The Hybrid Hypothesis

4: The Bipedal Ape

|

The Lord will give grace and glory. No good thing will he withhold from them that walk uprightly.

—Psalms, 84:11

|

|

Dear Gene,

I have been a lifelong admirer of Charles Darwin. I live only four miles from Down House, and even met my future wife there. I read your hybridisation theory of human evolution (with mounting guilt as I read on) while eating a bacon sandwich at my work desk. I must say that I think that the evidence you have gathered in support of your theory is, prima facie, pretty compelling. I personally believe that, in years to come, your point of view will become as mainstream in academic circles as Darwin's are currently. Hard evidence for the viability of disparate species hybrids will come. Until then I wish you every success in your excellent work. P.S. If you come to the UK we must meet. Best regards, yours sincerely, John P———

A poem sent in by the same reader (John P.):

Eugene's Testament (from the book of Hybridogenesis) The Lardon of Eden The weight of cogent argument seems reasonable to me, A theory that explains the way that people came to be, The distinct possibility, that open minds avow, That Adam was a chimpanzee and Eve a buxom sow. |

Plato's minimal definition of a human being as a "featherless biped" exploits the fact that it is unusual for a mammal to use only two feet in the course of normal locomotion. Since we're mammals, it's easy enough to understand the lack of feathers. Why, though, do we go about on two feet? Human bipedality has long been a subject of controversy. How long have human beings stood erect? How long did the transition take from quadrupedal locomotion to bipedality? What factors caused the change? Why have other primates not done the same?

Following in Darwin’s footsteps, a wide variety of authors have asserted that human beings gradually developed the ability to walk on two feet in response to selective pressures demanding that two hands be free to manipulate tools. In his book, The Ascent of Man, Darwin (1871) stated this view succinctly: "If it be an advantage to man to have his hands and arms free and to stand firmly on his feet, of which there can be little doubt from his pre-eminent success in

This explanation is not without its flaws. For one thing, should we conclude on the basis of our supposedly “pre-eminent success in the battle for life” that every human trait is superior? Isn’t this line of reasoning a bit vague and self-indulgent? Are our hands really in any way perfect—or do we just see ourselves that way? Isn’t it possible to “manufacture weapons” while sitting down?

And then, there is the presumption that we became “more and more erect or bipedal.” Fossil evidence does not confirm this gradual transition. Apparently, even very early hominids were fully bipedal. Thus, Lovejoy (1975, p. 323) observes that "for a number of years and throughout much of the literature there has been an a priori assumption that australopithecine locomotion and postcranial morphology were 'intermediate' between quadrupedalism and the bipedalism of modern man. There is no basis

Fossil footprints preserved in volcanic ash at Laetoli, Tanzania, indicate that hominids* were fully bipedal 3.7 million years ago (Clarke 1979; Leakey 1978; Tattersall 1995, p. 148). Similarly, Straus and Cave (1973) concluded that the posture of Neanderthals was not significantly different from that of modern humans. Homo erectus was also fully upright and bipedal (Milner 1990, p. 217). This lack of confirmation from the fossil record leaves gradualistic explanations of bipedalism standing on shaky ground.

@macroevo - I think I just became kosher. http://t.co/BebXbavhy7

— Bryan Goldstein (@brysgo) September 13, 2013

Even on a hypothetical level, the idea that early humans "gradually" attained erect posture is implausible. One must either go on all fours or stand erect. No feasible intermediate posture exists. Hollywood portrays cave men as slumped over, arms hanging down. Maintaining such a position for any length of time would put an extreme strain on the muscles of the lower back. Millions of years of slouching, then, would surely have produced more than a few backaches. In fact, it seems ridiculous to suggest that hominids went about day in, day out, partially erect. The physical strain would be too great, even for us with our supposedly better-balanced bodies. Gradualistic thought forces the conclusion that early "human beings" spent a portion of their time in the quadrupedal position, but spent a gradually increasing portion of time erect as evolution progressed. Why would there be such a trend? Why have we developed the ability to stand all day on two feet?

The many physical distinctions making a bipedal form of locomotion possible (even necessary, for efficiency) in humans would require many genetic alterations. Anyone who wishes to account for the spread of these mutations in terms of gradual evolution must show how bipedality increased our ability to survive and reproduce. Yet, a comparison of human and simian modes of locomotion, suggests bipedality does not appear to be any great boon. Supposedly, "the freeing of the hands" made tool manipulation possible. The need for such manipulation, in turn, is said to have necessitated enlargement of the brain.†

But why must a tool maker or a tool user stand erect for long periods of time? The hand, not the spine, seems to be the essential element in most manipulative processes. Few such activities would require anything more than the facultative bipedality of an ape. A chimp's hands would serve as well as ours in fashioning a spear, bow, or axe—they might even serve better: a chimpanzee has four hands. Human beings commonly sit down to work on such projects, having no need to stand. I can easily picture chimpanzees doing the same—chipping away at an arrowhead or heating spear tips in a fire. Studies of these animals have documented that their hands, too, are capable of performing subtle tasks such as decanting a glass of wine (Keith 1899, p. 298) or even threading a needle (Dart and Craig 1959, p. 109). Surely, their using rocks and sticks to crack nuts (Struhsaker and Hunkeler 1971) is not so different from the way our forebears would have used hand axes.

Kortlandt (1967) has shown that chimps are capable of using weapons when they choose to do so. In his experiments, he presented various objects to wild chimpanzees and recorded their reactions. In one test, he placed a stuffed leopard on the ground near a troop of chimpanzees. The "leopard" clutched a facsimile baby chimp in its paws, and a concealed tape recorder emitted baby cries. Presented with this phenomenon, the apes attacked, using large broken branches as clubs. Kortlandt says that the blows were of such force that, had the leopard been real, it would surely have been killed. Apparently we are not the only ones with "free" hands.

Jane Goodall has documented "aimed rock throwing" behavior in free-living chimpanzees (Goodall 1983, p. 277; van Lawick-Goodall 1964). If they can carry clubs and throw rocks, then chimpanzees certainly have the anatomical wherewithal to carry and throw a spear.

Physically, chimps may be better equipped for throwing than we are. Their arms are far stronger than those of human beings—about four times as strong, according to van Lawick.† Our ancestors invented the spear thrower, a hooked stick that, in effect, lengthens the arm, increasing the force of the throw. The arms of chimpanzees are already longer and stronger than those of humans.

If they can carry clubs, apes should also be physically capable of stalking prey with a spear. Human hunters do not stand erect when their quarry is nearby. Rather, they crouch, or even crawl, and approach their prey from downwind, taking advantage of available cover. Only at the last moment when the prey is in range do they spring up and throw the spear. Chimpanzees are quite capable of leaping and throwing an object simultaneously (Goodall 1983, p. 210, p. 277, and 4th photo after p. 234).

For all of these reasons, then, it is at least questionable whether bipedality has enhanced our ability to survive and reproduce. A gradualist would object that, even if we do not understand the selective pressures involved, such pressures must, nevertheless, have existed, and that humans otherwise would never have made the transition to erect posture. But slow selection of minute mutations is not the sole conceivable mechanism that can account for human bipedality.

An Analysis of Human Bipedality

If we listed all the features contributing to our upright mode of locomotion, we would find some of those features in the chimpanzee. Nevertheless, even though chimpanzees do walk on two feet from time to time, such is not their normal mode of progression. They lack certain characteristics that make moving around on the hind limbs not only convenient for human beings, but really, under most circumstances, the only practical way of getting around. But what if pigs possessed all of those features relevant to bipedality that apes lack. Wouldn't it then be easy to understand why a pig-ape hybrid might walk on two feet?

All the human distinctions listed in the remainder of this section were first identified by other writers; I've merely gathered them together. If a scholar somewhere has claimed that a certain characteristic distinguishes human beings from chimpanzees and that that feature contributes to bipedality, then — if I have encountered the claim — I at least mention it. I exclude only those features that relate to the skull; cranial features are discussed in the next section. (It will also be convenient in this section to discuss a few skeletal distinctions of human beings not directly relating to bipedality.)

In the literature, most features said to contribute to human bipedality are located in the spine and lower extremities. For example, our gluteal muscles, large in comparison to those of other primates,† enhance our ability to hold our torso erect. Ardrey (1969, p. 260) observes that

Certainly, the gluteus maximus is a significant portion of our anatomy. But, did apes "fail" to alter their bodies in this respect? Or did they simply lack the potential for doing so? Perhaps no pure primate had the potential to evolve into a human being by gradual mutation alone. We could, however, have obtained our big rump by other means. One has only to think of a country ham to realize that pigs, too, have powerful buttocks. Perhaps the very first hominid had a large rump as well as many other distinctively human features.

The Spinal Column

Centralization of the spine, another factor facilitating our erect carriage, is not seen in other primates to the extent that it is in humans (Schultz 1936, p. 442). With the spine shifted toward the center of the body, a larger proportion of the trunk lies to its rear. As a result, the anterior portion is better counterbalanced by the posterior and less effort is required to keep the body erect. In pigs, the spine is more centralized even than our own (Dyce et al. 1987, p. 742, fig. 35-2 & 35-3), just as ours is more centralized than an ape's.

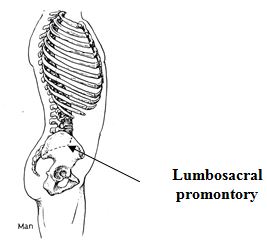

Centralization of the vertebral column by itself, however, does not account for the ease with which the human body is held erect. Many other modifications of the spine facilitate our bipedality. At the base of the human spine, where the lumbar vertebrae meet the sacrum, is a sharp backward bend known as the lumbo-sacral promontory (see illustration below). The angle formed by this promontory is more acute on the front side of the spine because of subsequent tapering of the sacrum. This configuration causes the sacrum to form the roof of the pelvic cavity in human beings, instead of the rear wall as it does in other primates (Schultz 1950, p. 442).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

More significantly, it brings the base of the flexible portion of the spinal column into a position directly above the hip joints (when viewed from the side). The force applied to the pelvis by the weight of the upper body is directed straight downward through the hip joints and does not tend to rotate the pelvis around those joints. When an ape is fully erect, a vertical line passing through the base of the spine falls behind the hip joints so that a rearward twisting torque is applied to the pelvis. This torque must be countered by constant muscular exertion.

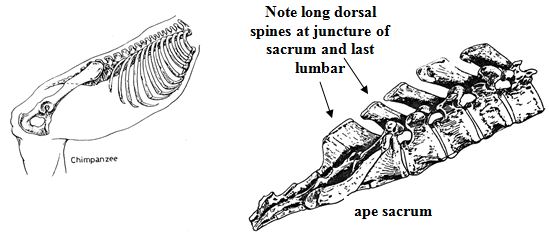

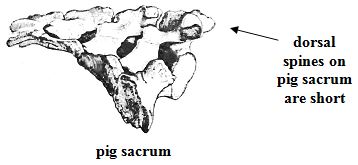

The dorsal, backward-projecting spine of the uppermost vertebra on an ape sacrum is too long to permit backward flexure of the lowermost lumbar. In human and pig,the spines on the dorsal (back) face of the sacrum are quite short and do not interfere with bending at this point (see illustrations above). But, do pigs have a lumbo-sacral promontory? In anatomical depictions of pig skeletons arranged in the typical quadrupedal pose, no promontory is visible. But if a human being gets down on all fours, then the lumbar region is twisted forward relative to the sacrum, and the promontory disappears. Perhaps an erect pig would also develop a sharp bend at the base of the spine. Obviously, pigs do not ordinarily stand upright, and I have never seen a drawing showing the configuration of a pig skeleton in such a position. Nevertheless, anyone willing to examine a hanging side of pork will see that a lumbo-sacral promontory is evident. Hanging a halved carcass by the hind leg causes the leg to swing into a position that closely approximates erect human posture. Here, again, porcine anatomy accounts for a human peculiarity.

The human spine contains more lumbar vertebrae and fewer sacral vertebrae than does the spinal column of any great ape (Schultz 1950, p. 439). Because sacrals are fused and lumbars are not, the human spine is much more flexible than an ape's. Consequently, we are capable of bending the body backward until it balances over the hip joints (without rotating the pelvis backward). The "small" of the human back is the external evidence of this backward curvature of the lumbars. Pigs have even fewer sacrals (Barone 1968, vol. I, p. 439) than do human beings, and they have more lumbars (Sisson and Grossman 1953, pp. 162 & 166). So here, again, humans are intermediate between apes and pigs.

In all the great apes, the cervical (neck) vertebrae have long dorsal spines — significantly longer than those on their thoracic (ribbed) vertebrae (Duckworth 1915, p. 174; Schultz 1961, IV, 5, p.31, fig. 7; 1968, p. 154, fig. 7-19; Straus and Cave 1973, p. 223). So the human neck allows a much wider arc of nodding motion than what is seen in apes (Schultz 1968, p. 154; Sonntag 1923, p. 421).*

Though all cervical spines are long in apes, the fourth and fifth are usually longer than the sixth and seventh. Humans and pigs, on the other hand, have relatively short cervical spines except on the seventh cervical, where the spine is long, but not so long as the thoracic spines (Barone 1968, I, p. 40; Dixson 1981, p. 47, fig. 23). As a result, humans are better able than apes to adjust the balance of the head by tilting it backward to the equilibrium point. Moreover, the figures above clearly show that human cervicals are generally more similar to a pig's than to those of an ape.†

The seventh human cervical vertebra differs in another respect from those of other primates: it has transverse foramens or "foramina" (see illustration below). These large openings on either side of the spinal canal "are very rarely missing in even the seventh vertebra of Homo sapiens, but in the other primates it is rare to find corresponding foramina in this segment" (Schultz 1973). In a work on the comparative anatomy of humans and domestic animals, Barone (1968, vol. I, p. 391) discusses the seventh vertebra, saying it "is not, in general, pierced by a transverse foramen, with the exception of pigs and human beings. In these two cases it always is."

Pelvis and Coccyx

At the opposite end of the spine are the coccygeal vertebrae which together form the coccyx, or tail bone. Adolph Schultz (1969, p. 77) observes that these vertebrae are fused in chimpanzees, a lack of flexibility he terms "puzzling." Under the assumption that humans stand on a "higher" rung of the evolutionary ladder, chimpanzees should have a longer and more pliable "tail" than do humans. But, in fact, the human coccyx is not fused, but movable — especially in females, where it bends backward when they are giving birth (Gray 1959, p. 267).

The human pelvis and birth canal are smaller than those of apes (Dixson 1981, p. 155, Fig. 48). Moreover, the sacrum and coccyx curve inward in humans to make a sharp-pointed obstacle that must be negotiated by an emerging infant (Gray 1959, p. 267). In apes there is no curvature (see illustration above), which leaves the birth canal unobstructed (Duckworth 1915, p. 175, Fig. 118; Schultz 1969, p. 76, Fig. 13). With their constricted birth canals, human females experience far more difficulty in delivery than do their simian counterparts. "Parturition in the great apes is normally a rapid process," according to primatologist A. F. Dixson, who further states that

Turning of the head occurs in Homo sapiens because, unlike other primates, the pelvis is so short that the birth canal is wider than it is high (Dixson 1981, p.155, Fig. 48). In humans, the height (antero-posterior diameter) of the birth canal depends on the length of the coccyx and, specifically, on how closely the tip of the coccyx approaches the front wall of the passage.

The human coccyx, then, ought to be relatively short, since the human neonate is larger than any newborn ape. And yet, "man is distinct among higher primates by possessing the largest average number of coccygeal vertebrae, i.e., by having been so far affected least by the evolutionary trend to reduce the tail" (Schultz 1950, p. 438). "In the human coccyx there may be as many as six elements, in the anthropoids there are quite commonly only two. The anthropoids have gone further than man in the reduction of the tail" (Jones 1929). This longer "tail" is difficult to account for in terms of natural selection. With respect to reproduction, it is clearly a negative factor. Nor does it have any evident utility in other respects. Perhaps we should look elsewhere for an explanation. The sacrum of a pig is curved on its inner side much like that of a human being (see illustration above). Obviously, pigs have tails, albeit short ones. If Homo is a hybrid of ape and pig, we expect the human sacrum to be curved and the coccyx to be longer and more flexible than an ape's. The human pelvis is peculiar in many respects. According to Adolph Schultz,

The most obvious difference is the shortness of the human ilium. The pelvis of an ape is about half again as long as a human's, as a percentage of body length, and closely approaches the last rib (Kurtén 1972, p. 21; Schultz 1950, p. 438, fig. 6 & p. 439, Table 6). And Schultz (1969, p. 76) notes specifically that the iliac crest approaches the last ribs "far more closely than in any other primates"). A pig has a short pelvis and a wide gap between pelvis and rib cage, just as we do. The upper blades of the pelvis run from side to side in apes but turn towards the front in humans (Kurtén 1972, p. 21). They also turn forward in pigs (Nickel et al. 1954, vol. I).

Human tail

Rarely, human babies are born with tails. The following is from an abstract of a paper (Dao and Netsky 1984) reviewing this phenomenon: "The true, or persistent, vestigial tail of humans arises from the most distal remnant of the embryonic tail. It contains adipose and connective tissue, central bundles of striated muscle, blood vessels, and nerves and is covered by skin. Bone, cartilage, notochord, and spinal cord are lacking. The true tail arises by retention of structures found normally in fetal development. It may be as long as 13 cm [5 in.], can move and contract, and occurs twice as often in males as in females. A true tail is easily removed surgically, without residual effects. It is rarely familial. Pseudotails are varied lesions having in common a lumbosacral protrusion and a superficial resemblance to persistent vestigial tails. The most frequent cause of a pseudotail in a series of ten cases obtained from the literature was an anomalous prolongation of the coccygeal vertebrae."

Lower Extremities

All nonhuman catarrhine primates have longer arms than legs (Schultz 1950, p. 434; 1968, p. 130). The reverse is the case in humans. But pigs, like humans, have longer hind limbs than forelimbs (Barone 1968, p. 1175). The femur (thighbone) is the largest bone of the body. Paleoanthropologists distinguish the femur of a hominid from an ape's in several ways. On the front of the lower end of the femur in humans and apes, the patellar groove forms a track for the kneecap. In apes, this groove is relatively shallow and its medial lip is more prominent than the lateral (Lovejoy 1975, pp. 309-310; Preuschoft 1970, p. 282). But in humans (ibid.), and in pigs (Barone 1968, vol. I, p. 693), this groove is deep and the lateral lip is the more elevated of the two.

Also, on the distal (lower) end of the femur are two condyles. In Homo, these condyles are of approximately equal size. In pongids the medial one is markedly larger than the lateral (Preuschoft 1970, p. 282), but in pigs the femoral condyles are almost exactly equal in size (Barone 1968, vol. I, pp. 690, 693). Human femoral condyles also differ in shape from those of other primates. "In hominids, both condyles show a distinct elliptical shape, indicating a specialization for maximum cartilage contact in the knee joint only during full extension of the lower limb. In [primate] quadrupeds, on the other hand, the condyles show no such specialization to one position, being essentially circular in cross-sectional outline" (Lovejoy 1975, p. 308). Nevertheless, many non-primate quadrupeds do, in fact, have elliptical femoral condyles. Among them are most of the domestic animals: cows, sheep, horses, dogs — and pigs (Nickel et al. 1954, vol. I, p. 88, Abb. 168-173; see illustration below). We have no reason, then, to think that human elliptical condyles represent an adaptation aiding in bipedal locomotion.

Quadrupedal primates are bowlegged, especially the anthropoid apes (Preuschoft 1970, p. 281). Human beings, however, are typically knock-kneed (ibid., Kurtén 1972, pp. 22-23). Preuschoft (ibid.) follows Kummer (1959; 1965) in suggesting that our knock-kneed stance is an adaptation facilitating bipedal posture, and bowlegs, to quadrupedal posture. But the domestic quadrupeds (dog, horse, cow, pig, etc.) are consistently knock-kneed.

In pigs, and most other domestic animals, the femoral condyles rest on crescentic menisci that are connected to the tibia (shinbone) in the same way as in humans (Nickel et al. 1954, vol. I, p. 214). This configuration is significant because, as Tardieu (Tardieu 1984, p. 183) points out, Homo sapiens is the only primate having a "crescent-shaped [lateral] meniscus with two tibial insertions" (see also: Aiello and Dean. 1990, p. 489; Duckworth 1915, p. 117 and Fig. 119; de Fenis 1918; Le Minor 1990; Retterer 1907; Sonntag 1924, p. 157; Vallois 1914). In fact, in the vast majority of catarrhine primates, including the chimpanzee and gorilla, the lateral meniscus is ring-shaped. In the tibia itself the most prominent difference is the presence of a long malleolus medialis in nonhuman primates (Swindler and Wood 1973, Plate 24). In Homo this downwardly directed, spike-like process is reduced to little more than a nub. In pigs it is so short as to be nearly nonexistent (Barone 1968, vol. I, p. 716).

We find another human distinction in the foot, in the joint between the heel bone (calcaneus) and the anklebone (astragalus). Szalay and Delson (1979, p. 495) note that one feature distinguishing hominids from apes is the "loss of [the] ancestral helical astragalo-calcaneal articulation, reducing the possible range of movements in this joint." In apes the articulation is "helical" because the joint allows rotation of the foot in a plane parallel to the ground. In Homo sapiens, this joint is more like a hinge. It allows only flexion and extension (Morris 1953, p. 386). A pig, too, has a hinge-type articulation between the calcaneus and the astragalus.

The proportions of the human foot are also peculiar for a primate. Duckworth (1915, p. 177) notes that the human heel bone is longer than that of apes. Baba (1985, pp. 183-186) found that the length of the third metatarsal bone exceeded the length of the calcaneus in all primates in his survey — except in humans, in which the calcaneus is slightly longer(the third metatarsal connects the middle toe with the ankle and composes most of the length of the foot between the ankle and ball of the foot). Our high ratio of calcaneus to metatarsal makes it easier for us to bear the body's weight on the ball of the foot (as we do each time we take a normal step), because the forepart of the foot and the heel bone can be thought of as two ends of a lever having the ankle as a fulcrum. As in humans, the heel bone is a bit longer than the third metatarsal in domestic pigs (Barone 1968, vol. I, p. 737).

Our fingers and toes are short, compared to those of apes (Romer 1966, p. 225). Our metacarpal bones and phalanges are shorter than a chimpanzee's, not just in relation to the overall length of the hand, but absolutely (Susman 1979, tables 5 & 6). This shortening can be explained by referring to the anatomy of pigs: their digits are even shorter and stubbier, than our own (which, of course, is the case for most quadrupeds).

Lastly, consider the ungual tuberosities. These small, hoof-shaped processes tip the bones (nail phalanges) that underlie the nails of our fingers and toes (see illustration below). Nonhuman primates do not have such processes. "When comparing the nail phalanges of apes to those of man, a pronounced slenderness of the former can be observed. If the impressive strength of pongid hands is taken into consideration, this is surprising" (Preuschoft 1973, p. 45). Shrewsbury and Johnson (1983, p. 475; see also Susman 1979, p. 226) state that "the distinguishing features of the human distal phalanx are the broad spade-like tuberosity with proximal projecting spine and the wide diaphysis, which is concave palmarly to create an ungual fossa. These features are not seen in primates such as the monkey and gorilla." This distinction, which was also present in the various extinct hominids (Musgrave 1971, pp. 539, 541), has been explained as an adaptation facilitating the manipulation of objects with the fingertips. If such is the case, why should these processes also be found on the tips of our toes? Do these hoof-like ungual tuberosities actually reflect a relationship between humans and ungulates like the pig? That is, are they vestiges of ancestral hooves?

Convergence or Relationship?

Our hypotheses have accounted for a number of traits in Homo. From the standard neo-Darwinian perspective, it is hard to understand why the parallels between human being and pig should be so extensive. Biologists call the existence of similar traits in animals that they consider to be distantly related analogy. They say analogy is found when animals live under similar conditions or have similar habits. The same needs in each case are supposed to cause structures of similar function to develop during the course of evolution. But when the organisms under consideration are considered to be closely related, such features are termed homologous. Homologous features are usually judged to be so when the similarities are numerous and extend to detail. As Dobzhansky et al. (1977, p. 270) put it, "Examination of the structure of convergent features usually makes it possible to detect analogy because resemblance rarely extends into the fine details of complex traits."

In this section we have considered one complex trait (bipedality) in a fair amount of detail. Any attempt to account for these details in terms of natural selection seems inadequate. It is difficult to see what “selective pressures” could have caused human beings and pigs to “converge” in so many different respects. Under neo-Darwinian theory, to explain most of the human features that we have just discussed, we have to posit pressures selecting for bipedality (some human features — long tail bone and ungual tuberosities — cannot be explained in this way). But pigs are quadrupeds. How will we account for the fact that they, too, have these features? Perhaps it is all just a coincidence, but after a certain point coincidence begins to assume the color of relationship.