Sheep-pig Hybrids

Mammalian Hybrids

|

And so if, as you recently told me, a lamb with a pig’s head was born, then it is because a boar mated with a sheep.

—Polydore Vergil

Dialogues on Prodigies, III, xxvi* |

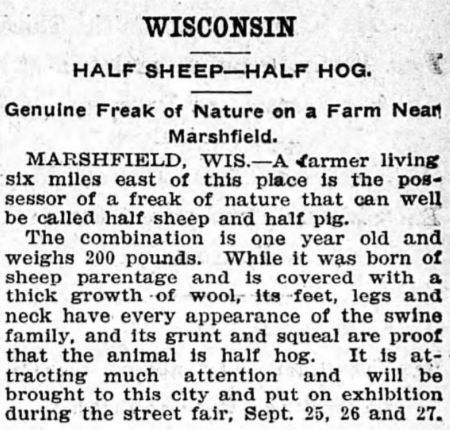

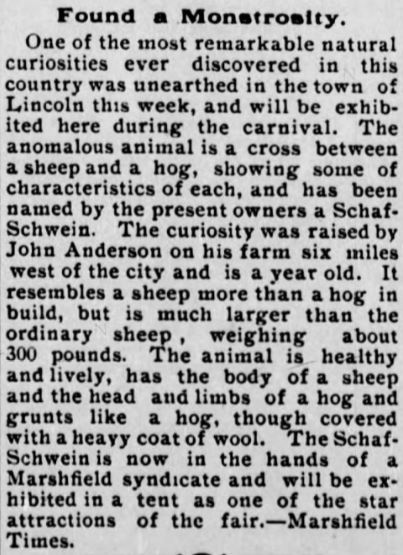

Above: A notice about a pig-sheep hybrid that appeared in the Minneapolis Journal (Sep. 24, 1902, p. 13). Below: A subsequent notice about the same animal (Wisconsin Rapids Daily Tribune, Oct. 1, 1902, p. 1).

Above: A notice about a pig-sheep hybrid that appeared in the Minneapolis Journal (Sep. 24, 1902, p. 13). Below: A subsequent notice about the same animal (Wisconsin Rapids Daily Tribune, Oct. 1, 1902, p. 1).

Caution: This disparate cross needs further confirmation, particularly from controlled breeding experiments.

It’s well documented that sheep and pigs sometimes will mate (videos >>). Indeed, even the ancient Akkadians knew that pigs and sheep do sometimes engage in such activities (Freedman 2017, p. 6). It’s a common barnyard occurrence. And text-mining of old newspapers shows that hybrids occur as well, as indicated, for example, in the reports at right.

At one time, unusual births such as pig-sheep hybrids were regularly reported in newspapers as “freaks of nature,” an English translation of the older term lusus naturae. But at about the time of the first world war, a movement arose to suppress freak shows and news reports about such creatures as well. It was distasteful and offensive, even cruel, opponents argued, to put such things before the public. The movement was successful and after the twenties, freaks rarely came before the public eye. As a result, it has been forgotten even by biologists that strange hybrids do occur. This societally enforced ignorance results in people interpreting animals that look like sheep-pig hybrids, such as the animal pictured above, as a wooly breed of pig.

For example, in 2010 stories about woolly sheep-like pigs and sheep-pig hybrids surfaced on the internet because a zoo in the UK (Tropical Wings Zoo, South Woodham Ferrers, Essex) announced that it had imported rare “Mangalitza” pigs and that they planned to breed them. Many people thought they were sheep-pig hybrids. But a BBC story assured the public that the Mangalitza was only a breed of pig:

An extremely rare breed of curly coated pig is to be bred for the first time at a zoo in Essex.

The three Mangalitza pigs, which bear a striking resemblance to sheep, arrived at the Tropical Wings Zoo in South Woodham Ferrers, just before Easter as part of a programme to save the breed.

“At first sight people perhaps think they are sheep” said education co-ordinator Denise Cox.

“It’s not until they turn around and you see their faces and snouts that you realise they are in fact pigs.”

The breed is thought to be native to Austria and Hungary.

But how did this breed of pig obtain a fleece like a sheep’s? It seems it would take some very clever breeding to start with a near naked, bristly pig and somehow select for a dense sheep-like coat of hair. And it seems no genetic study of these “pigs” has been made. After seeing this story, a Spanish geneticist whose former lab sequenced the genomes of some Mangalitza pigs said that, although the results of the study had been compared to other breeds of pig, he did not think any comparison had been made to sheep. So it seems that it has not been shown that Mangalitzas are not sheep-pig hybrids, although it’s clear from comments on the various stories around the internet that many people think they are.

The BBC subsequently published two brief stories on “Mangalitza pigs” (in these more recent articles, by the way, they use the spelling “Mangalica”).

One of these articles, by BBC World Service broadcast journalist Lucy Hooker, is about efforts to save the breed. In that article she comments that

What this comment fails to recognize is that it is well known that many breeds of domestic animals were originally produced from hybrid crosses. I discuss this fact at length, among other places, in my reference work on hybridization in birds (Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World, Oxford University Press, 2006) and elsewhere on this website. So really, it’s entirely possible that these pigs are not only a breed, but also of hybrid origin. The two are by no means mutually exclusive, as Ms. Hooker seems to suggest.

Since this is an old breed, which has apparently existed for centuries, its origin seems to be unknown. To determine the nature of that origin, it will be necessary to carry out investigations. One obvious way of gaining information about whether these animals might be sheep-pig hybrids is genetic analysis, as mentioned above. Another is experimental mating to see whether such hybrids can be produced. It is even conceivable that breeding records survive describing how the breed was produced (as is the case with many domestic breeds derived from hybrid crosses). Certainly, there are reports about sheep-pig hybrids being produced in Mexico (see below).

Other interfamilial crosses:

But the BBC’s implication that only the uninformed would suppose that these animals might be sheep-pig hybrids (i.e., “To the uninitiated it is a sheep-pig.”) seems premature. I am a geneticist and I know about hybrids, and yet I think they probably are hybrids of that sort. Moreover, I gently object to Ms. Hooker’s statement. It treats the unknown as known and therefore tends to dampen the spirit of investigation.

The other article, which is very short, was written by Tim Muffet, a reporter for BBC Breakfast. It’s really just a bit of text to accompany a video showing how these pigs are being used to restore heath land. From the standpoint of the sheep-pig question, this video is of interest primarily because it demonstrates beyond doubt that animals, such as the one pictured at the top of this page, do actually exist. Mere pictures can easily be faked. Videos, especially videos from a reliable source like the BBC, cannot.

The video evidence is also relevant because individual variation can be seen in the animals shown, with some looking identical to the very sheep-like animal shown above with its curly white fleece, to animals with sparser straight, black pelts more similar to that of European boars. This is exactly the sort of variation that occurs in a wide variety of hybrid crosses, where some individuals are more similar to one of the two parents that originally crossed to produce them, while others are more similar to the other. Such variation is especially characteristic of later-generation hybrids, the descendants of the first-generation, or F₁, hybrids produced by the original cross.

In the video accompanying Ms. Hooker’s article, it can also be seen that these animals have dark red meat like that of a sheep, not the light-colored meat typical of most pigs.

The Cuino: A sheep-pig hybrid?

F. D. Coburn

F. D. Coburn

And it seems, although these animals are treated as a rarity here in the United States, that in the mountains of southern Mexico this cross has long been intentionally produced. In his book Swine in America: A Textbook for the Breeder, Feeder & Student, Foster Dwight Coburn (1846-1924), a US farmer and government official who served as secretary of the Kansas Department of Agriculture, states the following about an animal known as the cuino, once (and perhaps still?) bred in southern Mexico (Coburn 1916, pp. 63-64):

There exists in some sections of Old Mexico a type of “hog” represented as the product of crossing a ram with a sow, and the term “Cuino” has been applied to this rather violent combination. The ram used as a sire to produce the Cuino is kept with the hogs from the time he is weaned. A resident of Mexico has given the following description of the Cuino: “The sow used to produce the Cuino belongs to any race, but as a rule to the Razor-Back family, which is the more numerous. There is never any difficulty with her accepting the ram when breeding time comes. The progeny is a pig—unmistakably a pig—with the form and all the characteristics of the pig, but he is entirely different from his dam if she is a Razor-Back. He is round-ribbed and blocky, his short legs cannot take him far from his sty, and his snout is too short to root with. His head is not unlike that of the Berkshire. His body is covered with long, thick, curly hair, not soft enough to be called wool, but which nevertheless he takes from his sire. His color is black, white-black, and white-brown and white. He is a good grazer and is mostly fed on grass [Should this trait perhaps be interpreted as the influence of sheep parentage?] with one or two ears of corn a day, and on these he fattens quickly. The Cuino reproduces itself, and is often crossed a second and third time with a ram. Be it what it may, the Cuino is the most popular breed of hogs in the state of Oaxaca, and became so on account of their propensity to fatten on little food.”

So could it be, then, that the BBC and UK zoo where the “ancient Mangalitza breed” is being “preserved” (see above) have simply been duped, and that such hybrids are being passed off by hucksters as a rare breed? Judging from Coburn’s comments, it does seem that such a possibility should be considered.

Coburn clearly assembled this passage from extracts taken from a longer article, entitled “The Cuino, A Curious Cross,” by Roger de La Débutrie (1863-1924) that appeared in another agricultural publication, the Southern Planter and Farmer (Débutrie 1900, p. 513). Débutrie’s article, which originally appeared in the respected journal The Breeders’ Gazette, reads as follows:

In a recent letter to the Gazette in relation to mule-footed hog, I mentioned the cuino, the product of a cross between a ram and a sow. Requests for particulars as to this animal have been received and I give them with pleasure. The information, however, must be very incomplete, I know, and unsatisfactory on many points, but I beg to be excused on account of the great difficulty of gathering data in this country [Mexico], the inability of most people to give satisfactory explanations from want of knowledge or observation, and the lack of any attempt to experiment in any form.

Location of Oaxaca

Location of Oaxaca

The cuino (pronounced queeno) is not considered a special race of hogs, but a hog of any race which has been improved, refined, by the introduction of sheep’s blood. I do not know if the cuino is bred in all Mexico, but he is to be met with all over this State, in the mountain districts as in the extensively cultivated valley of Oaxaca.

The ram used for crossing on sows belongs to the ordinary well-known, long-legged, light bodied Mexican sheep. He must be polled, and if not he has to be dehorned for fear he should hurt the sows. No pains are spared in his training, which begins at an early age; in fact, as soon as the lamb is weaned. When able to eat, he is taken away from his mother and the flock, and from that time forth has to live entirely in the company of hogs, never being allowed to see any of his own kind. He is pastured and fed with the drove of pigs and sleeps with them at night. With such an education and training he can not but believe himself a pig as well, and, when the time comes, has no objection to serving the sows. When the sow is in heat, he is shut up with her in a narrow pen and left as long as judged necessary. If he is slow in serving her, he is given an aphrodisiac composed of roast maize and salt, which always settles matters. This roast maize and salt is also used for this purpose in Mexico with other animals like the jack when slow in serving. The sow used to produce the cuino belongs to any race, but, as a rule, to the razor-back, which is the more numerous. There is never any difficulty of her accepting the ram when breeding time comes.

The progeny is a pig—unmistakably a pig; he has the form and all the characteristics of the pig, but he is entirely different from his dam, if she is a razor-Back. The sow in that case is, as you know, long legged, flat-ribbed heavy boned, with an immensely long snout. She runs miles from the ranch, foraging in the bush, where she is too often the prey of the leopard or the puma. She can put away bushels of corn without any appreciable effect on her carcass; in fact, I need not describe her, she is well known in your Southern States. Her pig is entirely different; He is round-ribbed and blocky, his short legs cannot take him far from his sty, and his snout is too short to root. His head is not unlike that of the Berkshire. His body is covered with long thick curly hair, not soft enough to be called wool, but which, nevertheless, he takes from his sire. His color is black, white, black and white or brown and white. He is a good grazer and is mostly fed on grass, with one or two ears of corn a day, and on these he fattens quickly. I have seen the litter of a mule-footed sow bred to a ram; her pigs were either single hoofed or cloven footed, about half of each kind.

The cuino reproduces itself, and is often crossed a second and third time with a ram. One of my neighbors, who breeds cuinos on his ranch, told me that it requires two or three introductions of ovine blood to produce a highly improved race of cuinos. I asked him if by breeding the cuino a number of times over again to a ram the progeny would not have more of the form and characteristics of the ram. He answered tha the progeny would always be hogs. Then I made the objection that, in such a case, he might, after a number of crosses, have a hog practically a pure blood sheep. To that he made no answer, only laughed.

Be it what it may, the cuino is the most popular breed of hogs in this State of Oaxaca, and became so on account of his propensity to fatten on little food.…I do not suppose any of the readers of The Gazette will ever want cuinos, having such excellent breeds of hogs, but they may like to know something about the ways of their Mexican neighbors and the extraordinary cross that produces the cuino.—Roger de la Débutrie, Huautla, Oaxaca, Mexico, in The Breeders Gazette.

A reader subsequently wrote in to the Breeder’s Gazette (1906, vol. 50, p. 836; see also: The American Veterinary Review, 1906, vol. 30, p. 1123) about the cuino. His letter and the Gazette’s response read as follows:

Again the Cuino

It is a common practice here among the poor people that want to improve their hogs. The cross is much larger than the common breed of hogs and large for any breed and they are slow to mature, not being grown until they are two and a half years old. They grow very tall and their hair is very curly and fine but otherwise they are just like the hog. The ram used is taken away from the rest of the sheep when it is small and not allowed to be with them again, but kept running with the hogs all the time.

Claudio Dunning

Hidalgo, Mexico

Remarks—This seemingly unnatural cross has been made the subject of record in these columns. This cross-bred animal is called the cuino.—Ed. Gazette.

In connection with the information just given, it’s of interest that a book published by the Mexican government on the geography and statistics of Zacatecas (Geografía y estadística del estado de Zacatecas, 1894), a state that borders Oaxaca on the south, lists among the principle animals of the state (“los principales animales que viven en el Estado”) the Cerdo Cuino, giving it the name Sus hybridus, and stating, too, its origin, as follows: “Proviene de la unión del carnero con la puerca” (“Derived from the union of a ram and a sow”).

The following is the translated text of an article that appeared in the Revista ibero-americana de ciencias médicas (1903, vol. 10, pp. 230-231) (Spanish-American Journal of Medical Sciences):

Hybrid between pig and sheep, which is known as the cuino in the Central Plateau [of Mexico], by Dr. Otón Efferd, physician at the Hospital of Mihuatlán, Oaxaca, and former resident physician at Puerto Angelo.

When I arrived in the district of Pochutla, Oaxaca, a few years ago, the inhabitants informed me that certain pigs, which differed externally from ordinary pigs, were the offspring of a ram mated with a sow, and that they were called cuinos.

At first I laughed at the zoological impossibility of this claim, and by my incredulity lost some of my scientific reputation among the inhabitants of this region. But accumulating, little by little, information about the reality of these crosses, I gained the opportunity of verifying the facts of the matter with my own eyes.

These crosses are only produced in regions with a moderate climate, since rams cannot stand climates that are too hot. It’s extremely hot in Pochutla. So the closest place to Pochutla where they produce these hybrids is Mihuatlán, which is a three-day journey on horseback.

In March of last year, I asked for leave and traveled to Mihuatlán. Very quickly, I convinced myself there that these crosses are almost certainly real.

The thing that convinced me was the fact that there are many individuals who do business renting their rams to the owners of sows. The Indians are such sage observers of daily life, and so tight with their money, that it is difficult to conceive of one of them paying even a single penny to these ram owners for nothing.

The economic motive for these crosses is that “cuinos” fatten more easily than do conventional pigs.

When I got back to Pochutla I communicated my observations to a dozen laboratories, in both the old and new worlds, inviting them to send a specialist to carry out experiments and research with regard to these revolutionary hybrids. But they all replied that this cross was an absolute zoological impossibility, that I was the dupe of Indian fables and that it wasn’t worth the bother of sending a specialist to verify things that cannot exist.

Having lost all hope of convincing a zoologist, I decided to carry out studies of my own. I resigned my positions at Pochutla and Puerto Angel, and moved to Mihuatlán forthwith.

Six weeks ago, my research into “cuinos” began. To conduct these experiments in such a manner as science truly requires would take six months. However, I am curious to know what the comments of my colleagues in the Central Bureau of Mexico might be with regard to these hybrids. People here say that these crosses are made in many parts of the Central Plateau.

If any of the readers of this journal would like to assist me in this research, which will, if the results are positive, certainly revolutionize the theory of evolution, it would be much appreciated. (From the School of Medicine of Mexico) [Translated by E. M. McCarthy. Original Spanish].

Sheep-pig hybrids: News reports

The following news report about a Mexican sheep-pig hybrid appeared in the Herald Democrat (Nov. 30, 1921, p. 5, col. 2), a newspaper published in Leadville, Colorado.

NEW ANIMAL: HALF SHEEP. HALF HOG

.

A news report about a Mexican sheep-pig hybrid appeared in the Los Angeles Herald (Oct. 3, 1908, p. 12):

MISS LINA REGISTERED AS AT

KEEPER RICE’S HOTEL

The cross between a ram and a sow is very common in some parts of Mexico, like the mulefooted or solid hoofed hog, but they puzzle the hog man of the corn belt, who is used to the Berkshire, Poland China or the red Duroc Jerseys. If [Zoo] Keeper Rice of the Eastlake Park zoo records the expressions of the eastern stock men who inspect Miss Lina, he will add considerably to his vocabulary.

At the Chicago stock yards this peculiar animal is known as a “cueno,” [sic] but at Eastlake Park Miss Lina is registered as a jabolin.

“She looks more like a what-is-it,” said Keeper Rice.

Miss Lina did not have a Pullman berth. She traveled in a biscuit box.

Middletown, New York. The Binghamton Republican: (quoted in the Ogdensburg Journal, Ogdensburg, New York, Jan. 6, 1888, p. 4; ||keypr4k) said, "A farmer near Middletown, has an animal said to be formed like a pig, but which has the horns and wool of a sheep."

Ewe x Boar

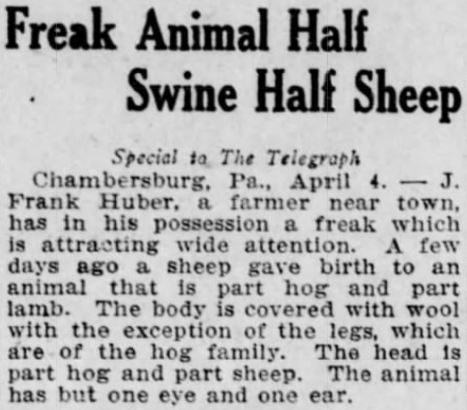

A notice about a pig-sheep hybrid that appeared in the Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Telegraph (Apr. 4, 1911, p. 2). Note that the article specifically states that a ewe gave birth to this animal, which would seem to preclude the possibility of pure pig parentage. Cyclopia, as described in this report, is quite common among hybrids, especially distant hybrids.

A notice about a pig-sheep hybrid that appeared in the Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Telegraph (Apr. 4, 1911, p. 2). Note that the article specifically states that a ewe gave birth to this animal, which would seem to preclude the possibility of pure pig parentage. Cyclopia, as described in this report, is quite common among hybrids, especially distant hybrids.

Marshfield, Wisconsin. From the Minneapolis Journal (Minneapolis, Sep. 24, 1902, p. 13; ||gtdvbw9)

HALF SHEEP HALF HOG

Genuine Freak of Nature on a Farm near Marshfield

The combination is one year old and weighs 200 pounds. While it was born of sheep parentage and is covered with a thick growth of wool, its feet, legs and neck have every appearance of the swine family, and its grunt and squeal are proof that the animal is half hog. It is attracting much attention and will be brought to this city and put on exhibition during the street fair, Sept. 25, 26 and 27.

Caruthersville, Missouri. From the Caruthersville Press (quoted in the Ripley County Democrat Doniphan, Missouri, Aug. 7, 1908, p. 1f; ||kxukq78):

Julianges, Lozère, France. L'Union des Gauches (Mende, Jun. 30, 1929, p. 1f; ||492h7ukd) said (in translation),

An early case

The French Renaissance surgeon and anatomist Ambroise Paré (1646, p. 665) mentions that “there has been seen a lamb having the head of a pig, because a boar had covered a ewe.” Translated by E. M. McCarthy. Original French: “Il s’est veu un agneau ayant la teste d’un porc parce qu’un verrat avoit couvert la brebis.” Paré’s comment may refer to an assertion made by Livy (The History of Rome, 31:6), the ancient Roman historian, who says that “at Frusino [modern Frosinone, in central Italy] a lamb was yeaned with a head like a pig.”

Tegetmeier

On his website Karl Shuker dismisses the existence of sheep-pig hybrids on the basis of an opinion expressed by naturalist William Bernhardt Tegetmeier (1816-1912) in an article in The Field in 1902. As quoted by Shuker, Tegetmeier, who had received an alleged cuino skull from a Mexican correspondent, wrote the following:

Tegetmeier

Tegetmeier1816-1912

However, a willingness to reach a decision about the existence or nonexistence of this hybrid on the basis of the appearance of its skull seems biased in the extreme. After all, in looking at any of the photos on this page, it’s blindingly obvious that this animal has a head shaped like that of a pig. So, obviously, its skull would be expected to look like a pig’s. But what if Tegetmeier had compared all aspects of its anatomy with that of a pig? Or how about just one? What if he had instead taken the pelt of one of these animals and exhibited it at the Zoological Society? Might they not have said that it was “purely and simply” the pelt of a sheep? Wasn’t this really just a blatant case of cherry picking on Tegetmeier’s part?

* Translated by E. M. McCarthy. Original Latin: Ac propterea nuper narrasti agnum suillo capite insignem natum, quod verres iniverit ovem.

Deer-cow hybrids

Deer-cow hybrids Cat-dog hybrids

Cat-dog hybrids Chicken-duck hybrids

Chicken-duck hybrids Cat-rabbit hybrids

Cat-rabbit hybrids Deer-cow hybrids >>

Deer-cow hybrids >>