, and the reflection of the light and heat from the white sand was very distressing. We dined at Mandetiba; the thermometer in the shade being 84°. The beautiful view of the distant wooded hills, reflected in the perfectly calm water of an extensive lagoon, quite refreshed us. As the vênda [Portuguese for inn] here was a very good one, and I have the pleasant, but rare remembrance, of an excellent dinner, I will be grateful and presently describe it, as the type of its class. These houses are often large, and are built of thick upright posts, with boughs interwoven, and afterwards plastered. They seldom have floors, and never glazed windows; but are generally pretty well roofed. Universally the front part is open, forming a kind of verandah, in which tables and benches are placed. The bed-rooms join on each side, and here the passenger may sleep as comfortably as he can, on a wooden platform, covered by a thin straw mat. The vênda stands in a courtyard, where the horses are fed. On first arriving, it was our custom to unsaddle the horses and give them their Indian corn; then, with a low bow, to ask the senhôr to do us the favour to give us something to eat. "Any thing you choose, sir," was his usual answer. For the few first times, vainly I thanked Providence for having guided us to so good a man. The conversation proceeding, the case universally became deplorable. "Any fish can you do us the favour of giving?"—"Oh! no, sir."—"Any soup?"—"No, sir."—"Any bread ?"—"Oh ! no, sir."—"Any dried meat?"—"Oh! no, sir." If we were lucky, by waiting a couple of hours, we obtained fowls, rice, and farinha. It not unfrequently happened, that we were obliged to kill, with stones, the poultry for our own supper. When thoroughly exhausted by fatigue and hunger, we timorously hinted that we should be glad of our meal, the pompous, and (though true) most unsatisfactory answer was, "It will be ready when it is ready." If we had dared to remonstrate any further, we should have been told to proceed on our journey, as being too impertinent. The hosts are most ungracious and disagreeable in their manners; their houses and their persons are often filthily dirty; the want of the accommodation of forks, knives, and spoons is common; and I am sure no cottage or hovel in England could be found in a state so utterly destitute of every comfort. At Campos Novos, however, we fared sumptuously; having rice and fowls, biscuit, wine, and spirits, for dinner; coffee in the evening, and fish with coffee for breakfast. All this, with good food for the horses, only cost 2s. 6d. per head. Yet the host of this vênda, being asked if he knew any thing of a whip which one of the party had lost, gruffly answered, "How should I know? Why did you not take care of it?—I suppose the dogs have eat it."

|

|

Hydrophilus Water beetle |

Leaving Mandetiba, we continued to pass through an intricate wilderness of lakes; in some of which were fresh, in others salt water shells. Of the former kind I found a Limnæa in great numbers in a lake, into which, the inhabitants assured me, the sea annually, and sometimes oftener, entered, and made the water quite salt. I have no doubt many interesting facts, in relation to marine and fresh water animals, might be observed in this chain of lagoons, which skirt the coast of Brazil. M. Gay [Darwin cites Annales des Sciences Naturelles, 1833] has stated that he found in the neighbourhood of Rio, shells of the marine genera solen and mytilus, and fresh water ampullariæ, living together in brackish water. I also frequently observed in the lagoon near the Botanic Garden, where the water is only a little less salt than in the sea, a species of hydrophilus, very similar to a species common in the ditches of England: in the same lake the only shell belonged to a genus generally found in estuaries.

|

|

South American anthill Photo: Carlos Ponte |

|

|

Vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus) |

Leaving the coast for a time, we again entered the forest. The trees were very lofty, and remarkable, compared to those of Europe, from the whiteness of their trunks. I see by my note-book, "wonderful and beautiful, flowering parasites," invariably struck me as the most novel object in these grand scenes. Travelling onwards we passed through tracts of pasturage, much injured by the enormous conical ants' nests, which were nearly twelve feet high. They gave to the plain exactly the appearance of the mud volcanoes at Jorullo, as figured by Humboldt. We arrived at Engenhodo after it was dark, having been ten hours on horseback. I never ceased, during the whole journey, to be surprised at the amount of labour which the horses were capable of enduring; they appeared also to recover from any injury much sooner than those of our English breed. The Vampire bat is often the cause of much trouble, by biting the horses on their withers. The injury is generally not so much owing to the loss of blood, as to the inflammation which the pressure of the saddle afterwards produces. The whole circumstance has lately been doubted in England; I was therefore fortunate in being present when one was actually caught on a horse's back. We were bivouacking late one evening near Coquimbo, in Chile, when my servant, noticing that one of the horses was very restive, went to see what was the matter, and fancying he could distinguish something, suddenly put his hand on the beast's withers, and secured the vampire. In the morning, the spot, where the bite had been inflicted, was easily distinguished from being slightly swollen and bloody. The third day afterwards we rode the horse, without any ill effects.

APRIL 13TH.—After three days' travelling we arrived at Socêgo, the estate of Senhôr Manuel Figuireda, a relation of one of our party. The house was simple, and, though like a barn in form, was well suited to the climate. In the sitting-room gilded chairs and sofas were oddly contrasted with the whitewashed walls, thatched roof, and windows without glass. The house, together with the granaries, the stables, and workshops for the blacks, who had been taught various trades, formed a rude kind of quadrangle; in the centre of which a large pile of coffee was drying. These buildings stand on a little hill, overlooking the cultivated ground, and surrounded on every side by a wall of dark green luxuriant forest. The chief produce of this part of the country is coffee. Each tree is supposed to yield annually, on an average, two pounds; but some give as much as eight. Mandioca or cassada [manioc or cassava] is likewise cultivated in great quantity. Every part of this plant is useful: the leaves and stalks are eaten by the horses, and the roots are ground into a pulp, which, when pressed dry and baked, forms the farinha, the principal article of sustenance in the Brazils. It is a curious, though well-known fact, that the expressed juice of this most nutritious plant is highly poisonous. A few years ago a cow died at this Fazênda, in consequence of having drunk some of it. Senhôr Figuireda told me that he had planted, the year before, one bag of feijaô or beans, and three of rice; the former of which produced eighty, and the latter three hundred and twenty fold. The pasturage supports a fine stock of cattle, and the woods are so full of game, that a deer had been killed on each of the three previous days. This profusion of food showed itself at dinner, where, if the tables did not groan, the guests surely did: for each person is expected to eat of every dish. One day, having, as I thought, nicely calculated so that nothing should go away untasted, to my utter dismay a roast turkey and a pig appeared in all their substantial reality. During the meals, it was the employment of a man to drive out of the room sundry old hounds, and dozens of little black children, which crawled in together, at every opportunity. As long as the idea of slavery could be banished, there was something exceedingly fascinating in this simple and patriarchal style of living: it was such a perfect retirement and independence of the rest of the world. As soon as any stranger is seen arriving, a large bell is set tolling, and generally some small cannon are fired. The event is thus announced to the rocks and woods, but to nothing else. One morning I walked out an hour before daylight to admire the solemn stillness of the scene; at last, the silence was broken by the morning hymn, raised on high by the whole body of the blacks; and in this manner, their daily work is generally begun. On such fazendas as these, I have no doubt the slaves pass happy and contented lives. On Saturday and Sunday they work for themselves, and in this fertile climate the labour of two days is sufficient to support a man and his family for the whole week.

[Note: Material from Darwin's Beagle Journal will be added at this point to create a continuous narrative.]

|

|

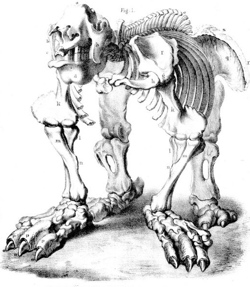

Skeleton of giant ground sloth Megatherium found

by Darwin at Bahia Blanca, Argentina. |

|

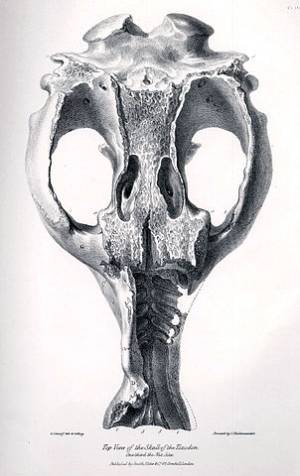

| Skull of a Toxodon found by Darwin in Argentina. |

Towards the close of our voyage I received a letter whilst at Ascension [Island], in which my sisters told me that Sedgwick had called on my father, and said that I should take a place among the leading scientific men. I could not at the time understand how he could have learnt anything of my proceedings, but I heard (I believe afterwards) that Henslow had read some of the letters which I wrote to him before the Philosophical Society of Cambridge, and had printed them for private distribution. My collection of fossil bones, which had been sent to Henslow, also excited considerable attention amongst palæontologists. After reading this letter, I clambered over the mountains of Ascension with a bounding step, and made the volcanic rocks resound under my geological hammer. All this shows how ambitious I was; but I think that I can say with truth that in after years, though I cared in the highest degree for the approbation of such men as [Sir Charles] Lyell and [Sir Joseph Dalton] Hooker, who were my friends, I did not care much about the general public. I do not mean to say that a favourable review or a large sale of my books did not please me greatly, but the pleasure was a fleeting one, and I am sure that I have never turned one inch out of my course to gain fame.

Most shared on Macroevolution.net:

Human Origins: Are we hybrids?

On the Origins of New Forms of Life

Mammalian Hybrids

Cat-rabbit Hybrids: Fact or fiction?

Famous Biologists

Dog-cow Hybrids

Georges Cuvier: A Biography

Prothero: A Rebuttal

Branches of Biology

Dog-fox Hybrids