Xenogenesis

Explaining a mysterious phenomenon in terms of natural law

Mammalian Hybrids

|

If a woman gives birth to a lion, the state shall be overthrown by a foreign people.

—Cicero

De Divinatione (1.53) |

Precious Nyathi

Precious Nyathi

Animals, including humans, have on rare occasion been reported to give birth to progeny not of their own kind, a phenomenon known as xenogenesis. An example is a 2017 news story about the Zimbabwean woman, Precious Nyathi, who supposedly gave birth to a frog in a hospital in her home district of Gokwe. The following is a description of the event, as excerpted from a report in the Daily Mail:

Precious Nyathi, from the village of Gokwe, in the north west of the country, was eight months pregnant when she went into labour.

But her husband, Mr Nomore, was left baffled when the 36-year-old gave birth to “something strange” which resembled an amphibious creature.

The baby later died in hospital before village elders ordered that the “frog-like creature” be burnt in front of residents.

Nomore, 39, is quoted as saying: “I rushed home and was shocked to see a frog … that my wife had delivered. At the hospital they confirmed she went into labour but were equally shocked.”

Despite receiving medical attention, the baby later died at Gokwe District Hospital, according to a local news website, The Herald.

Shocking pictures show the tiny body lying on a piece of paper on the ground.

Mrs Nyathi later told reporters: “I was expecting a child and this is what the heavens gave us. It’s a hellish experience that will haunt me all my life.”

Bullfrog, Lithobates catesbeianus

Bullfrog, Lithobates catesbeianus

Is the foregoing case simply a hoax? Or is there some other explanation? This not the first reported case of a woman giving birth to a frog. For example, in the late 1800s a notice about such an event appeared in the Winston, North Carolina newspaper Progressive Farmer (May 23, 1893, p. 3, col. 1):

Such reports have been cropping up for centuries. Thus, John Baptista Porta, writing in the sixteenth century, claimed that “A certain woman lately married, being in all men’s judgment great with child, brought forth instead of a child, four Creatures like to frogs, and after had her perfect health.”

And claims exist not only in connection with women and frogs, but also with regard to a wide variety other pairings of mother and offspring. For example, a cow giving birth to a pig, as in the notice pictured below.

A news notice (source: Omaha Daily Bee, Apr. 3, 1886, p. 5, col. 3).

A news notice (source: Omaha Daily Bee, Apr. 3, 1886, p. 5, col. 3).

In giving his account of the invasion the invasion of Greece by the army of the Persian king Xerxes (480 B.C.), Herodotus (7.57) states that after the passage from Asia over into Europe,

It would be easy enough simply to dismiss such reports as impossible, or as faked or mistaken. Indeed, xenogenetic births have served as a kind of standard of impossibility. Thus, the Bible (Job 11:12) tells us that, “An empty-headed person won’t become wise any more than a wild donkey can bear a human child.”

The notion of a mother giving birth to an animal not of her own kind does seem utterly fantastic, so much so, that when one encounters a serious news report alleging xenogenesis, it’s like a fairy tale trying to come to life. And yet, as we have seen, these reports do exist

So…such events are in fact impossible, aren’t they? Or, if not, and natural law does allow them on certain rare occasions to occur, the question becomes, How? Or is it possible that these reports are mistaking for xenogenesis something other than xenogenesis? An unaccountable event of any kind will always seem impossible or supernatural until an explanation in terms of natural law is obtained.

Possible explanations of xenogenesis

Hybridization. One fact may account for at least some of the cases of reported xenogenesis: Various well-documented scientific studies have shown that hybrids identified on a genetic basis can closely resemble one of their parents and have, in terms of appearance, seemingly little or nothing to do with the other. So, in those cases where hybrids are identical or very similar to their sires, a report of xenogenesis might result. In these cases, however, it would not be a matter a xenogenetic birth, but rather of a hybrid being reported in error as such a birth.

The next case explicitly shows that traits indicating an animal is a hybrid can be overlooked on first encounter, and yet be detected during the course of a more careful examination. The report appeared in the Fort Worth Daily Gazette (Jul. 7, 1889, p. 3, cols. 2 & 3), which had picked up the story from the Chicago Times. Entitled “A Wonderful Cow,” it originally appeared in the Toronto Globe on May 25, 1889.

The farmers of the township of Tecumseh, in South Simcoe [County, Ontario], are greatly interested at present in a strange freak of nature which has taken place in their midst, being nothing less than a cow giving birth to two lambs and a calf.

The interesting event occurred on the farm of John Henry Carter, lot 4, eighth concession line, Sunday, April 14, and when the news spread abroad so many people wanted to see the curiosities that Mr. Carter finally decided to get rid of them, and disposed of the cow and her progeny to Isaac M. Cross, an enterprising young farmer of Bondhead.

The animals were removed to Tottenham and a few days ago the Toronto Globe was invited to send up a man to see the stock and investigate independently the correctness of the story.

At a first glance the reporter was rather disappointed in the lambs, having entertained some vague idea on the subject, and hoping to see a fully developed calf with the face of a lamb or vice versa. But they appeared to his uneducated eye to be ordinary lambs and nothing more. This was at a first glance. A subsequent careful examination and comparison with other lambs of the same age showed a marked difference. Those of the unnatural parentage are larger and coarser, the wool is darker, and in toward the pelt it is like the hair on a Maltese cat; there is a tuft of hair on the breast between the forelegs similar to that of a calf. The legs are hairy and the wool is slightly streaked with hair. The mouth is dark inside and larger and firmer looking than that of a lamb and the tail is frequently thrown over the back after the manner of a calf.

They are both ewe lambs. These indications, to an experienced breeder, are of themselves sufficient to prove the authenticity of the story regarding their strange birth. There is a strong likelihood of their growing to a large size, and on both of their heads there are dark spots, indicating a possibility of horns. They are at present as large as ordinary year-old lambs.

The cow is an ordinary, common grade red cow, without any pretensions to pedigree. It is kept in the next stall to the lambs, and munches away quite contentedly.

The calf, which was born shortly after the lambs, is also in the group, but it has not the slightest claim to distinction, further than the fact that it is brother to the lambs. All four are healthy and vigorous looking.—Chicago Times.

So here we can see that probable hybrids, or at least what the reporter on careful examination pronounced to be hybrids, were initially described simply as lambs. Lambs produced by a cow would be xenogenesis, but cow-sheep hybrids produced by a cow would not.

Because in some crosses the hybrids produced vary in their appearance along a continuum connecting the sire and the dam, in such cases those closely resembling or identical to the dam would be interpreted as pure offspring even though they were genetically hybrid, whereas those identical to the sire would be reported as cases of xenogenesis. Such may be the explanation of the following report which appeared in the Napoleon, Ohio, newspaper Democratic Northwest, (Jun. 16, 1887 p. 8, col. 3), that is, the animal in question might conceivably have been a dog-cow hybrid.

Mr. Crum, the taxidermist of Liberty Center, allowed us to gaze upon his wonderful monstrosity on Monday. It is a calf, which resembles in all respects a bull-dog† pup. Mr. Crum will have the curiosity on exhibition in Napoleon Thursday, Friday and Saturday of this week. He has been offered a large sum of money for the monstrosity.

Careless description. Another explanation of reports about xenogenesis is that the person doing the reporting might know, or at least believe, that he or she is dealing with a hybrid, but nonetheless refer to it as if it were pure. So, in such cases it might seem to be a case of xenogenesis when, in reality, it was merely a matter of careless description. For example, in the report quoted below, it seems clear that the rancher De Vries thought the so-called fawn was a deer-cow hybrid, because he refers to the fact that the mother cow had been ranging in an area where deer were plentiful. And yet he still describes it simply as a deer. The newspaper joins him in this misrepresentation by calling it a fawn in the headline.

JERSEY COW GIVES BIRTH TO A FAWN

Springdale, Wash., April 27.—Giving birth to a fawn, a Jersey cow on the ranch of G. R. De Vries, five miles from Springdale, a few weeks ago provided a freak of nature never before heard of, according to De Vries.

“It is a deer in every particular,” he said. “The head is a trifle broader than that of a purebred fawn, but in every other particular it is perfect. It weighed only about ten pounds at birth, and is full of life, vigorous, and possesses all the characteristics of a fawn in its native forests. The mother is a purebred Jersey, 18 months old.”

“The hair is a mixture of white and red, and the ears lie well back on the head. I am sure it is a fawn. Its mother and grandmother have been running on the range some twelve to eighteen miles west of Springdale, on the eastern slope of the Huckleberry mountains, where deer are plentiful the year round.”

So this animal seems to have been described as a “fawn” or “deer” even though the owner and the reporter were of the opinion that it was simply a hybrid closely resembling its deer sire. The quoted report appeared in the Healdsburg, California, Enterprise (May 25, 1918).

There is also a report on record about a bear being cut from the womb of a cow in front of multiple witnesses. It appeared in the Viennese newspaper Welt Blatt (May 16, 1877, p. 7, cols. 2 and 3):

Cow Pregnant with a Bear

On the 6th of this month, a veterinarian residing at Košice [the largest city in eastern Slovakia, which in 1877 was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire], Herr Kaiser, was called to the nearby village of Buza where the pregnant cow of a farmer, named Glück, had been unable to calve despite all efforts to assist her. When even the vet couldn’t help, she had to be slaughtered. And what was inside! Instead of a calf, the assembled farm workers were amazed to find a fully formed bear cub weighing 60 Viennese pounds (i.e., 74 lbs or 33.5 kg). It had a long-haired, shaggy coat and resembled a calf only in the upper portion of its face. The nasal bones were absent and it was a cyclops with a single eye in the center of its forehead. At the urging of the veterinarian, this remarkable monstrosity was taken to Košice. [Translated by E. M. McCarthy. Original German.]

Thus, this creature, though facially deformed in a way that indicated a relationship to its bovine mother, in the article was described simply as a bear cub. So what might have been interpreted as a case of xenogenesis should probably be interpreted as a case of a rather strange hybrid that mostly resembled its father, but which also displayed a small token of cattle ancestry.

Adoption. Another explanation that might account for certain reports of this type is adoption. A wide variety of cases are on record in which an animal chooses to adopt a young one not of her own kind. On another page of this website, a wide variety of such adoptions are documented, ranging from an ordinary hen adopting ostriches to a cat adopting ducks. One of the cases documented on that page is that of a cat adopting a squirrel. So perhaps a cat adopting a squirrel is the explanation of the case about to be described.

The seventeenth-century German physician, Gabriel Clauder (1633-1691), published a brief article (Clauderi 1686) in the medical journal Ephemeridum Medico-Physicarum Germanicarum Academiae Naturae Curiosorum, an account cited by a variety of later authors (e.g., Blumenbach 1781, p. 10; Broca 1859). This report is almost as fairy-tale-like as the bullfrog report quoted above. It gives a description of what seemed to be a pure squirrel birthed by a cat. The report was cited by later scholars for at least two centuries. It reads as follows: “On a Cat giving Birth to a Squirrel—It is certain that both the highest miracles and daily novelties, as well as numerous sports and alterations, arise

However, obviously, adoption is not the explanation embraced by Clauder. He clearly thought the squirrel was a hybrid.

Clauder’s cat giving birth to a squirrel parallels various more recent cases, such as that described in the following notice, which appeared in the Tiffin, Ohio, Tribune (Apr. 13, 1876, p. 3, col. 6):

The following report appeared in the Napoleon, Ohio, Democratic Northwest (May 20, 1886, p. 1, col. 4):

Here again, adoption is the most likely explanation. It’s well known that cats will sometimes adopt rats. Mother cats have a brief period right after giving birth during which they are willing to adopt almost any animal, even birds, such as ducklings or chicks. Probably that’s what happened in this case, too.

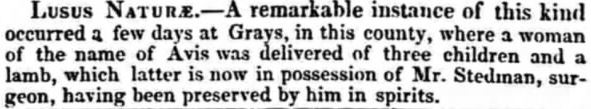

News notice about a woman giving birth to three children and a lamb (Essex County Standard, Colchester, England, July 22, 1842).

News notice about a woman giving birth to three children and a lamb (Essex County Standard, Colchester, England, July 22, 1842).

Human mothers

There are various cases, beyond the bullfrog case already quoted, in which women reportedly have given birth to animals. For example, in Welser’s chronicle of the city of Augsburg (Chronica Der Weitberuempten Keyserlichen Freyen vnd deß H. Reichs Statt Augsburg, 1595, p. 41), it is stated that a woman in that city, the wife of a certain Peter Ackermann, gave birth to a beaver in the year 1540.

There seems to be no reason why a woman would choose to surreptitiously adopt a beaver. But it might well be that she had a deformed child that was described as such, or simply that the whole case was made up, which would make this a case of careless description. It may be, too, that Welser merely heard about this beaver birth from some unreliable source and then recorded it as a factual event. Conceivably, there may have been intentional deception.

Didelphis virginianus

Didelphis virginianus

In 1909, South Carolina newspapers reported a woman giving birth to a creature that looked like a naked opossum with a stub tail. Given the locale of the reported event, the animal known as the Virginia opossum, Didelphis virginianus, would almost certainly be in question. The following report about this supposed event appeared in the Lexington, South Carolina, Dispatch (Dec. 1, 1909, p. 2, col. 3):

Monstrosity at Brunson

Negress Gives Birth to Being More

Like an Opossum than a Child

That a woman might actually give birth to an opossum is almost beyond imagination. The alternative possibility, that she produced a human-opossum hybrid, also seems beyond the pale. But in that case, the only possibility is a hoax on the part of Dr. Folk. But then it seems likely that he would be caught, given that the story says that he was making the specimen available to expert scrutiny. So in this case, explanation in terms of xenogenesis, hybridization or hoax all seem equally unsatisfactory. It’s not easy to see how a doctor would expect to gain by making up such a story.

Another South Carolina case, also certified by a doctor, involves a woman living in the country near Orangeburg, who supposedly gave birth to a headless bird. The report appeared in the journal Medical Brief (1888, vol. 16, p. 215). Supposedly, this weird offspring was headless because during her pregnancy the mother had seen the dead body of a pig whose head had been gnawed off by a buzzard. This report originally appeared in the Proceedings of the State Medical Association of South Carolina (p. 137, Charleston, 1888).

The freak was also examined by Drs. W. C. Wannamaker, Oscar R. Lowman and myself [i.e., Dr. William R. Loman]. It certainly surpasses anything ever seen by me.

Here science seems to collide head-on with fairy tale. Why would doctors collude to make up such a thing? And yet, on the other hand, how could it be true?

Women birthing puppies. Various old reports refer, too, to women giving birth to puppies. Whether hoax or hybrids, at least three cases are on record.

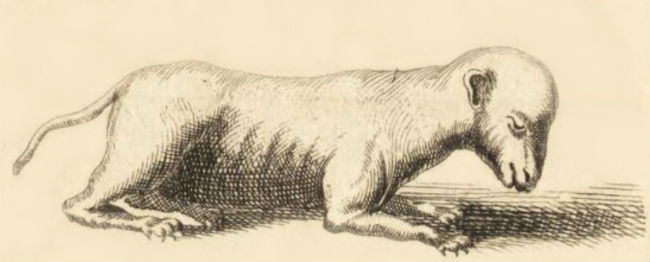

Stalpart vander Wiel’s picture of a hairless puppy, which he claimed was birthed by a woman. (source)

Stalpart vander Wiel’s picture of a hairless puppy, which he claimed was birthed by a woman. (source)

- A Dutch case. In his Observations, a compilation of rare medical cases, Dutch physician Stalpart vander Wiel (Observation LXXII) reports that in 1677 at The Hague, a midwife, Elisabeth Tomboy, assisted a woman in giving birth to a living puppy, a female. His report includes a picture (shown above). As in the case of the South Carolina opossum case just quoted, vander Wiel says this weird canine offspring was hairless (“pilis carentem”).

- A German case. Another such case is listed by the German chronicler Niels Heldvad (see his Sylva Chronologica Circuli Baltici, 1625, Hamburg, p. 265). Among other events that took place in the year 1600, he includes a record of a woman birthing puppies: “A girl at Schwabstedt [a municipality that today lies in Schleswig-Holstein] became pregnant and gave birth to three puppies. They died soon after birth. Supposedly, she had had congress with an English hound.” [Translated by E. M. McCarthy. Original German.]

- An Italian case. In his Supplementum chronicorum (Paris, 1535, p. 382), the Italian chronicler Jacopo Filippo Foresti (1434-1520) records that at Brescia in Lombardy a woman gave birth to a dog in the year 1471.

Another supposedly nonfictional case was described by the Jesuit Martin Delrio (1551-1608). If true, it would be a case of a cow-human hybrid closely resembling a human. However, with more than four centuries intervening between this supposed event and the present, the facts can never be investigated. Such is the case for nearly all such reports. At any rate, Delrio’s account (Delrio 1755, p. 149) reads as follows:

Potential interpretations

Many would simply choose to dismiss all such reports as fakes. It seems such people are confident about what’s real and there seems to be something very comfortable about a blithe lack of curiosity. Not bothering to investigate also saves a lot of work. And possibly people who respond in this way simply prefer to avoid the topic for fear of being ridiculed for taking such claims seriously. In the case of certain subjects, distant hybrid crosses among them, curiosity and, especially, any actual investigation is often equated with being an ignorant sucker. But the question remains: How can the truth of anything be known in the absence of investigation?

Rejecting some (or even many) of the cases as hoaxes seems entirely justified. One famous case, in which a woman purportedly gave birth to multiple nonhuman offspring, was eventually exposed as a hoax. It was that of the peasant girl Mary Toft, who in 1726 became famous throughout England for, it was said, giving birth to numerous rabbits. Medical professionals staked and lost their reputations on the veracity of Mary’s claims.

Mary Toft

Mary Toft(c. 1701-1763)

The Toft case was very thoroughly investigated. However, it seems that no other such cases, for example the various cases quoted above, have been evaluated with equal assiduity. And yet, proof of trickery in one such case tells us nothing about these other, as yet uninvestigated cases. It does seem that such births could in many cases be interpreted as cases of adoption, though any offspring that exhibit slightly mixed traits imbued with the mother’s nature cannot be satisfactorily explained in this way.

However, if there are any that are neither hoaxes or adoptions, then it would seem that they can most reasonably be interpreted as being due to hybridization. How else could a woman actually give birth to something like a bullfrog, as reported in the quoted notice at the top of this page? For the DNA of human parents to be altered, without hybridization, so that their offspring might take on the exact characteristics of a bullfrog would seem to require some kind of magic. Mutations of this sort are unknown. Even more implausibly, spontaneous generation would require not only the DNA but the whole organism to be produced out of thin air. That truly would be magic. These two options (mutation and spontaneous generation) seem impossible.

But, as Sherlock Holmes pointed out, “Once you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, no matter how improbable, must be the truth.” And in this case, an option that does seem highly improbable, but not impossible, does remain. One can explain this phenomenon and still remain—barely—within the bounds of natural law, if one supposes that the bullfrog offspring produced by that North Carolina mother was a hybrid. For example, what if she went for a swim at the local swimming hole at what happened to be the time of year when bullfrog sperm swarm in pond water in their billions. (Most kinds of frogs and fish engage in external fertilization, that is, males release their sperm into open water). Under such circumstances one frog spermatozoon might have found its way into her reproductive tract and fertilized a human egg, thus initiating the development of her froggy offspring. The next step would be deactivation of the human half of her offspring’s genome, resulting in the eventual birth of a hybrid that looked just like a frog. Another point in favor of this hypothesis is the fact that quite a few reports about frog-human hybrids do exist. Some of the reported individuals were even viable and supposedly lived for years.

But such cases of ostensible xenogenesis resulting from hybridization would differ from ordinary cases of hybridization because the progeny in such cases would closely resemble the sire, and have few or no traits attributable to the mother. In some reported cases the resemblance to the father was apparently so perfect that no discrepancy could easily be discerned, or at least none was recorded by the reporter. In others, as in the case quoted above, of the two sheep reportedly birthed by a cow, there may be one or a few traits shared with the mother, but perhaps, so few that at a glance the hybrid would seem to be a pure member of the father’s kind.

But if these are in fact cases of hybridization, what is happening at the genetic level? What causes the fathers’ traits to preponderate so markedly in the offspring? One possibility is that these might be rare instances of a phenomenon in which a kind of rescue occurs through genomic doubling. Thus, a cat ovum, penetrated by a squirrel spermatozoon, might rescue itself by doubling its squirrel genome and somehow eliminating or sequestering the haploid cat genome so that the fertilized zygote became diploid squirrel and developed as such. (Presumably, in Clauder’s case, quoted above, the remaining individuals in the litter, which were all ordinary cats, would then be the separate products of an ordinary insemination with cat semen.)

Alternatively, and this theory seems more likely, the event may be explicable in terms of differential activation of the two parental genomes. In any F1 cross, each parent contributes one haploid genome to the F1 hybrid. So the case presently in question might be explained if the haploid cat genome in a cat-squirrel hybrid had been entirely shut down and the squirrel haploid genome was the one that solely governed the entire course of development. This second hypothesis is more plausible because it is to some extent consistent with observation, that is, it has been repeatedly observed that in many cases a hybrid will be identical to one of its parents in certain parts of its body, but in other parts, to the other. For example, donkey-zebra hybrids often look like donkeys with zebra legs attached, which shows that the donkey haploid genome is dominating development in all parts of the hybrid other than the legs. Such observations are inconsistent with the first hypothesis, in which one parental genome is eliminated in the zygote, because there would then be no mechanism for differentially expressing parental traits in different parts of the hybrid’s body. However, if there is a switching mechanism that can turn off haploid genomes differentially in different cells, then it would be possible to produce a hybrid with zebra legs and a donkey body. The extent to which the characteristics of one parent would dominate those of the other would depend on the cross and the individual hybrid in question. But in general, some percentage of a hybrid’s traits will be attributable to Parent A, and a percentage to B, and a percentage, too, will show a mixture of A and B. Cases of ostensible xenogenesis would then be hybrids in which most maternal traits have been suppressed.

The German physician Christian Franz Paullini (1686, Obs. III, p. 186) listed various supposed cases of xenogenesis.

The German physician Christian Franz Paullini (1686, Obs. III, p. 186) listed various supposed cases of xenogenesis.

An interesting thing to consider is that if such births do occur, there may be those walking among us who seem to be wholly human, but who are in fact half non-human genetically. From the standpoint of reproduction, such people would be like carriers of a genetic defect, not affecting them, but potentially affecting their offspring. For example, the boy described by Delrio (see above) as having been birthed by a cow, might have been a cryptic hybrid and therefore the carrier of a suppressed haploid cow genome. In that case, when he grew up and married, cattle traits could have shown up in his offspring. And of course, the same would be true for any other cryptic hybrid, say a sheep produced by a cow, or a frog born of a woman. Such individuals would, however, likely be sterile as are so many (but not all) hybrids.

Another weird spin-off of these notions is that there may be “people” who, like Wilbur Whateley in H. P. Lovecraft’s short story the “Dunwich Horror,” look normal when dressed, but who bear concealed indicators of non-human parentage—fleecy legs, bristly backs, hooved toes, and so forth. Such potentialities bridge the gap between myth and everyday life.

One further point to consider is that, presumably, if mothers can give birth to hybrid offspring having traits only of their father, then it should be possible for the reverse to occur, that is, for mothers to give birth to offspring that are genetically hybrid, but who exhibit only maternal traits. This latter phenomenon would, of course, go unrecognized, because such hybrid offspring would be phenotypically indistinguishable from other offspring produced by those mothers. Again, though, the masked traits might well show up in any offspring produced by their offspring.

By the same author: Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World, Oxford University Press (2006).

Addendum: Ancient times

The cow that supposedly birthed a foal at Sinuessa in 215 B.C. (Woodcut print, Anonymous, Venice, 1493 A.D.). Source.

The cow that supposedly birthed a foal at Sinuessa in 215 B.C. (Woodcut print, Anonymous, Venice, 1493 A.D.). Source.

Such births, in which one kind of animal is birthed by another, are mentioned in various classical and pre-classical, sources. For example, the first-century Roman writer Valerius Maximus (1.6) mentions a supposed case of a horse giving birth to a hare, and Titus Livius (23.31) says a cow birthed a foal at Sinuessa in 215 B.C. Likewise, Herodotus (1.84) refers to a woman giving birth to a lion. And Pliny the Elder (The Natural History, 7.3) comments that, “Alcippe was delivered of an elephant—but then that must be looked upon as a prodigy; as in the case, too, where, at the commencement of the Marsian war, a female slave was delivered of a serpent.” This may be the same case that Isidore of Seville (On Man and Monsters) intended when he wrote

Weird events of this kind were regarded as omens. Attempts to predict the future through the interpretation of births dates to the ancient civilizations of Mesopotamia. The following are just a few of the prophecies that appear in their surviving omen lists (source: Babylonian birth omens):

- When a sheep gives birth to a lion, the armies of the King shall be powerful and the King shall have no equal.

- If a woman gives birth to a lion, that city will be taken, the king will be captured.

- If a woman gives birth to a dog, the master of the house will die and that house will be destroyed, confusion, Nergal will destroy.

- If a woman gives birth to a pig, a woman will seize the throne.

- If a woman gives birth to an ox, the king of universal rule will prevail in the land.

- If a woman gives birth to an ass, the king of universal rule will prevail in the land.

- If a woman gives birth to a lamb, the ruler will be without a rival.

- If a woman gives birth to a serpent, I will surround the house of the master.

- If a ewe gives birth to a dog, the king’s land will revolt.

- If a ewe gives birth to a beaver, the king’s land will experience misery.

- If a ewe gives birth to a fox, Enlil will maintain the rule of the legitimate king for many years, or the king will strengthen his power.

- If a ewe gives birth to a panther, the kingdom of the ruler will secure universal sway.

- If a ewe gives birth to a gazelle, the days of the ruler through the grace of the gods will be long, or the ruler will have warriors.

- If a ewe gives birth to a hind, the son of the king will seize his father’s throne, or the approach of Subartu will overthrow the land.

- If a ewe gives birth to a roebuck, the son of the king will seize his father’s throne, or destruction of cattle.

- If a ewe gives birth to a wild cow, revolt will prevail in the land.

- If a ewe gives birth to an ox, the weapons of the ruler will prevail over the weapons of the enemy.

- If a ewe gives birth to a cow, the king will die; another king will draw nigh and divide the country.