Conjoined Twins

|

We call contrary to Nature what happens contrary to what is customary; there is nothing whatsoever that is contrary to Nature.

—Michel de Montaigne

|

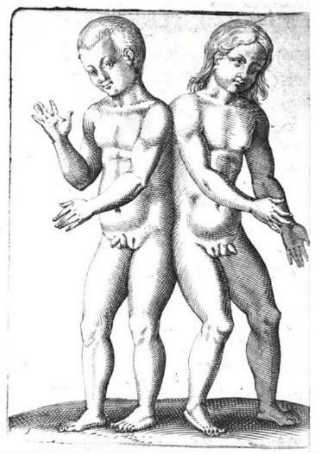

Hermaphroditic conjoined twins, an almost unheard of rarity (source: Bauhin, De Hermaphroditorum, 1614).

Hermaphroditic conjoined twins, an almost unheard of rarity (source: Bauhin, De Hermaphroditorum, 1614).

Conjoined twins are twins that develop from the same zygote but that only partially separate during the course of development. The incidence of this condition is estimated to be less than 2 births in 100,000. A famous modern example is the case of Abigail and Brittany Hensel, the American conjoined twins with two heads and one body (see video below). The condition of having more than one head is known as polycephaly. There are also cases in which two bodies are attached to a single head. In polydactylism extra fingers or toes are present, in polymelia, extra arms or legs.

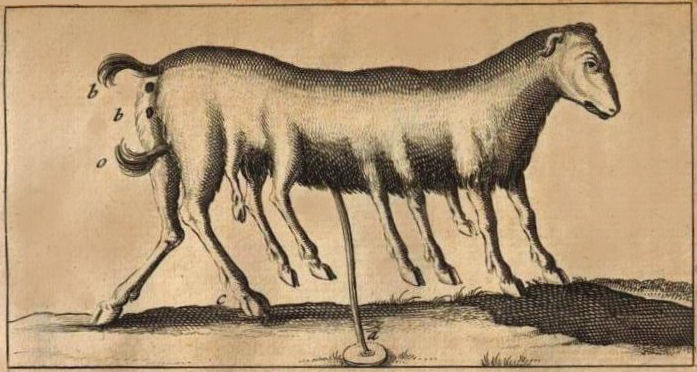

Conjoined triplets, though far rarer, also occur (example). Liceti cites a case of this in a sheep (see image below). A calf with three heads was born at Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin in 1922 (link). Human conjoined triplets, too, are known. For example, a baby with three heads was born in Virginia in 1866. In St. Louis, Missouri, in 1896, a cat gave birth to conjoined quintuplets.

Article continues below

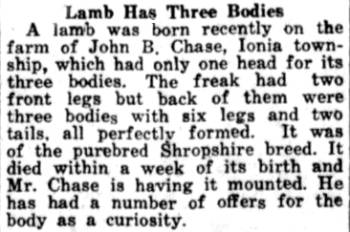

Old news notice (source) about a conjoined triplet sheep with three bodies and one head, instead of three heads and one body, as pictured by Liceti. Schultze (1640, pp. 184-185) records an additional, early case of a conjoined triplet lamb with a single head. And there was a similar case involving a pig.

Old news notice (source) about a conjoined triplet sheep with three bodies and one head, instead of three heads and one body, as pictured by Liceti. Schultze (1640, pp. 184-185) records an additional, early case of a conjoined triplet lamb with a single head. And there was a similar case involving a pig.

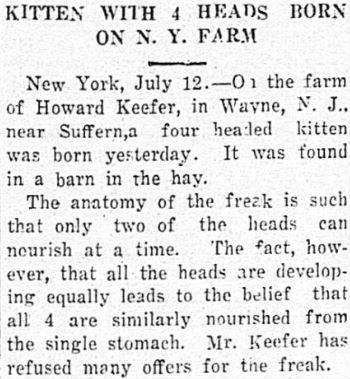

Old news article (source) about a kitten with four heads, born in New York in 1921. An old California newspaper article describes a calf with three heads, each containing a single cyclopian eye.

Old news article (source) about a kitten with four heads, born in New York in 1921. An old California newspaper article describes a calf with three heads, each containing a single cyclopian eye.Another four-headed cat >>

A seven-headed kitten >>

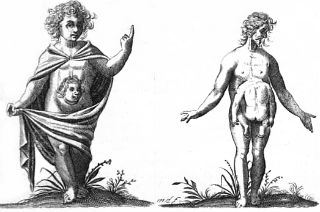

Parasitic twins. Left: A parasitic head without a body; right: A parasitic body without a head (source: Liceti 1634, p. 99).

Parasitic twins. Left: A parasitic head without a body; right: A parasitic body without a head (source: Liceti 1634, p. 99).

Man with a parasitic twin composed of a body without a head (source: Schenk, 1609).

Man with a parasitic twin composed of a body without a head (source: Schenk, 1609).

Parasitic Twins

A parasitic twin (also known as an asymmetrical or unequal conjoined twin) is the result of the same processes that produce ordinary conjoined twins, except that one of the two twins (the autosite) develops more completely than the other (the parasite). The condition has long been recognized. For example, the illustration at right dates to the 17th century (view photos of a similar modern case >>). The parasite can be attached to various regions of the autosite’s body. For example, in 2005 a woman in Egypt gave birth to conjoined twins in which the parasite was merely a head attached to the upper left portion of the autosite’s head (see video below), a rare condition known as craniopagus parasiticus. An 18th century instance of the same syndrome, the Two-headed Boy of Bengal, is pictured below.

The Two-headed Boy of Bengal, conjoined twins in which one twin was a parasitic head (craniopagus parasiticus).

The Two-headed Boy of Bengal, conjoined twins in which one twin was a parasitic head (craniopagus parasiticus).A contemporary case of craniopagus parasiticus.

Hybrid conjoined twins

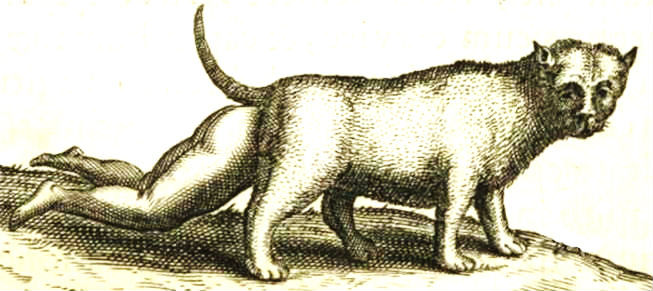

In addition, there are various reports about hybrid conjoined twins, both equal and parasitic, the latter being considerably more common. Most hybrid conjoined twins seem to involve rather distant crosses. Thus, the Italian scholar Fortunio Liceti pictures what he claims was a cat with a human buttocks and legs hanging from its posterior, born to a woman at Padua in 1629, a cat with an exterogenetic parasitic human attachment.

A purported cat-human hybrid, which would also represent a case of unequal conjoined twins (pictured in Liceti 1634). Enlarge

A purported cat-human hybrid, which would also represent a case of unequal conjoined twins (pictured in Liceti 1634). Enlarge

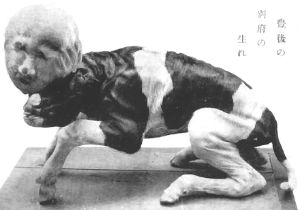

Liceti’s cat-human is by no means the only such birth reported. Thus, there are at least three separate cases of ostensible human-cow hybrids with the head, body, and legs of a cow, but with an additional human-like head attached atop the cow head (learn more about these cases here). The Japanese case is pictured below, but there was also one reported in Paris, and one in Ohio, here in the United States.

Enlarge

EnlargeCalf with an exterogenetic parasitic human attachment.

Another report about a bovine animal with an exterogenetic parasitic human attachment, this time a human arm with hand, appeared in many American newspapers in 1874. The material quoted here was taken from the Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania, Jeffersonian (Nov. 26, 1874, p. 1 , col. 5):

A Sacred Bull That has an Arm Like a Man

This case, in which a human arm was attached to the back of a bull, parallels another case, an ostensible deer-cow hybrid, a male animal that looked like a bull with the muzzle and pelt of a deer, and that had in the middle of his back a well-formed deer leg, which was attached to a deerlike male member about a foot long, including two testicles. Another case of an ostensible cow-human hybrid, with what seem to have been attached human elements, was birthed by a Holstein cow near Buckeye, Arizona, in 1913.

The following is a list of other reported hybrids with one or more exterogenetic parasitic attachments, often, seemingly randomly attached:

- A horse that had parasitic deer hooves attached to its legs above its ordinary hooves (pictured here);

- Half a dozen cases of chickens with human hands or feet as parasitic attachments (these reports are collected here);

- A fish with parasitic frog legs was pictured in the scholarly journal Miscellanea Curiosa (more information here);

- A duckling with the leg of a chicken attached to the top of its head (watch a video showing this animal here);

- An ostensible dog-goat hybrid with polymelia and a doglike leg attachment (as shown in the picture below).

- A probable horse-cow hybrid with the general appearance of a colt, but affected by polymelia and having a single cowlike hoof (as described in the Vermont news notice below).

- A cyclopean pig-human hybrid that was mostly like a piglet, but which had its single eye replaced by a human face (pictured and discussed below).

An ostensible dog-goat hybrid with polymelia and a doglike leg attachment, described on pages 197-198 of the June 14, 1683, issue of Journal des Sçavans, the first academic journal published in Europe. Note that the rear foot labeled C is the one the report says was shaped like a dog paw. (A translation of this report can be read here.)

An ostensible dog-goat hybrid with polymelia and a doglike leg attachment, described on pages 197-198 of the June 14, 1683, issue of Journal des Sçavans, the first academic journal published in Europe. Note that the rear foot labeled C is the one the report says was shaped like a dog paw. (A translation of this report can be read here.) A news notice describing a colt-like animal foaled in Williston, Vermont, a probable horse-cow hybrid affected by polymelia and having one foot like that of a cow (source: West Randolph, Vermont, Herald and News (Jun. 18, 1891, p. 1, col. 4). People confronted with abnormal births often choose to destroy the affected individual, as apparently occurred in the case described in the news notice. This practice has a long history, dating back to ancient times.

A news notice describing a colt-like animal foaled in Williston, Vermont, a probable horse-cow hybrid affected by polymelia and having one foot like that of a cow (source: West Randolph, Vermont, Herald and News (Jun. 18, 1891, p. 1, col. 4). People confronted with abnormal births often choose to destroy the affected individual, as apparently occurred in the case described in the news notice. This practice has a long history, dating back to ancient times.

Carl Gustav Carus

Carl Gustav Carus1789-1869

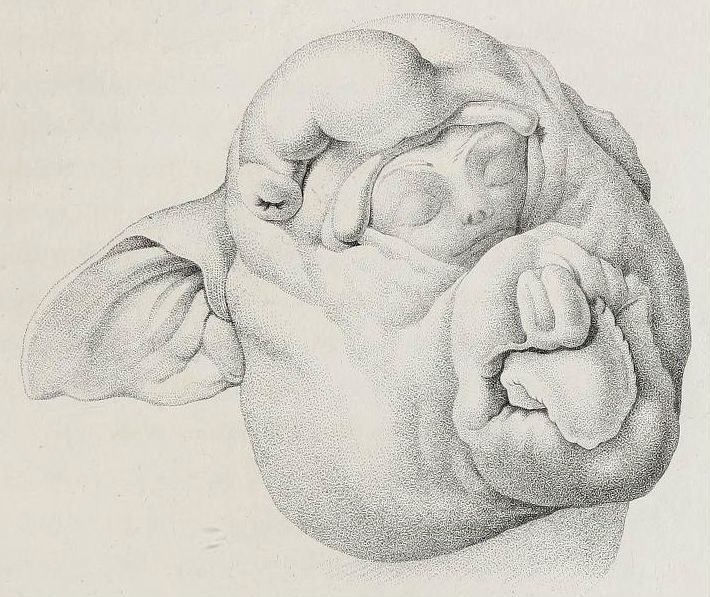

One of the most unusual and interesting cases of unequal hybrid conjoined twins was described by Carl Gustav Carus (1789-1869). Carus was a German physician who was also a naturalist, anatomist and painter. A friend of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Carus was credited by Sigmund Freud with originating one of the fundamental concepts of psychology, the unconscious.

During the course of his anatomical work, Carus published a detailed description of the head of an ostensible pig-human hybrid farrowed by a sow. (Carus 1841). This specimen had been sent to him from Hildburghausen§ by a certain Dr. Hartenstein. Carus not only wrote a lengthy description of his findings during the dissection of this head, but also employed his artistic talents to create a fine quality copper plate illustration of the specimen (shown below), and he explicitly states that its appearance is “very faithfully represented” (“sehr treu wiedergegeben”) by this illustration. Carus’s specimen is extremely unusual, not because it was a cyclops with a frontal proboscis, which are both features frequently seen in such human-pig hybrids, but rather because the site, of what in other specimens would have been a cyclopean eye, is filled by what appears to be a human face. This individual, then, represents a pig with a human parasitic twin. This bizarre tertium quid was born alive.*

The head of a cyclopean ostensible pig-human hybrid with a frontal proboscis, and a human face on, or in place of, its single eye, as depicted by Carl Gustav Carus. Carus states that the appearance of the specimen is “very faithfully represented” (“sehr treu wiedergegeben”) by this illustration (copperplate engraving, source: Acta Academiae Caesareae Leopoldino-Carolinae Germanicae Naturae Curiosorum, 1841, vol. XIX, p. 2, Plate LXXIV).

The head of a cyclopean ostensible pig-human hybrid with a frontal proboscis, and a human face on, or in place of, its single eye, as depicted by Carl Gustav Carus. Carus states that the appearance of the specimen is “very faithfully represented” (“sehr treu wiedergegeben”) by this illustration (copperplate engraving, source: Acta Academiae Caesareae Leopoldino-Carolinae Germanicae Naturae Curiosorum, 1841, vol. XIX, p. 2, Plate LXXIV).

Equal hybrid conjoined twins. Conjoined twins are called “equal” when neither is more fully developed than the other. Such twins are reported, extremely rarely, in hybrids. For example, in Australia, a “calf” was reportedly born having two heads, one of them “like a bull-dog’s.” A description of this strange dog-cow hybrid, which appeared in the Windsor and Richmond Gazette the local newspaper (Oct. 13, 1894), reads,

There are other old reports about equal hybrid conjoined twins involving other types of mammalian crosses, dog x human (one reported case is pictured above, and others here and here); a sheep x human (described here); and sheep x hare. An old news report (Indianapolis News, Jul. 21, 1899, p. 6, col. 3) tells of a farmer who captured a snake equal hybrid conjoined twin. Another, rather strange case is described in the news notice reproduced below.

News notice about a lamb-lizard conjoined twin that appeared in the Wanganui, New Zealand, Chronicle (Dec. 5, 1876, p. 2). Canowie Station was a pastoral lease in the state of South Australia. At its height it grazed 60,000 sheep. In 1876, Canowie was under the management of Thomas Goode (1835-1926).

News notice about a lamb-lizard conjoined twin that appeared in the Wanganui, New Zealand, Chronicle (Dec. 5, 1876, p. 2). Canowie Station was a pastoral lease in the state of South Australia. At its height it grazed 60,000 sheep. In 1876, Canowie was under the management of Thomas Goode (1835-1926).

A case that seems rather akin to the foregoing was described in the St. John, Kansas, County Capital (Nov. 13, 1890, p. 2, col. 7; ||yyto2agn):

There is a similar seventeenth-century report about a mouse-human conjoined twin, reported by a physician. And Aldrovandi described a case involving a snake-human conjoined twin birthed by a woman at Cracow in Poland in 1494. Another reported case involved a cow-kangaroo hybrid described in the Kumara, New Zealand, Times (Jan. 10, 1883, p. 2):

Another, rather unusual case, which supposedly occurred in Raleigh, North Carolina (but that may simply be hoax or hearsay since no names are given and it supposedly happened in a far-distant city), was reported in a Natchez, Mississippi, newspaper, Green's Impartial Observer (Jan. 24, 1801, p. 1, col. 4):

A PRODIGY

“A most curious spectacle was exhibited in this city a few days ago.—A female of the canine species was delivered of the most perfect lusus naturae that has ever been beheld in this part of the world, or, I believe, in any other, I will give you as accurate a description as I can.

“Its shape more resembles that of a child, than anything else I can compare it to; indeed it appears to be a composition of the human and brute parts of the creation. It has three heads, viz., one on each shoulder, and another between them.The one in the middle is the exact representation of the human face; those on the shoulders no way differing from those of a dog. It has six legs, two of which stand upright on its back, and four tails. I forgot to mention that the middle head instead of being covered with hair similar to that of the body, is furnished with black curly hair, similar to that on the head of a negro; and hands instead of paws, are placed on the ends of those legs or arms (whichever they may be called) which stand upright on the back.

“The owner of this curious animal expects to make a fortune by it. He sets out in a few days on his travels, and will, no doubt, pass through Petersburgh, when you will see with your own eyes; and I dare say, you will be as little able to account for such a strange appearance as I can be.”

Obviously, the incidence of conjoined twins is elevated among hybrids given that there are at most a thousand separate reports about hybrids on this website, and yet there are on the order of ten separate cases of conjoined twins among them, which indicates an incidence among hybrids of about one percent (0.01), as opposed to the observed rate in general population of about 0.0002, or less.

A 1907 newspaper advertisement offering for sale a cow-pig hybrid conjoined triplet, an animal with the head of a pig attached to the bodies of three calves (source).

A 1907 newspaper advertisement offering for sale a cow-pig hybrid conjoined triplet, an animal with the head of a pig attached to the bodies of three calves (source).

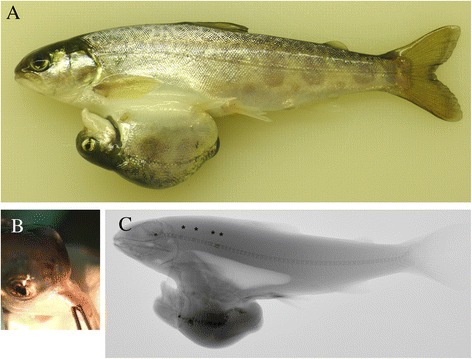

Hybrid conjoined twins occur, too, in fish (Fjelldal et al. 2016). a Atlantic salmon x Arctic char hybrid conjoined twins. b The parasitic twin's mouth was blocked. c Lateral radiograph. The host twin had 11 fused vertebrae (asterisks), while the parasitic exhibited various cranial and vertebral abnormalities (Image source: Fjelldal et al. 2016, Fig. 3).

Hybrid conjoined twins occur, too, in fish (Fjelldal et al. 2016). a Atlantic salmon x Arctic char hybrid conjoined twins. b The parasitic twin's mouth was blocked. c Lateral radiograph. The host twin had 11 fused vertebrae (asterisks), while the parasitic exhibited various cranial and vertebral abnormalities (Image source: Fjelldal et al. 2016, Fig. 3).

Some thoughts

Some of the reports just cited can be easily passed off as hoaxes or mistaken, or as figments accepted by the mere credulity of superstitious dupes. But given the fact that there are so many reports of such births and some of them authored by scholars, I tend to reject this interpretation, especially given that I agree with Michel de Montaigne’s observation (Essays I, 26) that

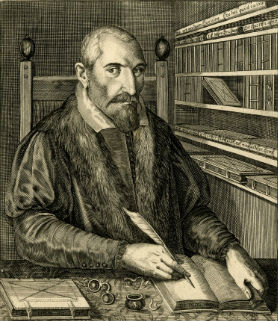

Fortunio Liceti

Fortunio Liceti

Not considering myself wiser than, say, Fortunio Liceti, Galileo's friend who reported the existence of a living cat with a exterogenetic human parasitic attachment, in his own hometown of Padua (and at a time when he himself lived there), I am left speculating how, from a biological standpoint, such an organism might have come into being. Obviously, such an event can be broken down into three consecutive stages: insemination, fertilization and development. The first of these steps could potentially occur in many ways. Only a bit of imagination is needed. Once the semen was in situ, it would find its way to the Fallopian tubes, and there a single feline spermatozoon would penetrate a single human egg. (Obviously, the producer of a spermatozoon need not be of the same kind as the owner of the egg that it penetrates. Otherwise there would be no hybrids in the world.) These two steps, then, are fairly straightforward.

But the course of subsequent development is another matter. In the case of identical non-conjoined twins, a single embryo at an early stage, prior to about the tenth day of development, divides into separate embryos that go on to become two separate, but genetically identical individuals. But in the case of conjoined twins, the division begins later, after the tenth day, stalls, and remains incomplete. The separated portions develop into duplicate bodily members (two heads, two bodies, etc.) and the undivided remainder becomes the non-duplicated moiety of the mature conjoined organism. Though it is somewhat surprising that development proceeds and that such partially duplicate organisms are viable, it is still fairly easy to imagine: the partially divided cell mass of the embryo grows by cell division and the separated parts of that mass map onto the duplicated parts of the mature organism, and the non-separated, onto the non-duplicated.

But what sort of mechanisms would have governed the development of hybrid conjoined twins? From my general research into mammalian and avian hybrids, I know that in many, more ordinary crosses the resulting hybrids look like composites of their two parents. For example, they might have the legs of one parent and the head and body of the other. Thus, zebra-ass hybrids often have the striped legs of a zebra even though the rest of the body looks like that of an ass. So it seems that by some unknown mechanism, the influence of the genetic material of one parent can predominate in one portion of the body, while that of the other predominates elsewhere. Indeed, in some crosses, the genes of one parent so dominate those of the other that the hybrids are phenotypically almost identical to the dominant parent.

Putting these facts together one can suppose that in a hybrid conjoined twin, the unknown mechanism just mentioned causes one of the two separated portions of the partially divided hybrid embryo to develop in a way similar to one parent, whereas the same mechanism or switch sets the remainder of the embryo to develop in a way similar to the other parent.

One can imagine various mechanisms that might bring such a result about, but such suppositions will remain mere hypotheses until the day that such distant hybrids become the subject of regular experimentation and observation.

Hercules and Cerberus, the three-headed dog who guarded the gates of Hades (Peter Paul Rubens, 1636, oil on panel). Perhaps Cerberus had a certain basis in fact?

Hercules and Cerberus, the three-headed dog who guarded the gates of Hades (Peter Paul Rubens, 1636, oil on panel). Perhaps Cerberus had a certain basis in fact?

Most shared on Macroevolution.net:

Human Origins: Are we hybrids?

On the Origins of New Forms of Life

Mammalian Hybrids

Cat-rabbit Hybrids: Fact or fiction?

Famous Biologists

Dog-cow Hybrids

Georges Cuvier: A Biography

Prothero: A Rebuttal

Branches of Biology

Dog-fox Hybrids

A dog-human equal conjoined twin (Source:

A dog-human equal conjoined twin (Source: