On the Origins of New Forms of Life

1.8: Definitions of Species

(Continued from the previous page)

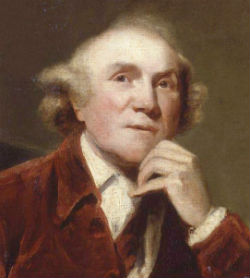

Ernst Mayr

Ernst Mayr

Definitions of Species. Many definitions of species have been proposed since the time of Locke and Ray. There are, however, two main types of definitions that biologists generally use: morphological and biological. The former places weight on resemblance, the latter, on genetic isolation.

The morphology of an organism is its characteristic form, coloration, and structure. Morphological definitions, embraced primarily by researchers engaged in sorting and naming specimens, emphasize resemblance and distinctness. Under this approach to biological classification, similar specimens are assigned to the same category, dissimilar ones, to different categories. Definitions of species on the basis of morphology have been criticized because

- there are many cases where morphologically similar or identical organisms are unable to interbreed;

- large morphological differences sometimes exist between organisms that can and do interbreed;

- degrees of morphological difference form a continuum and there is no objective criterion for saying how much difference between two types is required if they are to be treated as separate species.¹

Nonetheless, the vast majority of populations and specimens treated as species have been so described on the basis of morphology alone. For example, Linnaeus' plant taxonomy was based solely on the number and arrangement of the reproductive organs. This taxonomy was the starting point of all future biological classifications of plants. Darwin used various definitions of species, but he did at times use morphological criteria. Thus, in the Origin (1859: 56) he tells the reader that

But only a few pages earlier (p. 47) he says that

Such matters are still often determined by vote instead of by any objective criterion. (The writer has frequently seen this method used in connection with avian taxonomy.) But there is no reason why a committee lacking an objective criterion should be more correct than individuals lacking an objective criterion.

Naturalists specializing in a particular group of organisms (for example, mammals) usually have a sense of the amount of difference that typically distinguishes types treated as separate species. But this is more a matter of intuition than definition. Their opinion merely reflects their personal experience regarding how much difference is typically required for two types of organisms to be treated as separate species. It tells us nothing about whether such treatment is actually correct. Nor does it provide a rule for the construction of satisfactory definitions of species.

Actually, Darwin probably had it right when he said that "in order to decide whether to rank a plant as a species or a variety, we must rely on the opinions of the best & most cautious Botanists, who, however may of course be easily mistaken. [!]"²

Biological definitions of species. Though morphological definitions of species have been used in biological classification for centuries, and though morphology has served as the basis for distinguishing the great majority of the various types now treated as species, throughout the latter half of twentieth century most evolutionary biologists espoused what are termed "biological" definitions of species. Thus, Ernst Mayr (1963: 19) noted that

Among the many definitions of species offered, Mayr's has enjoyed the greatest popularity. But there are both practical and conceptual difficulties with its application. As Mayr (1982: 273) himself comments, "The history of the numerous attempts to achieve a satisfactory biological species definition has been told repeatedly."³

Moreover, even when Mayr first proposed his definition nearly seventy years ago, biological definitions of species were anything but new. Mayr's teacher Erwin Stresemann (1919: 64) asserted that

In a letter to his friend Joseph Hooker dated October 22nd, 1864, Darwin himself used a biological definition: "I will fight you to the death," he writes Hooker,

Darwin (1872: xvi) notes, too, that "Von Buch, in his excellent Description physique des Isles canaries (1836, p. 147), clearly expresses his belief that varieties slowly become changed into permanent species, which are no longer capable of intercrossing."⁶ At about the same time, Matthew (1831) stated his belief that

John Hunter

John Hunter Buffon

Buffon

Even earlier, Hunter (1787: 253) writes that

In the mid-eighteenth century, Buffon explained the criteria he thought should be used in biological classification in deciding what forms to treat as species:

Thus, the definitions of species used by Buffon and Mayr are really quite similar, and subject to the same sorts of difficulties. The main difference is that Mayr introduces a bit of modern jargon ("reproductive isolation" to replace Buffon's "cannot mingle").

Mayr (1982: 257) himself notes that, from the seventeenth century through the end of the nineteenth, many naturalists interested in biological classification offered definitions of species that used "biological criteria to reconcile the seeming contradiction between conspicuous variation and the presence of a single essence." That is, these definitions sought to define species in such a way that all individuals taxonomically treated as belonging to the same species (treated as "conspecific") could be viewed as essentially the same, though they might differ morphologically from each other in many ways.

The function of Mayr's own concept is similar. He said, no matter what morphological and behavioral differences distinguish two individuals, they do not differ in any essential way and should be treated as a single species if they interbreed. NEXT PAGE >>

2. Stauffer (1987: 402).

3. Mayr (1982: 273).

4. Quoted in translation by Mayr (1942: 119).

5. Darwin and Seward (1903: 252).

6. Darwin (1872: xvi).

7. Quoted from ucmp.berkeley.edu/history/matthew.html.

8. Buffon (1749–1804: vol. IV, 384–386). Translated by E. M. McCarthy. Original French: "… l’âne ressemble au cheval plus que le barbet au levrier, et cependant le barbet et le levrier ne font qu’une même espèce, puisqu’ils produisent ensemble des individus qui peuvent eux-mêmes en produire d’autres, au lieu que le cheval et l’âne sont certainement de différentes espèces, puisqu’ils ne produisent ensemble que des individus viciés et inféconds. … on peut toûjours tirer une ligne de séparation entre deux espèces, c’est-à-dire, entre deux successions d’individus qui se reproduisent et ne peuvent se mêler, comme l’on peut aussi réunir en une seule espèce deux successions d’individus qui se reproduisent en se mêlant."

Most shared on Macroevolution.net:

Human Origins: Are we hybrids?

On the Origins of New Forms of Life

Mammalian Hybrids

Cat-rabbit Hybrids: Fact or fiction?

Famous Biologists

Dog-cow Hybrids

Georges Cuvier: A Biography

Prothero: A Rebuttal

Branches of Biology

Dog-fox Hybrids