On the Origins of New Forms of Life

5.2: On the Prevalence of Vegetative Reproduction

|

| Chrysaora melanaster, a typical cnidarian |

Most plants can reproduce vegetatively. Many cultivated plants are seed-sterile and must be propagated vegetatively. These range from the Irish potato and sweet potato to flowers such as tiger lilies and some roses.

Vegetative reproduction is widespread in flowering plants (angiosperms). Gustafsson (1946–1947: 272) notes that in Scandinavia about 80% of all angiosperms are capable of vegetative propagation and that about 50% can actually spread rapidly by this means. Vegetative reproduction is also common among ferns, liverworts, and club mosses.

A very small minority of the various types of animals treated as species reproduce exclusively by vegetative means, but a much larger number are capable of both sexual and vegetative reproduction (the same could be said of flowering plants). According to White (1973: 744), vegetative reproduction, is a common occurrence among cnidarians, polyzoans, tunicates and other invertebrate groups. Hughes (1987) states that,

The tunicates of the genus Doliolum are an example (tunicates are tough-skinned marine animals related to vertebrates). Adults of this genus bud hundreds of offspring in a chain. These individuals eventually separate as sexual adults.

Sipunculid worms of the genus Aspidosiphon can reproduce by simply constricting and separating the rear end of the trunk to form a new individual.

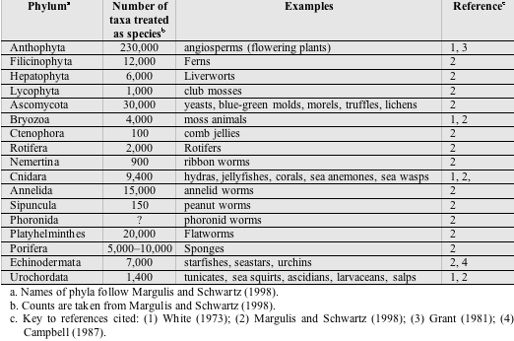

Margulis and Schwartz (1998: 361) say vegetative reproduction via budding is "almost universal in ascomycotes" a fungal phylum containing some 30,000 distinct forms treated as species. Many ascomycotes are incapable of sexual reproduction (ibid). Table 5.1 lists phyla in which vegetatively-reproducing forms are common (most such forms are also capable of sexual reproduction).

Thus, the great majority of plants and fungi — and a broad range of invertebrate animals as well — are capable of vegetative reproduction. Inasmuch as 98 percent of all animal forms treated as species are invertebrates, these facts indicate that this reproductive mode is extremely common across a broad range of organisms.

Vegetative Reproduction and Hybridization. When a new type of organism of hybrid origin is capable of vegetative propagation, it can propagate itself even when it is absolutely sterile and totally incapable of agamospermous reproduction. Even Darwin was aware of this fact. In a letter to his cousin Francis Galton dated December 18, 1875, he wrote

Table 5.1: Some phyla in which both vegetative and sexual reproduction are common:

Vegetative reproduction can, in fact, be a more viable option than sexual reproduction even in non-sterile individuals. In a forest, for example, a solid canopy of foliage might shade out sprouting seeds, while shoots attached to the mother plant might attain sufficient height to reach sunlight.

Even Darwin (1859: 43), who in the Origin largely discounted the significance of hybridization in the production of new forms of life, asserted that in plants

But Darwin neglected to mention (or perhaps did not know) that a vast variety (indeed, judging from the previous section, the vast majority) of organisms are in fact capable of propagating themselves vegetatively without the aid of human beings. Therefore, by Darwin's own reasoning, if not his assertions, hybridization must play a huge role in the production of a broad range of forms.

Among vegetatively reproducing forms, the natural production of new forms through hybridization, followed by vegetative reproduction, is limited only by the number of different viable forms hybridization can produce (whether sterile or not). Stabilization processes of this type, hybridization producing new forms capable of vegetative reproduction, must therefore be extremely common in a natural setting.