On the Origins of New Forms of Life

9.5: Gliriforms

EUGENE M. MCCARTHY, PHD GENETICS

|

|

(Continued from the previous page)

Nowak (1999: 1) says there are 4,809 mammalian forms treated as species that are either extant or that have existed within historical time (within the last 5,000 years). Of these, he says, 2,052 are rodents (Order Rodentia), and that an additional 81 are lagomorphs (rabbits, hares, or pikas). Taken together, animals of these two types are known as gliriforms.

Under orthodox theory, the origin of these animals is a complete mystery. The earliest fossils generally acknowledged as rodent date from the late Paleocene, the first epoch of the "Age of Mammals" (approx. 60 mya). These first rodents were already fully developed, according to Romer — that is, they already had all the skeletal and dental traits that distinguish their kind today. No earlier fossils have been accepted as rodent ancestors because (recall once again) all placental mammals, including rodents, are assumed to be descended from "small, primitive, generalized" placental mammals living in the late Cretaceous, whose descendants "radiated" into various "niches" left vacant by extinct dinosaurs.

|

|

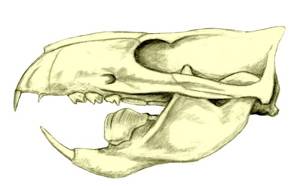

The skulls of gliriforms, such as this beaver's, are similar in many ways to those of multituberculates (see figure below). |

|

| Skull of the Paleocene multituberculate Ptilodus Credit: Nobu Tamura |

There were, however, rodentlike animals that greatly predate the late Cretaceous. These creatures existed long before, and survived to overlap the earliest acknowledged rodents. These animals were the multituberculates, whose name refers to the multiple tubercles on their rodentlike molars. They are well known from their common fossils. Paleontologist T. S. Kemp (1982: 287) says multituberculates were

The fossil record is replete with their remains. Multituberculates had already existed for some 100 million years when they were supposedly replaced by the first rodents. Most were the size of rats or mice — although some were as large as beavers — and many had incisors suitable for gnawing that were separated from masticatory molars by a gap, as in modern rodents. For example, Taeniolabis, is a large multituberculate known from the late Cretaceous to late Paleocene. Its skull and teeth are very similar to those of recent squirrels. Clemens and Kielan-Jaworowska (1979: 143) state that Taeniolabis'

Fossils of this organism lie on the same level with, or immediately below, strata containing the earliest fossils that have been called rodent.

Over the years a variety of investigators have suggested multituberculates are the ancestors of rodents, and of the related lagomorphs. Animals in these two groups are jointly known as gliriforms. But this proposal has never been accepted. Orthodox theory assumes multituberculates "branched off" from the "line" leading to modern mammals long before the accepted date for the first appearance of placental mammals (viz., it is assumed they were "prototherians"). In other words, conventional thinking asserts rodents and lagomorphs, which are placental mammals, could not possibly be derived from multituberculates, because

- The first multituberculates are known to predate the conventionally accepted date for the advent of the first placental mammal by many millions of years; and

- It is generally assumed the placental mode of reproduction did not arise among later multituberculates, but rather in a separate line of mammals.

The fact that such reasoning is widely accepted has an ironic sting. For while there is no clear fossil evidence to show early mammals were not placental, there are thousands of fossils showing multituberculates were similar to gliriforms. The extreme similarity between multituberculate teeth and those of rodents would be "superficial," as some authors suggest, rather than real only if we could be sure the multituberculates were not ancestral to acknowledged rodents and lagomorphs. But the superficiality of the similarity seems itself to be a phantasm when viewed in light of

- The observed similarity of multituberculate hard anatomy to that of recognized gliriforms;

- The absence of any other candidates for "gliriform ancestor";

- The implausibly abrupt advent of the earliest creatures officially designated as gliriforms (they already had at their earliest appearance all the traits characteristic of modern gliriforms); and

- The fact that the last fossils designated as "multituberculate" immediately precede and even somewhat overlap the first fossils designated as gliriform.

The numerous multituberculate forms known from fossils are easily pictured as giving rise to a wide variety of descendant gliriform types.

The claim that multituberculates independently evolved gliriform traits becomes even more suspect if we consider that a separate, but similar, claim has been made with respect to the notoungulates of South America. Biologists have long puzzled over the supposedly sudden appearance of rodents in South America (lower Oligocene of Patagonia). It is most peculiar, they say, that whole families of distinctively South American rodents should appear out of nowhere, on a previously rodentless continent that had at that time been isolated from other landmasses by ocean barriers for many millions of years. The controversy centers on whether these rodents "island hopped" from North America or "rafted" over from Africa.

If these ideas were correct, then the advent of South American rodents would indeed be a puzzling matter. But when the writer found paleontologists had ignored multituberculates as obvious rodent ancestors on other continents, he came to suspect that pre-Oligocene South American forms ancestral to modern rodents, too, might have been given a different name in order to make fossils fit accepted theory. An examination of South American fossils soon revealed earlier formations, of Paleocene and Eocene age (e.g., the Riochican, Casamayoran, and Mustersan), did contain types similar to rodents. But, again, paleontologists usually do not call them rodents. To call them rodents would be to assert they shared common ancestry with rodents of other continents. Any such assertion would carry with it the conclusion that the ancestors of South American rodents had already been present on that continent when it separated from Africa (prior to 105 mya). This conclusion would, as in the case of multituberculates, in turn imply rodentlike forms ancestral to modern rodents were already in existence at a date far too early to be consistent with accepted theory. Nevertheless, certain "notoungulate" families dating from earlier South American strata do contain gliriformlike animals, for instance forms in the family Interatheriidae. Dixon et al. (1988: 252) say that

In the same place they state that

In general, members of the notoungulate families Notostylopidae and Interatheriidae were rodentlike and those belonging to family Hegetotheriidae were rabbitlike. These forms are often called as "ungulates," but it appears that they for the most part had claws, not hooves.

The idea that multituberculates and certain notoungulates were actually early gliriforms is, again, consistent with the conclusion that placental mammals date back at least as far as the early Jurassic. Moreover, even if we consider only fossils officially accepted as gliriform (and ignore multituberculate and notoungulate fossils altogether), we would reach much the same conclusion — the temporal and geographic distribution of such fossils largely parallels that of the fossils discussed in previous sections (of primates, tamanduas, ankylosaur/armadillos, and stegosaurid/pangolins), and thus provides yet another line of evidence corroborating the early origin of placental mammals. True, many gliriforms can indeed swim and would therefore be able to pass narrow water barriers, unlike primates. But the idea of an ocean-going porcupine or rabbit closely approaches the realm of the impossible. Thus, with rodents and lagomorphs we seem to be reaching far back into the latter days of the synapsid era.

8.1: Dubious Assumptions - © Macroevolution.net