Okapi: A giraffe-zebra hybrid?

Mammalian Hybrids

|

The rule is perfect: In all matters of opinion, our adversaries are insane.

|

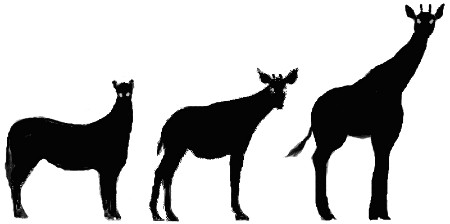

On their rumps and legs, okapis have striping like that of a zebra.

On their rumps and legs, okapis have striping like that of a zebra. The okapi has a giraffe-like head.

The okapi has a giraffe-like head.

(This article is an opinion piece explaining why the okapi, Okapia johnstoni, is of probable hybrid origin. It's part of the support material for the alternative theory of evolution offered on this website.)

Okapis mix traits otherwise seen only separately either in the giraffe or in the zebra, and under ordinary circumstances this fact would constitute strong evidence that okapis are giraffe-zebra hybrids. And yet, it seems no scientist has investigated this possibility. Why?

Well, apparently, scientists rely more on theory in this case than on observation. In trees representing accepted notions of evolutionary descent, giraffes and zebras are placed on widely separate branches, so it is generally believed that the two are simply too far apart to produce hybrids. Thus, it is not surprising that there are no reports from researchers who tried to create such hybrids. Experimentation does not occur because theory says it’s useless to try.

Scientists long ago assigned the okapi and the giraffe to the same taxonomic order (Artiodactyla) because they both have cloven hooves, and to the same family (Giraffidae) because they share certain distinctive features: Both have large eyes and ears, thin lips and an extraordinarily long, extensible tongue that allows them to lick their entire faces, even the ears; their backs slope upward from rump to withers; they also share the same dental formula: (i 0/3, c 0/1, pm 3/3, m 3/3) × 2 = 32. Both okapis and giraffes, unlike any other mammal, have molars with rugose enamel and bony horns that remain covered with skin throughout life (Nowak 1999, vol. 2, p. 1085). The two are therefore firmly linked.

Yet the rump and legs of an okapi are covered with black-and-white stripes exactly like those of a zebra. Perhaps, then, if okapis had solid hooves instead of cloven ones, they would be classified as perissodactyls (Order Perissodactyla) and would be considered more closely related to zebras than to giraffes? An okapi is about the same size as a Burchell’s zebra.

Other

Artiodactyl-equid Crosses:

The chromosome count of an okapi is also like that of a zebra, to which it is not supposed to be related, and unlike that of a giraffe. Giraffes have 30 chromosomes (Taylor et al. 1967; Hösli and Lang 1970; Koulischer et al. 1971), whereas okapis have a variable chromosome number of 44-46, depending on the animal in question; most seem to have 2n = 45 (Ulbrich and Schmitt 1969; Hösli and Lang 1970; Koulischer 1978). The chromosome number of Grevy’s zebra is 2n = 46 and plains zebras have 2n = 44 (Benirschke and Malouf 1967). Variation in chromosome count is itself unusual among mammals, but common in hybrids.

Okapis also produce high levels of abnormal sperm, which is consistent with the idea that they are the products of a distant hybrid cross. Thus, Penfold (2007) reports that 52% percent of the spermatozoa produced by these animals are morphologically abnormal (abnormal sperm is characteristic of hybrids). As those authors state, “okapi semen collected by electroejaculation routinely contain high numbers of non-motile and plasma membrane-damaged spermatozoa, apparently unrelated to season or the length of time since the male was housed with a breeding female.” Various studies report that okapis have poor reproductive success (Benirschke 1978; Leus 2004; Loskutoff 1997; Rabb 1978; Raphael 1988; Raphael et al. 1986; Van Puijenbroeck and Leus 1996), just as is the case with many kinds of hybrids.

Image: Derek Keats

It is, of course, well known that giraffes and zebras exist in mixed herds in various parts of Africa, and therefore are in potential breeding contact (these regions include those where okapis occur).

However, zebras are much smaller than giraffes, which might lead one to suppose that they would be physically unable to mate. But hybrids sometimes occur between animals where the disparity in size is much greater. Male Steller sea-lions (Eumetopias jubatus) often mate, and sometimes even successfully hybridize, with female California sea-lions (Zalophus californianus). And yet, the former average around 1100 lbs., while the latter weigh only around 200 lbs., a ratio of 5.5:1 (the female often dies in such encounters). Such large disparities are nothing unusual in hybrid crosses. Florio (1983) reports a case of a lion father who weighed 550 pounds (250 kg), while the leopard mother weighed a mere 84 pounds (38 kg), a ratio of 6.54:1.

In the case of a full-grown male giraffe, which typically weighs some 2,600 pounds (1,180 kg), with a female zebra, which would weigh about 770 pounds (350 kg), the weight ratio is only 3.4:1, that is, the difference is less disparate than in either of the two crosses just mentioned.

And this difference would be even smaller with the cross reversed, that is, with a female giraffe and a male zebra. Giraffe females weigh nearly a thousand pounds less than males, while zebra males weigh a bit more than females, which would yield a ratio closer to 2:1, not at all unusual in a hybrid cross. Moreover, giraffes do sometimes lie down, and a male zebra would, of course, have much better access to a recumbent female giraffe.

A final fact consistent with the idea that okapis might be giraffe-zebra hybrids is their rarity, which is typical of sporadically produced, reproductively deficient, hybrids. The IUCN rates the okapi as endangered, although it also states that “there is no reliable estimate of current population size.”

Comments on the Internet are frequent to the effect that okapis look like a giraffe-zebra cross. And many people even say okapis are obvious giraffe-zebra hybrids. This speculation is due to okapis combining, as has already been mentioned, the traits of giraffes and zebras. And this belief has been widespread ever since the okapi became known to science. Writing in the first years of the twentieth century, only four years after the discovery of the okapi, the British naturalist Richard Lydekker (1904, p. 474) commented that “the absurd idea that the okapi

1849–1915

1847-1929

So Lydekker is implying that if the okapi were a hybrid, multiple specimens would not be known. But he was writing at time when very little was known about natural hybrids and it was widely imagined that natural hybrids never occurred. Today a wide variety of natural hybrids, from many thousands of different crosses, are known.

Sir E. Ray Lankester (1905, pp. 163-165), Director of the Natural History Departments of the British Museum, concurred with Lydekker’s opinion that the okapi could not be a giraffe-zebra hybrid: “As they live in these immense dark gloomy and damp forests they are very difficult to shoot or to catch, and moreover

Today, Lankester’s assertion that “It is a fact that mules or hybrids never are produced by animals living in their natural conditions” seems laughably inaccurate. It is now well known that thousands of crosses occur naturally among birds, mammals and a wide variety of other animals.

Bray of a zebra:

And as to his allegation that “no one has ever produced, even in captivity, a hybrid between any creatures so unlike each other as a double-hoofed and a single-hoofed mammal,” there is nothing in the structure itself of hooves that prevents interbreeding. After all, there are breeds of pig (“mulefoot pigs”) that have a solid hoof, like that of a horse or zebra , and yet they can mate freely with ordinary cloven-hoofed pigs. Such pigs have been known since ancient times (see Pliny, Natural History, XI, CVI). And this trait can arise as a single-gene mutation, which suggests it’s not the profound distinction that it has so often been claimed to be (more about mulefoot pigs).

However, in the minds of many people who raise objections on this difference of single and double hoof, the key issue seems to be that this is the separating factor between Order Perissodactyla (odd-toed ungulates) and Order Artiodactyla (even-toed ungulates), two major divisions of Class Mammalia. Zebras belong to the former of these two orders and giraffes to the latter. True, this is an old distinction in taxonomy, but it is unclear why two animals’ differing in this way should necessarily ban them from producing hybrids. If the okapi were such a hybrid, then obviously hybrids between different orders would in fact be possible. Indeed, it would seem from evidence collected elsewhere on this website, that horse-cow hybrids are in fact possible, which is also a perissodactyl-artiodactyl cross.

But only experimentation can determine the true status of the okapi. For example, it would be interesting to see the results of repeated artificial insemination of female giraffes with zebra sperm, and vice versa. Genomic analysis would also be of interest.

Distant hybrids. And it is not as if there were no evidence of distant crosses among animals occurring. Actually, there’s a great deal. It’s just that not everyone accepts that evidence. A cross between a giraffe and a zebra would be interordinal. Among birds, there are numerous reports of such crosses. Here are some examples:

- Pigeon (Columba livia) × Domestic Fowl (Gallus gallus);

- Domestic Duck (Anas platyrhynchos) × Domestic Fowl;

- Lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae) × Domestic Fowl;

- Budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus) × Domestic Canary (Serinus domesticus);

- Turquoisine Parakeet (Neophema pulchella) × Domestic Canary.

to name a few. For mammals, among many, we have:

- Cat × Rabbit;

- Pig × Human;

- Horse × Cattle, a rather similar case to zebra × giraffe;

- Human × Cattle;

- Domestic Dog × Cattle.

Using artificial insemination, Newman (1915, 1917 and 1918) obtained interordinal hybrids from various fish crosses. In particular, he describes hybrids he produced between mackerel and mud minnow (the latter belongs to Order Cyprinodontiformes, and the former to Order Perciformes). In another early study Meehan (1900) reported that under carefully controlled conditions he and his colleagues had created hybrids between the fish orders Salmoniformes and Perciformes. They inseminated Brown Trout (Salmo trutta) eggs with Yellow Perch (Perca flaven) milt, and obtained viable hybrids, though only a very small percentage of the eggs hatched (0.125%). Zhang et al. (2014, p. 890) say that two other types of interordinal hybrids involving perch have been observed, from the cross Megalobrama amblycephala (♀) of Cypriniformes and Siniperca chuatsi (♂) of Perciformes, and from Hypophthalmichthys molitrix (♀) of Cypriniformes bred with Pagrosomus major (♂), also of Perciformes. And there are innumerable reports about fish crosses that are even more distant, such as this one about a viable adult hybrid between a buffalofish (Ictiobus sp.) and a catfish (probably Ictalurus furcatus). The former is generally assigned to Euteleostei, and the latter to Otocephala, groups that are commonly said to have diverged some 240 million years ago. Interordinal crosses among fish can be considered at least as distant as interordinal crosses among mammals, given that fish are generally considered more diverse than mammals and of far more ancient origin.

And there is even seemingly good reason to suspect that the echidnas and the platypus are derived from crosses between mammals and birds. Vickers and Williamson(in Margulis et al. 2011, Ch. 16, pp. 188-194) go so far as to list various probable interphylum crosses, which would be even more distant than any of the crosses just mentioned. And Zhang et al. (2014, p. 890) state that

And what do we have against all this evidence? Seemingly only a lot of preconceptions about what’s possible and what’s not.

As has already been mentioned, even today on the internet, one still encounters allegations that the okapi must be a giraffe-zebra hybrid. And not everyone agreed with Lankester even in his own day. As he later wrote (Lankester 1920, pp. 132-133), “A very eminent person whom I was conducting some years ago round the

For my own part, I’m suspicious of the dogmatic thinking I’ve encountered on this topic. It’s my hope that the matter will be investigated further and that we will eventually be able to determine the true nature of the okapi’s origins. For example, it would be interesting to see the results of repeated artificial insemination of female giraffes with zebra sperm, and vice versa. Genomic analysis would also be of interest.

Human origins: Are we hybrids? >>

By the same author: Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World, Oxford University Press (2006).

Most shared on Macroevolution.net:

Human Origins: Are we hybrids?

On the Origins of New Forms of Life

Mammalian Hybrids

Cat-rabbit Hybrids: Fact or fiction?

Famous Biologists

Dog-cow Hybrids

Georges Cuvier: A Biography

Prothero: A Rebuttal

Branches of Biology

Dog-fox Hybrids

Chicken-pigeon hybrids

Chicken-pigeon hybrids Cow-horse hybrids

Cow-horse hybrids Pig-human hybrids

Pig-human hybrids Cow-human hybrids

Cow-human hybrids