The Death of Pliny the Elder

Famous Biologists

Probable appearance of Vesuvius at the time of the death of Pliny

Probable appearance of Vesuvius at the time of the death of Pliny|

|

EUGENE M. MCCARTHY, PHD

An account of the death of Pliny the Elder is given in a letter from his nephew, Pliny the Younger, to the historian Tacitus. The following is the relevant passage (from Letter 6.16, translated by E. M. McCarthy):

The Death of Pliny

… He [Pliny the Elder] was at that time with the fleet under his command at Misenum. On August 24th [79 AD], about one in the afternoon, my mother asked him to look at a cloud of the most peculiar size and shape. He had been sunbathing earlier, which he had followed with a cold bath and a light lunch. He had then returned to his books. But he rose at once and went to high ground where he could get a better view of this remarkable phenomenon.

A cloud — it was unclear, at that distance, which mountain emitted it, although it was later found to be Mount Vesuvius — was ascending to the heavens. I can give no better description of it than by likening it to a pine tree. For it shot up to a tremendous height like a tree trunk and then spread out at its summit into branches, which arose, I suppose, either by the decreasing speed as it shot upwards, or by the weight of the cloud pressing back upon itself. At times it was bright, at others, dark and mottled, depending on the density of the earth and cinders within it.

To a man of such learning as my uncle, this phenomenon seemed extraordinary and well worth investigation. He ordered a light ship prepared, and told me I could come along if I liked. But I said I would rather go on with my work. And, as a matter of fact, he had given me something to write.

As he was coming out of the house, he received a note from Rectina, the wife of Bassus, who was terrified at the danger. For her villa lay at the foot of Vesuvius, and there was no way to escape except by sea. She therefore begged my uncle to come over and save her.

So he changed his mind, and what began as a scientific expedition, now became a noble and selfless mission of rescue. He ordered galleys to put to sea, and went on board, planning not only to save Rectina, but also to bring aid to the numerous towns of that beautiful coast. Hurrying, then, to the very place that others fled, he set his course directly for the center of danger. And he did this with such calm and presence of mind that he actually dictated his observations on the dreadful spectacle to an amanuensis en route.

|

| Map of Gulf of Naples showing the names and locations of towns at the time of the death of Pliny. The darkened area is the region where heavy downfalls of ash and pumice occurred. If Pliny had merely remained at Misenum instead of approaching Vesuvius to investigate, he would surely have survived. Image: Mapmaster |

He was now so close to the mountain that the cinders, which grew thicker and hotter as he approached, fell into the ships, together with pumice stones, and black burning rock. The fleet was threatened, too, not only with running aground — for the sea had suddenly retreated — but also by huge blocks of lava rolling down from the mountain, and obstructing all the shore.

At this point, he hesitated, thinking whether to turn back, but in the end he urged the pilot on. “Fortune," he said, “favors the brave. Let us seek Pomponianus!” Pomponianus [his friend] was then at Stabiae, where the sea forms a slight bay in the shore. He had already ordered all of the baggage back on board. For though there was not as yet any actual danger, they were within sight of it, and in fact, very near. If the situation seemed to worsen in any way, his plan had been to set back out to sea as soon as the wind turned, which at the time was blowing straight in toward shore.

But the wind was such that they could sail to Pomponianus, so they did. Finding him extremely apprehensive, my uncle embraced him, and urged him to take heart, which he did more easily by the fact that he, my uncle, seemed unconcerned himself. He ordered a bath, and then, after bathing, sat cheerfully down to dinner, or at least, which is just as heroic, with every appearance of cheerfulness. This while great blasts of flame from Vesuvius glared forth in the night. My uncle, in order to reassure his friend, said the fires were only some of the villages burning that the country folk had abandoned to the flames.

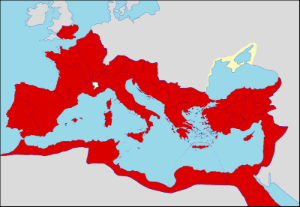

Roman Empire at the time of the death of Pliny.

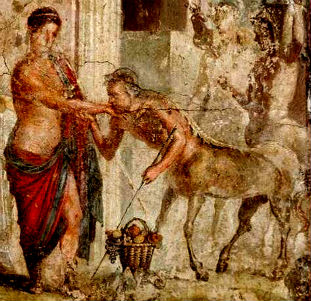

Roman Empire at the time of the death of Pliny. The centaur Chiron paying homage to Pirithous (Pompeii) Enlarge image

The centaur Chiron paying homage to Pirithous (Pompeii) Enlarge image

Afterward he went to bed, and it's clear he slept deeply. For the attendants outside could hear his breathing, which was usually quite heavy due to his being overweight. But they had to wake him since the court outside his room was filling with stone and ash, so that if he stayed longer, he would have been blocked up inside. So he got up, and went to Pomponianus and the others, who had been too upset even to consider the idea of sleeping.

They tried to decide whether it would be wiser to remain inside their houses—which now were being shaken to their foundations with repeated, violent concussions from the eruption—or to flee to the open fields, where the stones and cinders rained down in such heavy showers that, although they were individually light, they seemed to threaten annihilation. In the end, they chose to go outdoors.

So they went out with pillows tied on top of their heads with napkins, their only defense against the storm of falling stones. Elsewhere it was day, but there the darkness was deeper than thickest night, and they had to use lights to find their way. They decided to go down to the shore to see whether they could escape by sea, but the waves were still running too high.

There my uncle lay down on a sail that had been spread for him, and called twice for some cold water, which he drank. Then a rush of flame, with the reek of sulfur, made everyone scatter, and made him get up. He stood with the help of his servants, but at once fell down dead, suffocated, as I suppose, by some potent, noxious vapor. He had always had a weak respiratory tract, which was often inflamed and obstructed.

When light returned, which was not until the third day, his body was found intact, in the same clothes he had died in.

Death of Pliny - © Macroevolution.net

Most shared on Macroevolution.net:

Human Origins: Are we hybrids?

On the Origins of New Forms of Life

Mammalian Hybrids

Cat-rabbit Hybrids: Fact or fiction?

Famous Biologists

Dog-cow Hybrids

Georges Cuvier: A Biography

Prothero: A Rebuttal

Branches of Biology

Dog-fox Hybrids