Jean-Baptiste Lamarck

Biography

EUGENE M. MCCARTHY, PHD

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck(1744-1829)

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744-1829). French naturalist and soldier. Chief founder of the field of invertebrate paleontology. Early evolutionary theorist.

Lamarck was born on August 1, 1744 in the small town of Bazentin in northern France, the scion of an impoverished aristocratic family. He served in the military during the Seven Years War and, at the age of only 17, was awarded a commission for bravery in recognition of his actions on the battlefield. It was at this point that Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet (Lamarck’s given name) became the Chevalier de Lamarck, or Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, the name by which he was thereafter known.

Later, when Lamarck retired injured, he took up a new career in natural history. He first studied botany under the naturalist Bernard de Jussieu. The eventual product of this ten-year period of research was Lamarck’s Flore françoise (1778), a three-volume work on the plant life of France that brought its author into the front rank of French naturalists.

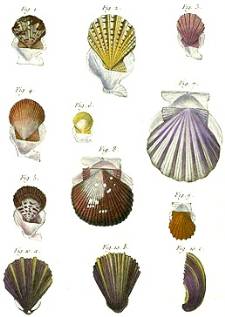

Scallops from Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique des trois règnes de la nature, 1782-1832.

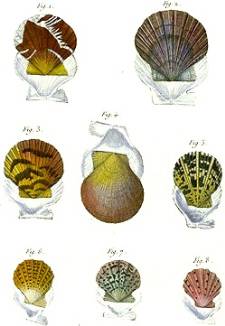

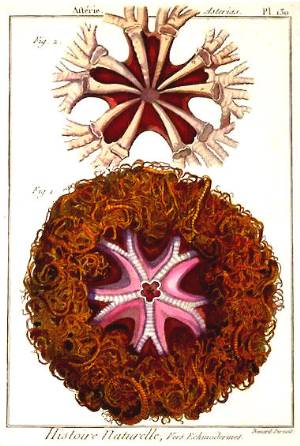

Scallops from Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique des trois règnes de la nature, 1782-1832. Starfish from Lamarck’s Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique des trois règnes de la nature, 1782-1832.

Starfish from Lamarck’s Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique des trois règnes de la nature, 1782-1832.

Lamarck eventually obtained a position at the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, and later at the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle where he became a professor of zoology. In 1801, he published Système des Animaux sans Vertebres, a landmark in invertebrate taxonomy. It was he who originated the distinction between vertebrates and invertebrates, and who introduced many still-existing major divisions of the latter category, such as crustaceans, arachnids and annelids.

Lamarck’s theory of evolution. Lamarck is now best remembered for his proposals concerning evolution. He was the first scientist to formally propose a gradualistic theory of evolution (as opposed to saltationist theories of evolution such as that proposed earlier by Linnaeus). As Darwin (Origin, 3rd ed., p. xiii) put it, “Lamarck was the first man whose conclusions on this subject excited much attention. This justly-celebrated naturalist first published his views in 1801, and he much

In his theory, Lamarck assumed that simple microscopic forms of life continuously arise spontaneously from nonliving matter. This notion that spontaneous generation occurs on an ongoing basis was still widely accepted in his day. But he further supposed that such forms had an innate tendency gradually to evolve over time into organisms of ever greater complexity. This was something no one else had said. Thus in 1803, he comments, “Do we not therefore see that through the action of the laws of organization ... nature has in favorable times, places, and

Contemporaries of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck: |

Under Lamarck’s theory, traits could arise, or become more developed, through the use of an organ or portion of the body. For example, he said the necks of giraffes had gotten longer as they were used to stretch ever higher for leaves. Traits could also diminish, he claimed, through “disuse.” In this way any organ that went unused would tend to shrink with the passing generations. For example, he said blind cave fish had become blind because their ancestors had not used their eyes.

This notion, that traits acquired in an individual’s lifetime in response to exercise or environmental stimuli could be passed on to descendant generations, was not new. In those days, many people, even scientists, thought acquired traits could be inherited (indeed, that very school of thought, despite its long being out of intellectual fashion, is again garnering adherents today).

But many other scientists opposed the idea, most prominently Cuvier. They ridiculed the idea with farcical scenarios such as cowboys fathering bowlegged babies or weight lifters producing muscle-bound children. However, many naturalists freely embraced the idea, including Darwin himself. For example, in the Origin (1859, pp. 479-480) he asserts that “Disuse, aided sometimes by natural selection, will

But Lamarck did not consider the inheritance of acquired traits crucial to his theory. The essential idea was an ongoing transformation of forms tending toward ever higher levels of complexity under the influence of natural laws.

He originated the idea of arranging organisms into genealogical trees of descent. As Locy (1915, pp. 131-132) notes, Lamarck “was the first to employ a genealogical tree and to break up the serial arrangement of animal forms. In 1809, in the second

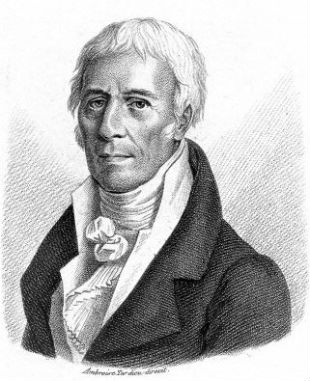

Lamarck (circa 1802)

Lamarck (circa 1802)

It is perhaps no coincidence that a former soldier, decorated for courage on the field of battle, was also the first scientist to suggest explicitly that human beings had evolved from apes (Philosophie Zoologique, 1809): “Certainly, if some race of apes, especially the most perfect among them, lost, by necessity of circumstances, or some other

Perhaps he was a bit too courageous — his free tongue made him enemies among the very men who could have promoted his career. Jean-Baptiste Lamarck died in penury and ended in a rented grave. His remains were later exhumed when the five-year lease expired, and their ultimate destination is now unknown.

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck - Biography - © Macroevolution.net

Major works of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck: Flore françoise (1778); Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique des trois règnes de la nature (1782-1832); Système des Animaux sans vertèbres (1801); Recherches sur l’organisation des corps vivants (1802); Philosophie Zoologique (1809); Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres (1815-1822).

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s exact dates of birth and death: Born: Aug. 1, 1744. Died: Dec. 18, 1829, aged 85.

Full Name: Though remembered as Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, his full name was actually Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, Chevalier de la Marck. As author, his name often appears as Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck. The standard abbreviation Lam. is used to indicate Jean-Baptiste Lamarck as author when citing a scientific name.

Cited work: Locy, W. A. 1915. Biology and its makers. New York: Henry Hold.

Most shared on Macroevolution.net:

Human Origins: Are we hybrids?

On the Origins of New Forms of Life

Mammalian Hybrids

Cat-rabbit Hybrids: Fact or fiction?

Famous Biologists

Dog-cow Hybrids

Prothero: A Rebuttal

Branches of Biology

Dog-fox Hybrids