Centaurs (Human-horse Hybrids)

Antiquity

Mammalian Hybrids

Antiquity

This page was part of a draft for a chapter on this topic that has now been published in its finished form in my book Telenothians, which is available here.

|

Semiramis, so Juba informs us, was so much in love with a horse as to have had connection with it.

—Pliny the Elder, 8.64

|

Bronze man and centaur (Greek, mid-8th century B.C.) Enlarge

Bronze man and centaur (Greek, mid-8th century B.C.) Enlarge Pallas and the Centaur (Sandro Botticelli, 15th century) Enlarge

Pallas and the Centaur (Sandro Botticelli, 15th century) Enlarge

Scholars argue that the notion of centaurs originated with the ancient Greeks. The earliest known representation of such a creature, a terracotta statue, found at Lefkandi on the Greek island of Euboea, dates to about 1000 B.C. Homer, writing in the same era, also mentions centaurs. Another Greek representation of a centaur, dating to the mid-8th century B.C. is shown at right.

Among the Greeks and Romans, the notion of human-animal hybrids was widely accepted. In statuary and paintings, one of their gods, Pan, was regularly represented as human from the waist up, but as goat below. And he was considered a real being. For example, the Roman scholar and writer Marcus Terentius Varro (116–27 B.C.) claimed that Pan had once been the governor of Spain (see: Pliny 3.1). People actually believed that Zeus, the lord of the gods, had seduced women in various animal forms, including an eagle, a swan, a ram, a snake and a dolphin. It was said that as a bull, he had impregnated Europa and carried her away to Crete, where she gave birth to the Minotaur, half man, half bull. In another version of the story, Pasiphaë, the wife of King Minos of Crete, Europa’s son by Zeus, lusted after a white bull sent by Poseidon. Again, the Minotaur was the result. According to the Greek historian Apollodorus (Library, 2), the first centaur, Chiron, was born when the titan Kronos took on the form of a horse and made love to the nymph Philyra.

Titian, The Rape of Europa

Titian, The Rape of Europa

In fact, such behavior seems often to have been perceived in a sacred light. As Oliver Goldsmith put it, “fornication, incest, rape, and even bestiality, were sanctified by the amours of Jupiter, Pan, Mars, Venus and Apollo.” Thomas Mann went so far as to claim that “In the religions of antiquity, very often indeed, the sacred and the obscene were one.” To the Romans, says Salisbury (1994, p. 86),

Indeed, such connections, seemingly, were permissible even to mortals. For example, Pliny the Elder (The Natural History, 8.64) states, without condemnation, that Queen

And Suetonius, in his life of Julius Caesar, says,

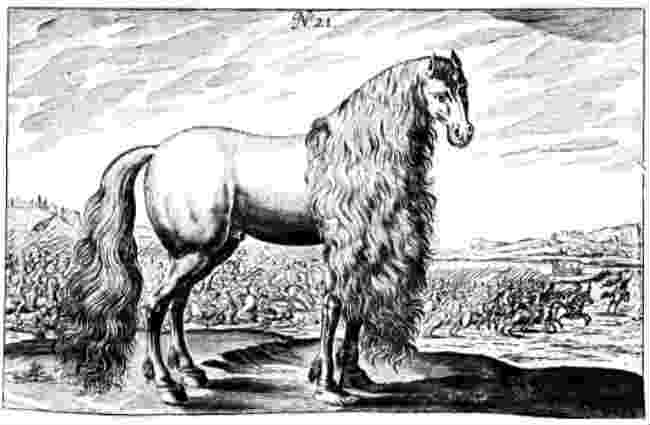

Julius Caesar’s human-footed horse as represented in Adlersflügel (1703, fig. 21). Compare to the description of the Cape Charles and Bloomingdale animals above. Regarding Caesar’s steed, Pliny the Elder (The Natural History, VIII, 64) states that “It is said, also, that Caesar, the Dictator, had a horse, which would allow no one to mount but himself, and that its forefeet were like those of a man; indeed it is thus represented in the statue before the temple of Venus Genetrix.”

Julius Caesar’s human-footed horse as represented in Adlersflügel (1703, fig. 21). Compare to the description of the Cape Charles and Bloomingdale animals above. Regarding Caesar’s steed, Pliny the Elder (The Natural History, VIII, 64) states that “It is said, also, that Caesar, the Dictator, had a horse, which would allow no one to mount but himself, and that its forefeet were like those of a man; indeed it is thus represented in the statue before the temple of Venus Genetrix.”

Indeed, in the antique mind, humans were close enough to horses that one might change into the other, as did Ocyroe the human daughter of Chiron. The Fates punished her for revealing the future by making her a mare. In the Metamorphoses (Book II), Ovid has her bemoan her fate:

to cast the future? Now my human form

puts on another shape, and the long grass

affords me needed nourishment. I want

to range the boundless plains and have become,

in image of my father’s kind, a mare:

but gaining this, why lose my human shape?

My father’s form is one of twain combined.

The early Christians, too, believed in centaurs. St. Jerome in The Life of Paulus the First Hermit (§7), states that St. Anthony in setting out in search of Paulus, came upon a centaur:

Female centaur. Detail from one of the Berthouville Centaur cups. Repoussé silver, Italy, middle 1st century AD. From the Berthouville treasure. Wikimedia).

Female centaur. Detail from one of the Berthouville Centaur cups. Repoussé silver, Italy, middle 1st century AD. From the Berthouville treasure. Wikimedia). Female centaur. (Berthouville treasure). Wikimedia).

Female centaur. (Berthouville treasure). Wikimedia). A male and a female centaur attacking an angel. The Centaur Door of the Hôtel d'Albiat, Montferrand, France (15th century) Wikimedia).

A male and a female centaur attacking an angel. The Centaur Door of the Hôtel d'Albiat, Montferrand, France (15th century) Wikimedia). Centaur Chiron paying homage to Pirithous (Pompeii, before 79 AD; digitally enhanced)

Centaur Chiron paying homage to Pirithous (Pompeii, before 79 AD; digitally enhanced)Enlarge image

Philostratus the Elder (Imagines, II.3), describes female centaurs and their lives:

You used to think that the race of centaurs sprang from trees and rocks or, by Zeus, just from mares—the mares which, men say, the son of Ixion covered, the man by whom the centaurs, though single creatures, came to have their double nature. But after all they had, as we see, mothers of the same stock and wives next and colts as their offspring and a most delightful home; for I think you would not grow weary of Pelion and the life there and its wind-nurtured growth of ash which furnishes spear-shafts that are straight and at the same time do not break at the spearhead. And its caves are most beautiful and the springs and the female centaurs beside them, like Naïads if we overlook the horse part of them, or like Amazons if we consider them along with their horse bodies; for the delicacy of their female form gains in strength when the horse is seen in union with it. Of the baby centaurs here some lie wrapped in swaddling clothes, some have discarded their swaddling clothes, some seem to be crying, some are happy and smile as they suck flowing breasts, some gambol beneath their mothers while others embrace them when they kneel down, and one is throwing a stone at his mother, for already he grows wanton. The bodies of the infants have not yet taken on their definite shape, seeing that abundant milk is still their nourishment, but some that already are leaping about show a little shagginess, and have sprouting mane and hoofs, though these are still tender.

How beautiful the female centaurs are, even where they are horses; for some grow out of white mares, others are attached to chestnut mares, and the coats of others are dappled, but they glisten like those of horses that are well cared for. There is also a white female centaur that grows out of a black mare, and the very opposition of the colours helps to produce the united beauty of the whole.

In his Cyropaedia (4.3.17-20), the Greek historian Xenophon quotes a Persian nobleman, Chrysantas:

Now the creature that I have envied most is, I think, the Centaur (if any such being ever existed), able to reason with a man’s intelligence and to manufacture with his hands what he needed, while he possessed the fleetness and strength of a horse so as to overtake whatever ran before him and to knock down whatever stood in his way. Well, all his advantages I combine in myself by becoming a horseman. At any rate, I shall be able to take forethought for everything with my human mind, I shall carry my weapons with my hands, I shall pursue with my horse and overthrow my opponent by the rush of my steed, but I shall not be bound fast to him in one growth, like the Centaurs. Indeed, my state will be better than being grown together in one piece; for, in my opinion at least, the Centaurs must have had difficulty in making use of many of the good things invented for man; and how could they have enjoyed many of the comforts natural to the horse? But if I learn to ride, I shall, when I am on horseback, do everything as the Centaur does, of course; but when I dismount, I shall dine and dress myself and sleep like other human beings; and so what else shall I be than a Centaur that can be taken apart and put together again?

Pliny the Elder (Naturalis Historia, VII, iii) tells of a centaur sent to Claudius Caesar (Roman emperor 41-54 A.D.) from Egypt preserved in honey and claims to have seen it himself. (Compare the satyr, reportedly also first seen in Egypt and sent to Emperor Constantine.) In the same place, Pliny mentions the birth of another centaur as if it were an historical event. It had been born in Saguntum, he says, in the year the city was destroyed by Hannibal (218 B.C.).

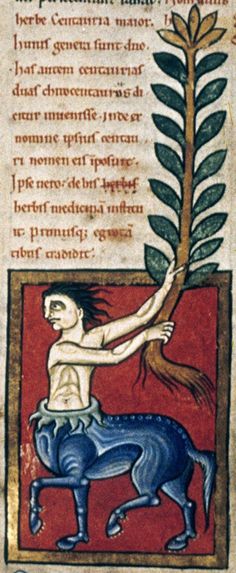

Centaur (Bodleian Library, MS. Ashmole 1462, Folio 23r).

Centaur (Bodleian Library, MS. Ashmole 1462, Folio 23r).

In his paradoxography, On Marvels (34-35), a later writer, Phlegon of Tralles wrote of an embalmed centaur in the imperial collection of the Emperor Hadrian (reigned 117-138 A.D.). He says this creature was originally sent to Emperor Claudius, so whatever this specimen might actually have been, it seems it was the same one mentioned by Pliny. It was known as the Centaur of Saune (a place in Arabia where it was supposedly caught). Phlegon, a literary freedman who served on Hadrian’s staff, says it had a face more fierce than a human’s, hairy arms and fingers, and a human torso that merged with a horse’s body and limbs. He says (see Hansen 1996, p. 49) other centaurs had been reported, but

Albertus Magnus

Albertus Magnusc. 1200-1280

Historian of biology Conway Zirkle (1941: 487) states that the existence of centaurs was accepted until late medieval times. He mentions the Byzantine scholar Manuel Philes (c. 1275-1345) as a proponent of this notion, and also cites the Roman Catholic saint Albertus Magnus (c. 1200-1280), quoting him as follows (De Animalibus, Bk. XXII, Tr. 2, Ch. 24):

But in truth, belief in centaurs persisted to a far later date than Zirkle suggests.

Modern era reports about centaurs >>

Onocentaurs

Onos is Greek for ass, so the name onocentaur means “ass-centaur.” Vincent of Beauvais (c. 1190-1264?) in his Speculum Naturale (Vol. II, Bk. 20, Ch. 97) states that

This, incidentally, is the form (ass’s head and human body) that Shakespeare’s bewitched weaver, Nick Bottom, takes on in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (see image below).

Edwin Henry Landseer, Scene from A Midsummer Night's Dream. Titania and Bottom (1848-1851)

Edwin Henry Landseer, Scene from A Midsummer Night's Dream. Titania and Bottom (1848-1851)

From Bullfinch’s Mythology:

“These monsters were represented as men from the head to the loins, while the rest of the body was that of a horse. The ancients were too fond of a horse to consider the union of his nature with man’s as forming a very degraded compound, and accordingly the Centaur is the only one of the fancied monsters of antiquity to which any good traits are assigned. The Centaurs were admitted to the companionship of man, and at the marriage of Pirithous with Hippodamia they were among the guests. At the feast of Eurytion, one of the Centaurs, becoming intoxicated with the wine, attempted to offer violence to the bride; the other Centaurs followed his example, and a dreadful conflict arose in which several of them were slain. This is the celebrated battle of the Lapiths and the Centaurs, a favorite subject with the sculptors and poets of antiquity.

“But not all the Centaurs were like the rude guests of Pirithous. Chiron was instructed by Apollo and Artemis, and was renowned for his skill in hunting, medicine, music, and the art of prophecy. The most distinguished heroes of Greek history were his pupils. Among the rest the infant Asklepios was intrusted to his charge by Apollo, his father. When the sage returned to his home bearing the infant, his daughter Ocyroe came forth to meet him, and at sight of the child burst forth into a prophetic strain (for she was a prophetess), foretelling the glory that he was to achieve. Asklepios when grown up became a renowned physician, and even in one instance succeeded in restoring the dead to life. Hades resented this, and Zeus, at his request, struck the bold physician with lightning, and killed him, but after his death received him into the number of the gods.

“Chiron was the wisest and most just of all the Centaurs, and at his death Zeus placed him among the stars as the constellation Sagittarius.”

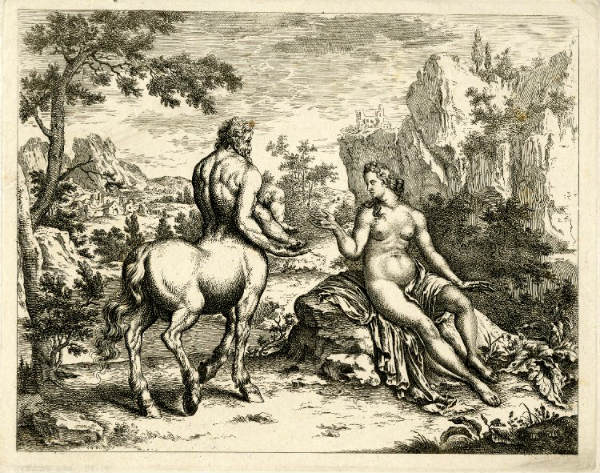

The centaur Chiron, showing the infant Asclepius to his daughter, the prophetess Ocyroe (etching, copy after Mieris, 1828).

The centaur Chiron, showing the infant Asclepius to his daughter, the prophetess Ocyroe (etching, copy after Mieris, 1828).

Hercules slaying the centaur Nessus, from The Labours of Hercules. Engraving, 1542. B. 97, p. 106, Holl. 99 ii/v. Artist: Sebald Beham (1500-1550).

Hercules slaying the centaur Nessus, from The Labours of Hercules. Engraving, 1542. B. 97, p. 106, Holl. 99 ii/v. Artist: Sebald Beham (1500-1550).

From Plutarch’s Banquet of Seven Wise Men

(Source)

“As Thales was talking after this fashion, in comes a servant and tells us it was Periander’s pleasure we would come in and inform him what we thought of a certain creature brought into his presence that instant, whether it were so born by chance or were a monster and omen; — himself seeming mightily affected and concerned, for he judged his sacrifice polluted by it. At the same time he walked before us into a certain house adjoining to his garden-wall, where we found a young beardless shepherd, tolerably handsome, who having opened a leathern bag produced and showed us a child born (as he averred) of a mare. His upper parts as far as his neck and his hands, was of human shape, and the rest of his body resembled a perfect horse; his cry was like that of a child newly born. As soon as Niloxenus saw it, he cried out, 'The gods deliver us!' and away he fled as one sadly affrighted. But Thales eyed the shepherd a considerable while, and then smiling (for it was his way to jeer me perpetually about my art) says he, I doubt not, Diocles, but you have been all this time seeking for some expiatory sacrifice, and meaning to call to your aid those gods whose province and work it is to avert evils from men, as if some great and grievous thing had happened. Why not? quoth I, for undoubtedly this prodigy portends sedition and war, and I fear the dire portents thereof may extend to myself, my wife, and my children, and prove all our ruin; since, before I have atoned for my former fault, the goddess gives us this second evidence and proof of her displeasure. Thales replied never a word, but laughing went out of the house. Periander, meeting him at the door, inquired what we thought of that creature; he dismissed me, and taking Periander by the hand, said, 'Whatsoever Diocles shall persuade you to do, do it at your best leisure; but I advise you either not to have such youthful men to keep your mares, or to give them leave to marry.'”

From Aelian’s De Natura Animalium 17:9

“Indeed, it is now in my mind to describe the onocentaur, relating the things I have learned through hearsay and fable. This onocentaur undoubtedly has a face similar to a man’s but surrounded by long hair. Its neck and chest also have a human appearance. It also has on its chest distended breasts. It has shoulders, arms, elbows and hands and a chest and even loins like a human’s. Its back, stomach, sides and hind legs are similar to those of an ass, and are ash colored as an ass, but the lower part of the stomach (over toward the side) is of a lighter shade. Its hands perform a double duty, for when there is need for speed, they run ahead of the hind feet and consequently cannot be overtaken by other four-footed animals. Moreover, when it finds it necessary to seize food or to raise, place, seize or bind anything, the hands, which formerly were feet, are brought forth and then it does not walk but sits. It is an animal of a serious, sad spirit, for, if it is captured, not enduring confinement, it refuses all food because of its desire for liberty and starves to death. Crates of Mysian Pergamon testifies that Pythagorus tells these things concerning the onocentaur.”

Most shared on Macroevolution.net:

Human Origins: Are we hybrids?

On the Origins of New Forms of Life

Mammalian Hybrids

Cat-rabbit Hybrids: Fact or fiction?

Famous Biologists

Dog-cow Hybrids

Prothero: A Rebuttal

Branches of Biology

Dog-fox Hybrids