Cow-human hybrids

Myth

Mammalian Hybrids

This page is an uncorrected draft for a section of my book Telenothians, which is now available here >>.

|

Some born of a cow have the foreparts of a man; others, on the contrary, spring up begotten of a woman but with the head of a cow.

—Empedocles, Fragments

|

Daedalus helping Pasiphae enter the wooden cow (artist: Giulio Romano, 1503)

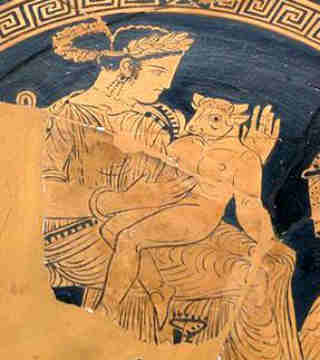

Daedalus helping Pasiphae enter the wooden cow (artist: Giulio Romano, 1503) Pasiphae with infant Minotaur (Tondo of an Attic red-figure kylix, 340-320 BCE)

Pasiphae with infant Minotaur (Tondo of an Attic red-figure kylix, 340-320 BCE)

Cow-human hybrids have been the subject of mythology and religious awe since the most ancient times. The best known example is that of the Minotaur of Greek legend. In that story Minos, the king of Crete and the husband of Pasiphae, prays for a white bull to sacrifice to Poseidon. But, as Apollodorus (Library and Epitome, 3.1.4) relates, Minos

Theseus slaying the Minotaur (Master of the Campana Cassoni, 16th century)

In ancient times, the story of Pasiphae was taken as a relation of real events, not only among the pagan Greeks and Romans, but even among the Jews. Thus, writing in the first century A.D., the Jewish scholar Philo Judaeus (The Special Laws, III, 8:46) asserted that it was to prevent the production of such mixed beings as the Minotaur that such behavior had been prohibited by Jewish law:

Montu (4th century BCE). Image:

Janmad

Montu (4th century BCE). Image:

Janmad

There are other, earlier deities, such as the Egyptian Montu (see image at right) and Apis, as well as the Mesopotamian Enkidu (see images below), which were often represented as a blend of human and cow. The Temple of Montu at Medamud was first built during the Old Kingdom era, that is, in the third millennium BCE. Worship of Apis and Enkidu dates back to at least an equally early date. Likewise, a guardian of the Underworld in Chinese mythology, known in English translation as Ox-head, had a bull head and a human body. And even today, the Devil is often represented in Christian publications as a kind of cow-human hybrid with horns, cloven hooves and a tail.

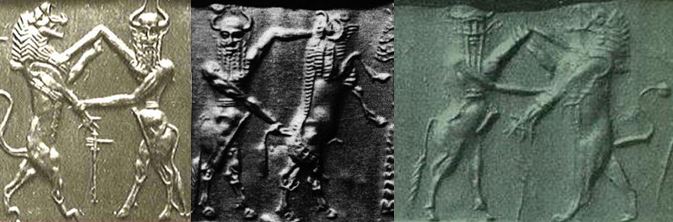

Cylinder seal impressions of the Mesopotamian cow-human hybrid god Enkidu (aka Eabani). Note similarity to Christian depictions of Satan.

Cylinder seal impressions of the Mesopotamian cow-human hybrid god Enkidu (aka Eabani). Note similarity to Christian depictions of Satan.

Lower bodies of Oannes and a bull-man (Pasargadae, Iran, 6th century BC).

Lower bodies of Oannes and a bull-man (Pasargadae, Iran, 6th century BC).

Many silver tetradrachms, such as those shown at right, were issued by the city of Gela during the fifth century BCE. Stamped with an image of a cow-human hybrid, they honored the river god Gelas for whom the city was named. Gela, which stood on the southern coast of Sicily, was a major city during the classical Greek period with a population of around 100,000. Famously, the tragedian Aeschylus died there in 456 BCE when a passing eagle dropped a turtle on his head. In Hellenic culture river gods were often represented as man-headed bulls, as they had been in earlier Etruscan culture (Molinari and Sisci 2016). An example appears in this passage from an ancient Greek tragedy in which a woman describes her courtship by a river god:

who took three forms to ask me of my father:

a rambling bull once, then a writhing snake

of gleaming colors, then again a man

with ox-like face: and from his beard’s dark shadows

stream upon stream of water tumbled down.

Such was my suitor.

(translated by Robert Torrance)

Rape of Europa (detail) by Rembrandt

Rape of Europa (detail) by Rembrandt

Another mythical cow-human hybrid, the Chichevache, a human-faced cow, appears also in The Canterbury Tales. According to Chaucer, it fed only on obedient and faithful wives and was therefore perpetually gaunt with hunger:

Lat noon humylitee youre tonge naille,

Ne lat no clerk have cause or diligence

To write of yow a storie of swich mervaille,

As of Grisildis pacient and kynd,

Lest Chichevache yow swelwe in hire entraille!

The Oxford English Dictionary says Chaucer’s is the earliest known use of the word chichevache in English. In French, chiche vache means “greedy cow” and was in use as an epithet in that language at least as early as the 13th century.

One story, told by Gerald of Wales (c. 1147 – c. 1223), is so old as to occupy the boundary region between history and myth. Gerald was an Anglo-Norman historian who, as royal clerk to King Henry II of England, traveled widely and wrote extensively on Henry’s realm. Edward Augustus Freeman described him as “one of the most learned men of a learned age.” In his account of Ireland (Topographia Hibernica, 1188, § II, xxi), Gerald tells of a cow-human hybrid that, he claims, dined on a regular basis with the Norman lords at Wicklow Castle (see also Expugnatio Hiberniae for the year 1176). Gerald gave his account of this creature the title Of a Man Half Bull and a Bull Half Man:

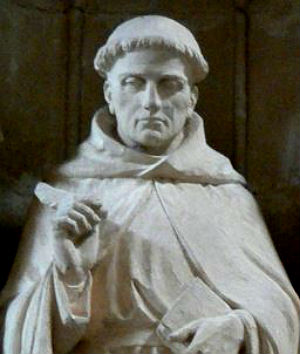

Gerald of Wales

Gerald of Wales

Near Wicklow, at the time when Maurice FitzGerald first gained lordship there was seen a human prodigy, if indeed it is correct to say “human.” For while the creature had a human body, his extremities were those of a cow. To the joints which normally connect the hands to the arms, and the feet to the calves, were instead attached the hooves of an ox. His head was bald, except for a few patches of down in place of ordinary hair. The eyes were large, cow-like in their roundness and color. The face below was flat—merely two nostrils, with no protruding nose. He spoke no words and his voice was like that of a cow.

Long an attendant of Maurice’s court, he came every day to meals, and what he was given to eat, he gripped in the cleft of his hooves which served him as hands, and so conveyed it to his mouth. However, because the [English] nobles of the castle often mocked the Irish for getting such things on cattle, they at last, in their malice and spite, waylaid and killed him, which he little deserved. For shortly before the English arrived on that island [i.e., Ireland] a cow had birthed this man-calf in the mountains of Glendalough … Thus, you might well suppose that “a man half-bull and a bull half-man” had been created once again [here, Gerald refers to Pasiphae and the Minotaur]. For almost a year he remained with the cattle, following and nursing his mother. But at last, since he was more human than cow, he was brought over into human society. [Translated by E. M. McCarthy. Original Latin]

Cow-human hybrids: Nonfiction reports >>

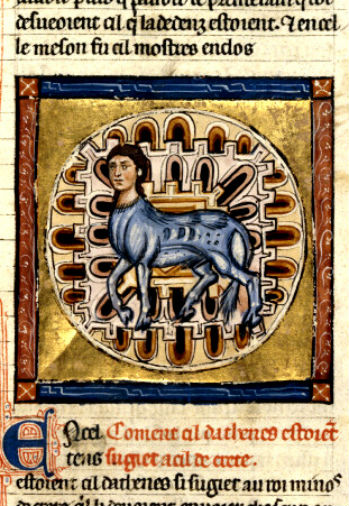

Cow-human hybrid from Histoire ancienne jusqu'à César, Jerusalem, 1260-1270 CE, Dijon - British Museum ms. 0562.

Cow-human hybrid from Histoire ancienne jusqu'à César, Jerusalem, 1260-1270 CE, Dijon - British Museum ms. 0562.  Sumerian copper protome in the form of a bull-man, Early Dynastic III, circa 2550-2250 B.C., 4 inches wide.

Sumerian copper protome in the form of a bull-man, Early Dynastic III, circa 2550-2250 B.C., 4 inches wide.

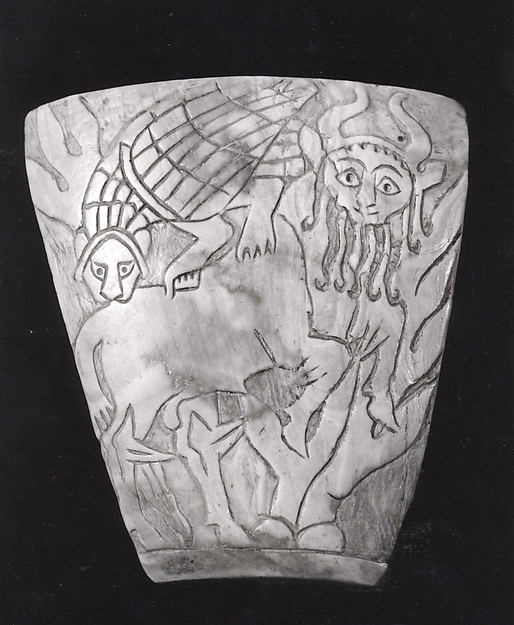

Plaque carved from a piece of shell incised with the image of a human-headed bull attacked by a lion-headed eagle. Sumerian, Early Dynastic IIIa, ca. 2600–2500 B.C. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Plaque carved from a piece of shell incised with the image of a human-headed bull attacked by a lion-headed eagle. Sumerian, Early Dynastic IIIa, ca. 2600–2500 B.C. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Two bull-men flanking a tree trunk surmounted by a sun disc (Molded ceramic plaque, Old Babylonian Period, ca. 2000–1600 B.C., southern Mesopotamia, source: Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Two bull-men flanking a tree trunk surmounted by a sun disc (Molded ceramic plaque, Old Babylonian Period, ca. 2000–1600 B.C., southern Mesopotamia, source: Metropolitan Museum of Art).

The goddess Durga attacking the buffalo demon Mahishasura (Mahishasuramardhini Cave, Mahabalipuram, India).

The goddess Durga attacking the buffalo demon Mahishasura (Mahishasuramardhini Cave, Mahabalipuram, India).

By the same author: Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World, Oxford University Press (2006).

Most shared on Macroevolution.net:

Human Origins: Are we hybrids?

On the Origins of New Forms of Life

Mammalian Hybrids

Cat-rabbit Hybrids: Fact or fiction?

Famous Biologists

Dog-cow Hybrids

Georges Cuvier: A Biography

Prothero: A Rebuttal

Branches of Biology

Dog-fox Hybrids

Enlarge

Enlarge