Mules (Donkey × Horse)

Equus asinus × Equus caballus

Mammalian Hybrids

EUGENE M. MCCARTHY, PHD GENETICS, ΦΒΚ

|

Yet mules generate but rarely, even if they mate with their own or a close species.

—St. Albertus Magnus, De animalibus

|

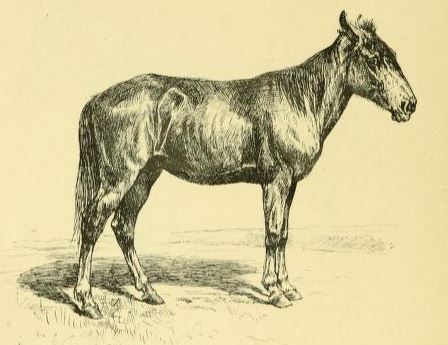

Enlarge

EnlargeA mule (horse × donkey)

The animal produced by crossing a male donkey (that is, a jackass or jack) and a female horse (a mare) is called a mule. The product of the reciprocal cross (stallion × jennet) is a hinny. Hinnies have always been less commonly produced. But Allen and Short (1997, p. 385) say, “We still lack conclusive proof as to whether there is any consistent phenotypic difference between mules and hinnies.”

The fact that few definite differences have been recognized is not surprising given that female mules and hinnies have an identical chromosome complement and differ genetically only with respect to the source of their mitochondrial DNA, which represents only a minuscule fraction of an animal’s DNA and thus would be expected to have a nearly undetectable effect on phenotype. In male hybrids the only additional difference is with respect to their sex chromosomes (“Chromosome X” and “Chromosome Y”). Male mules have a horse Y, a donkey X, and donkey mtDNA), whereas hinny males have the reverse, which would seem to reduce potential differences to a minimum.

However, rates of conception are much lower when stallions inseminate jennets, a fact that in itself may explain why breeders rarely try to produce hinnies. There is also a greater size disparity between a stallion and a jenny than between a jackass and a mare, a difference that probably also has favored the production of mules, given that it interferes with the physical act of mating.

One method that can be used to distinguish hinnies from mules, without genetic testing, is behavioral. A hinny, when given a choice, will usually prefer to herd with donkeys because its mother was a donkey, whereas the reverse is true for a mule. In fact, not only mules and hinnies, but also hybrids of all types typically choose to associate, and mate with, animals of their mother’s kind.

Moreover, difficult delivery (“dystocia”) is more common with jennets, even when pregnant with a pure donkey fetus. Jennets have a longer cervix than mares and it is also smaller in diameter, which may be part of the reason for these problems. And this incapacity may be aggravated by a phenomenon seen in many different types of mammalian crosses, that is, hybrids tend to grow too large for the womb when the smaller parent, in this case the jennet, serves as the mother.

Article continues below

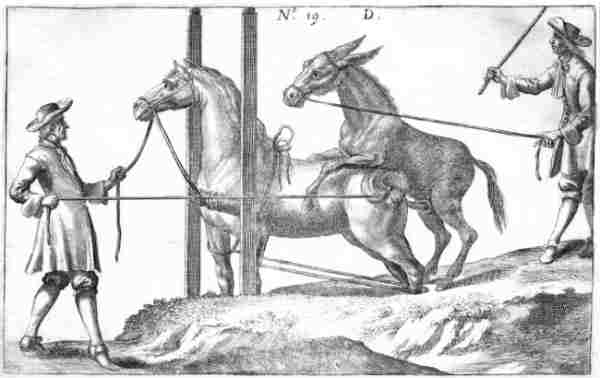

A hinny (source: Simonoff and Moerder, Les races chevalines, Paris).

A hinny (source: Simonoff and Moerder, Les races chevalines, Paris).

Jacks are specially raised for the production of mules. They are given, when still young colts, to nurse from a mare. In this way, they are imprinted on mares when they reach maturity and willingly mate with them. This practice is of long standing. The ancient Roman writer Varro (De re rustica, 81) comments,

Mules resemble donkeys, but are larger and stronger. They also eat cheaper food and have more stamina than a horse of the same size. They also have tougher hooves than horses, which makes them better suited to carrying burdens over rough terrain.

For these reasons, mules have been bred for at least 5,000 years (Allen and Short 1997, p. 385). They were used as beasts of burden in Egypt’s Old Kingdom (3rd millennium BCE), long before camels were used. And Zheng (1985) states that, according to historical records, mules were considered “treasures” in China 4,000 years ago. They are mentioned in the Iliad, in the Odyssey, and in Hesiod’s Works and Days (c. 900 BCE), as well as in the Hebrew Scriptures, although the Hebrews purchased all of their mules from non-Jews since Mosaic law expressly banned the production of hybrids. Indeed, the Jews believed it was people living before the Deluge (the "people of the generation of the flood") that had brought it on by permitting hybridization. This is clearly stated in the Jewish tractate Sanhedrin† (106b):

Jews were, however, allowed to raise mules: “It is permitted to raise mixed-species animals; it is only prohibited to crossbreed such animals” (Kilayim 8:1).

Apparently mules also occurred in the wild during Biblical times since it’s mentioned in Genesis (36:24) that Anah “found the mules in the wilderness, as he fed the asses of Zibeon his father,” though such references may in fact refer to onagers (Zirkle 1935).

Article continues below

Mule breeding. The mare stands in a pit to assist the jack in mounting (source: Adlersflügel 1703).

Mule breeding. The mare stands in a pit to assist the jack in mounting (source: Adlersflügel 1703).

Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) discussed mules extensively, mostly from a theoretical standpoint, in an attempt to account for their extreme sterility (mules, especially males, are unusually sterile in comparison with other, more fertile types of hybrids). Zirkle (1935, p. 7) says that the sterility of the mule made it the first animal whose hybrid origin was generally recognized because “the origin of fertile hybrids could easily be forgotten, particularly the origin of those which appeared before the dawn of history.” The mule, however, was so sterile that it was necessary to produce it with the original cross (Zirkle provides extensive information on the early history of mule). Early naturalists (e.g., Prichard 1836, p. 140) believed mules foaled more frequently in warmer climes.

The fact that the hybrid origin of the mule has so long been known, together with its marked sterility, has no doubt greatly contributed to the widespread, but erroneous, belief that hybrids of all types are sterile. In fact, hybrids produced from many types of crosses can produce offspring.

Perhaps no other hybrid is so familiar to the general public. Mules have even given rise to common words and popular sayings (e.g., “mulish,” “mule-headed,” “stubborn as a mule,” etc.). The Romans would say, “when a mule foals” (cum mula peperit) when they considered something very unlikely or impossible.

Sestertius of Galba

(68-69 A.D.)

In fact, the ancients viewed those rare cases when these animals did in fact produce offspring as portentous miracles. For example, according to Suetonius, when one of his mules became pregnant, the Roman politician Servius Sulpicius Galba took it as a sign that he would become emperor. The passage in question (Life of Galba, v, 48) reads, “An eagle snatched the intestines of the victim from the hand of Galba’s grandfather, who was

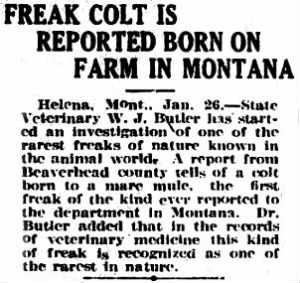

A news story about a rare fertile mule (from the front page of the January 26, 1921 issue of the Grand Forks Herald). An additional news story about the same event can be accessed here.

Another news story about a fertile mule. It appeared on page 4 (col. 1) of the May 20, 1913 issue of The Bourbon News, a newspaper published in Paris, Kentucky (source). This report is also of interest because it replicates a phenomenon described for an alleged horse-deer hybrid, which for the most part looked like an ordinary horse, but that had the hoofs of a deer protruding from its hocks.

Fertility is, in fact, very low in these animals, but there are well-documented modern cases of female mules producing offspring. Apparently, they conceive so rarely because in adulthood females have a severely depleted stock of germ cells, despite the presence of a full complement of what, under the microscope, appear to be normal oocytes in fetal females (Benirschke and Sullivan 1966; Taylor and Short 1973). There have also been many news reports about occasional fertile mare mules, a few of which are shown at right.

However, despite this deficit, some females do produce offspring after insemination by a horse or an ass. Moreover, they can support pregnancy after the transfer of embryos from either horse or ass (Davies et al. 1985). Allen and Short note that the mule, like the horse and the donkey, “will accept, gestate, carry to term, give birth to and rear successfully truly xenogeneic extraspecific foals created by the use of the technique of between-species embryo transfer.”

There seem to be no well-documented cases, however, of fertile male mules. Spermatogonial division has been observed, but mature sperm are usually completely absent. Neves et al. (2002) found that in donkeys and mules of the same size, testis weight in the former was almost five times greater than in the latter, and that seminiferous tubule volume density, tubular diameter, and total length of seminiferous tubule were all higher in donkeys. Their results strongly indicated that sterility in males is triggered by failures in autosome pairing during meiosis. The sex ratio in this cross is 56♀:44♂ (Craft 1938).

Perhaps because they propagate poorly by natural means, or possibly because they are simply the most common type of domestic hybrid, these animals were the first hybrids to be reproduced via artificial cloning.

References: Allen and Short 1997; Anderson 1939; Antonius 1950; Baahuus-Jessen 1930; Becze 1957, 1958; Brantanov et al. 1964; Chandley et al. 1974; Hifny et al. 1982; Gray 1972; International Zoo Yearbook 1961; Isaacs 1970; Kopp et al. 1986; Lloyd-Jones 1916; Makino 1955; Neves et al. 2002; Rong et al. 1985, 1988; Ryder et al. 1985; Short et al. 1974; Short 1975; Smith 1939; Tegetmeier and Sutherland 1895; Trujillo et al. 1962; Waldow von Wahl 1907; Zhao et al. 2005; Zong and Fan 1988, 1989.

By the same author: Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World, Oxford University Press (2006).

Gilding the face of universal day.

When mourning Priam to the town returned,

Slowly his chariot moved, as that had mourned.

The mules beneath the mangled body go,

As bearing now unusual weight of woe.

| Alexander the Great’s funerary chariot, pulled by 64 mules (321 B.C.): |

|

|

"At about this time the funeral obsequies of Alexander were performed. Aridaeus having been chosen by all the governors and grandees of the kingdom to take charge of that solemnity, had spent two years preparing everything that could possibly render it the most pompous and splendid funeral that had ever been seen. When all things were ready, orders were given for the procession to begin. It was preceded by a great number of road builders whose job it was to make all the ways passable through which the procession was to pass. As soon as these were leveled and prepared, the magnificent chariot — which was as much admired for its design as for the immense riches that glittered all over it — set out from Babylon. The body of the chariot rested on four golden wheels made in the Persian style, their rims plated with iron. The hubs were of gold, and represented the faces of lions biting a arrow. The chariot had four poles, to each of which were harnessed four sets of mules, each set made up of four animals, so that it was drawn by sixty-four in all. Only the strongest and largest had been chosen. They were adorned with crowns of gold and collars adorned with precious gems and golden bells."

|

|

| Mules pulling an ancient cart (Roman floor mosaic, Ostia) |

Mules (Donkey × Horse) - © Macroevolution.net

Most shared on Macroevolution.net:

Human Origins: Are we hybrids?

On the Origins of New Forms of Life

Mammalian Hybrids

Cat-rabbit Hybrids: Fact or fiction?

Famous Biologists

Dog-cow Hybrids

Prothero: A Rebuttal

Branches of Biology

Dog-fox Hybrids