Deer-human Hybrids

Mammalian Hybrids

Detail from Diana and Actaeon by Giuseppe Cesari (1568-1640).

Detail from Diana and Actaeon by Giuseppe Cesari (1568-1640).

|

Rough was his skin with sudden hair o’ergrown.

—Ovid, Metamorphoses

|

The goddess Diana and a stag (Lucas Cranach the Elder, detail from Apollo and Diana).

The goddess Diana and a stag (Lucas Cranach the Elder, detail from Apollo and Diana).

The following quoted report should not be taken at face value. Any claim that deer-human hybrids are possible could only be corroborated via the evaluation of an actual specimen.

In his Observationes atque cogitationes non nullae de monstris (1748, pp. 6-8, sec. 6), Johann Jakob Huber (1707-1778), a professor of anatomy and surgery at Göttingen University, describes a boy most of whose torso was covered in a pelt like that of a deer. The following is a translation of the relevant passage in the Latin original. Huber states that the boy in question

Generally speaking, cervus, the Latin word used by Huber, refers to the Red Deer, Cervus elaphus (pictured at left), which is in accord with his description of the pelt as red.

Red deer is, generally speaking, a European name for these animals. In North America, where they are sometimes treated as a separate species (Cervus canadensis), they are called elk or wapiti.

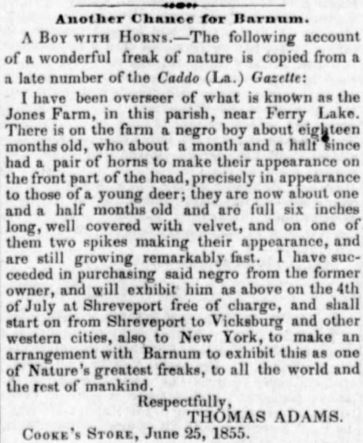

And slightly more recent report about a deer-human hybrid appeared in the Washington, D.C., newspaper Triweekly Washington Sentinel (Aug. 7, 1855, p. 3):

There seem not to be any other allegations of ostensible deer-human hybrids on record. However, there are innummerable reports about a very similar hybrid: cow x human.

Supplementary material:

A myth about a deer-human hybrid

The Nabaloi people of the Philippines tell a story (transcribed here from Moss 1920, p. 349) about a monster named the Kolas, a deer-human hybrid.

The Monster Kolas

Finally the deer gave birth to a male. The offspring had horns and was four-footed like a deer, but also had arms like a man. Its feet and face were like the feet and face of a man, but its hair was like the hair of a deer. Its name was Kolas.

When Kolas was one year old, the hunter killed his mother and ate her for food. Kolas was angry with his father. That night Kolas took the skin of his mother, and wrapped it around his body. He took the spear and shield of the hunter and ran away to the forest. He became the master of all the deer.

Many times the hunters tried to kill him; but he had his shield, spear and the skin of his mother. Also he could run faster than the dogs. When the dogs pursued Kolas, he killed them with his horns and his spear. Sometimes he would hide in the forest, and kill the people who were passing. At night he would go to the settlement, and kill the people who were sleeping.

Finally the people made deep pits and covered them with grass and earth. One night when Kolas was going to the settlement, he fell into a pit. Then early the next day, the people found him. They covered the pit with earth and stones, and buried Kolas.

A fictional account of a roe deer adopting a human child (from The History of Hayy Ibn Yaqzan by Abu Bakr Ibn Tufail, translated from the Arabic by Simon Ockley, 1929, pp. 44-45 & 51-53)

The Nails and Timbers of the Ark had been loosen’d when the Waves cast it into that Thicket; the Child being very hungry wept and cry’d for help and struggled. It happened that a Roe which had lost her Fawn, heard the Child cry, and following the Voice (imagining it to have been her Fawn) came up to the Ark, and what with her digging with her Hoofs from without, and the Child’s thrusting from within, at last between ’em both they burst open a Board of the Lid. Thereupon she was mov’d with Pity and Affection for him, and freely gave him suck; and she visited and tended him continually, protecting him from all Harm.

...

They say that this Roe liv’d in good and abundant Pasture so that she was fat, and had such plenty of Milk, that she was very well able to maintain the little Child; she stay’d by him and never left him, but when hunger forc’d her; and he grew so well acquainted with her, that if at any time she staid away from him a little longer than ordinary, he’d cry pitifully, and she, as soon as she heard him, came running instantly; besides all this, he enjoy’d this hap piness, that there was no Beast of prey in the whole Island.

Thus he went on, living only upon what he Suck’d till he was Two Years Old, and then he began to step a little and Breed his Teeth. He always followed the Roe, and she shew’d all the tenderness to him imaginable; and us’d to carry him to places where Fruit Trees grew, and fed him with the Ripest and Sweetest Fruits which fell from the Trees; and if they had hard Shells, she us’d to break them for him with her Teeth; still Suckling him, as often as he pleas’d, and when he was thirsty she shew’d him the way to the water. If the Sun shin’d too hot, she shaded him; if he was cold she cherish’d him and kept him warm; and when Night came she brought him home to his old Place, and covered him partly with her own Body, and partly with some Feathers taken from the Ark, which had been put in with him when he was first expos’d. Now, when they went out in the Morning, and when they came home again at Night, there always went with them an Herd of Deer, which lay in the same place where they did; so that the Boy being always amongst them learn’d their voice by degrees, and imitated it so exactly that there was scarce any sensible difference; nay, when he heard the voice of any Bird or Beast, he’d come very near it. But of all the voices which he imitated, he made most use of the Deers, and could express himself as they do, either when they want help, call their Mates, when they would have them come nearer, or go farther off. (For you must know that the Brute Beasts have different Sounds to express these different things.) Thus he contracted such an Acquaintance with the Wild Beasts, that they were not afraid of him, nor he of them.

Diana and Actaeo

It was midday, and the sun stood equally distant from either goal, when young Actaeon, son of King Cadmus, thus addressed the youths who with him were hunting the stag in the mountains:—

“Friends, our nets and our weapons are wet with the blood of our victims; we have had sport enough for one day, and tomorrow we can renew our labours. Now, while Phoebus parches the earth, let us put by our implements and indulge ourselves with rest.”

There was a valley thick enclosed with cypresses and pines, sacred to the huntress queen, Diana. In the extremity of the valley was a cave, not adorned with art, but nature had counterfeited art in its construction, for she had turned the arch of its roof with stones, as delicately fitted as if by the hand of man. A fountain burst out from one side, whose open basin was bounded by a grassy rim. Here the goddess of the woods used to come when weary with hunting and lave her virgin limbs in the sparkling water.

One day, having repaired thither with her nymphs, she handed her javelin, her quiver, and her bow to one, her robe to another, while a third unbound the sandals from her feet. Then Crocale, the most skilful of them, arranged her hair, and Nephele, Hyale and the rest drew water in capacious urns. While the goddess was thus employed in the labors of the toilet, behold Actaeon, having quitted his companions, and rambling without any especial object, came to the place, led thither by his destiny. As he presented himself at the entrance of the cave, the nymphs, seeing a man, screamed and rushed towards the goddess to hide her with their bodies. But she was taller than the rest and overtopped them all by a head. Such a color as tinges the clouds at sunset or at dawn came over the countenance of Diana thus taken by surprise. Surrounded as she was by her nymphs, she yet turned half away, and sought with a sudden impulse for her arrows. As they were not at hand, she dashed the water into the face of the intruder, adding these words: “Now go and tell, if you can, that you have seen Diana unapparelled.” Immediately a pair of branching stag’s horns grew out of his head, his neck gained in length, his ears grew sharp-pointed, his hands became feet, his arms long legs, his body was covered with a hairy spotted hide. Fear took the place of his former boldness, and the hero fled. He could not but admire his own speed; but when he saw his horns in the water, "Ah, wretched me!" he would have said, but no sound followed the effort. He groaned, and tears flowed down the face which had taken the place of his own. Yet his consciousness remained. What shall he do?—go home to seek the palace, or lie hid in the woods? The latter he was afraid, the former he was ashamed to do. While he hesitated the dogs saw him. First Melampus, a Spartan dog, gave the signal with his bark, then Pamphagus, Dorceus, Lelaps, Theron, Nape, Tigris, and all the rest, rushed after him swifter than the wind. Over rocks cliffs, through mountain gorges that seemed impracticable, he fled and they followed. Where he had often chased the stag and cheered on his pack, his pack now chased him, cheered on by his huntsmen. He longed to cry out, “I am Actaeon; recognize your master!” but the words came not at his will. The air resounded with the bark of the dogs. Presently one fastened on his back, another seized his shoulder. While they held their master, the rest of the pack came up and buried their teeth in his flesh. He groaned,—not in a human voice, yet certainly not in a stag’s,—and falling on his knees, raised his eyes, and would have raised his arms in supplication, if he had had them. His friends and fellow-huntsmen cheered on the dogs, and looked everywhere for Actaeon, calling on him to join the sport. At the sound of his name he turned his head, and heard them regret that he should be away. He earnestly wished he was. He would have been well pleased to see the exploits of his dogs, but to feel them was too much. They were all around him, rending and tearing; and it was not till they had torn his life out that the anger of Diana was satisfied.

(Source: Bullfinch’s Mythology)

A deer-human hybrid. Detail from The Witches’ Sabbath by Frans Francken the Younger (1581-1642).

A deer-human hybrid. Detail from The Witches’ Sabbath by Frans Francken the Younger (1581-1642).

Woman astride a deer. Artist: Franz von Bayros (1866-1924).

Woman astride a deer. Artist: Franz von Bayros (1866-1924).