Incertae sedis. An old news report about a pair of creatures like dragons or winged alligators may perhaps be best tucked away here. Read the report >>.

A Snake-chicken Hybrid?

Nerodia sipedon × Gallus gallus

|

The winged serpent is shaped like the water-snake. Its wings are not feathered, but resemble very closely those of the bat.

—Herodotus, The History

|

Serpent and cockatrice.

Serpent and cockatrice.

In myth, the cockatrice, a supposed offspring of chicken and serpent, breathed fire and killed its victims with a glance. It was one of the many composite beings compiled in medieval bestiaries and favored by Renaissance poets. Thus, Shakespeare has Juliet lament “the death-darting eye of cockatrice.” And the Duchess of York equates her heartless son, Richard III, with this baleful bird-reptile mix:

O my accursed womb, the bed of death!

A cockatrice hast thou hatch’d to the world,

Whose unavoided eye is murderous.

The weasel, it was said, was the only animal immune to this strange hybrid’s gaze. And the cockatrice itself could only die if it heard a cock crow, or if it happened to see its own reflection.

So as a whole, the cockatrice legend is far-fetched indeed. But in all this fancy is there perhaps, as is the case with so many myths, some grain of truth? Is there perhaps such a thing as snake-chicken hybrid?

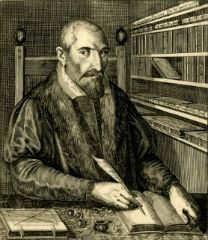

Fortunio Liceti

Fortunio Liceti(1577-1657)

The Renaissance scholar Fortunio Liceti (1577-1657) relates how his maid Julia told a tale about a chicken mating with a snake (Liceti 1665, Book II, Ch. 87, p. 253). Thus, she said, while still living with her parents, she had “more than once

Another early writer Miguel de Modina (1564, lib. 2, p. 70) said that by placing a snake into the same cage with a hen incubating eggs, you can cause the eggs to hatch snakes. But he thought this was caused by the hen's seeing the snake, not by her mating with it.

On a first reading, such claims sound like an impossibilities. But then there’s the following American news report, published in the nation’s capital, which does allege the actual occurrence of a snake-chicken hybrid, produced by a mating just such as the one Julia described all those years ago. A report about a snake-chicken hybrid appeared in a Washington, D.C. newspaper The National Tribune (Sep. 17, 1881, p. 7, col. 3), as well as in many other newspapers around the country. The snake in question would almost certainly be a Northern Water Snake, Nerodia sipedon, given that it is New Jersey’s third most common snake and its only native water snake.

A SNAKE-ROOSTER STORY

Northern Water Snake

Northern Water SnakeNerodia sipedon

Hens sometimes mate with cats.

Hens sometimes mate with cats.

So would a snake and a chicken mate? While there seem to be no reports (other than Julia’s) to support such a claim, it is in fact known that the domestic fowl will engage in sex with a wide variety of other animals, including creatures as unchicken-like as dogs, ducks and cats (see video). So why not a snake as well? After all, many biologists now believe that birds are little more than feathered reptiles, and therefore that they are more closely related to reptiles than to mammals. So perhaps a chicken and a snake would in fact be more willing partners than, say, a chicken and a cat?

The fact that the snake and chicken, according to the news report, were kept together from a young age would make such a mating more likely. Many animals will imprint on whatever creature they are regularly in contact with at an early age, that is, they will attempt to mate with that kind of animal when they reach sexual maturity.

A hen mothering a puppy.

A hen mothering a puppy.

And in comparison with other kinds of birds, hens are especially indiscriminate in forming strange liaisons. They will incubate virtually any eggs they are given and will even raise the young of animals quite distinct from themselves, such as ducklings, ostrich chicks, puppies or kittens (videos showing examples). As a result, animals raised by those hens are often imprinted on chickens when they reach maturity, that is, they will prefer to mate with chickens rather than their own kind.

Imprinting is a very well documented phenomenon in mammals and birds, but among reptiles there has been very little research in this regard, which means that it may occur in certain types of reptiles, as well, but simply be unstudied. Reptile behavior is often stereotyped as being somehow inflexible and instinctual, whereas in certain cases it’s clear they can learn and adapt (see, for example, the videos at the bottom of this page).

A news notice about snakes found in chicken eggs (Source: The Leland, Michigan, Leelanau Enterprise (June 20, 1889, p. 1, col. 3)

A news notice about snakes found in chicken eggs (Source: The Leland, Michigan, Leelanau Enterprise (June 20, 1889, p. 1, col. 3)

I myself when a small child had a wild pet toad (Bufo americanus) who, after he learned that I would supply him with food, would come when I called each evening to the door of our house. Obviously, a toad is an amphibian, not a reptile, but it seems many people regard them as being on an intellectual par with snakes.

As to the physical compatibility of the genitalia, roosters have no external sexual organs, so there is no intromission when chickens have sex. Instead, both roosters and hens have cloacae, and when their cloacae come into contact, semen is transferred from the rooster to the hen. A northern water snake, however, does have an intromittent organ, which is known as a hemipenis. A hemipenis is the male sexual organ of snakes and lizards, which are collectively known as squamates. So if anything, a squamate would be even more capable of introducing semen into a hen than would a rooster, since its organ could actually be inserted into the hen’s cloaca. Under ordinary circumstances a hemipenis remains concealed within the body, but it emerges during sex.

So, whence came this snake-headed chicken? If the news report is true, one can only imagine that Dad was the snake—to be exact, a northern water snake (Nerodia sipedon)—and that Mom was an ordinary chicken. Such a cross would be less distant that various others that have been reported. Thus, this website cites reports about a wide variety of bird-mammal hybrids. Generally speaking, a bird and a snake would be considered more closely related than a bird and a mammal. In fact, many biologists now think of birds are simply a kind of reptile.

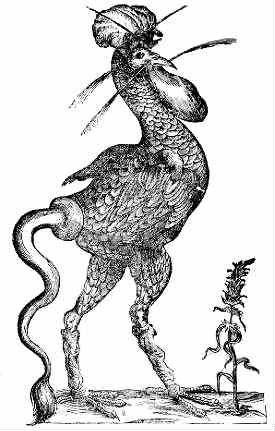

The creature Aldrovandi described as a “monstrous cock with the tail of a snake” (“gallus monstrosus cauda anguina”). From: Historiae serpentum et draconum (Records of Serpents and Dragons).

The creature Aldrovandi described as a “monstrous cock with the tail of a snake” (“gallus monstrosus cauda anguina”). From: Historiae serpentum et draconum (Records of Serpents and Dragons).

There is in fact an additional old record of such a hybrid. It appears in Ulisse Aldrovandi’s Historiae serpentum et draconum (1640, p. 62). Aldrovandi’s illustration, which appears at right, shows a creature much like an ordinary rooster, except with respect to its tail, which is like the caudal portion of a snake. Whether this old depiction is honest and accurate is difficult to say. Still, it does not seem to be particularly unusual for different hybrids produced by the same distant cross to vary in the same way as the two described on this page, that is, for one hybrid individual to have the head of one parent, but for another to have the tail. Thus, in the present cross, the Marlton animal supposedly had a snake’s head combined with the body of a chicken, while Aldrovandi’s had the head and body of a chicken combined with a snake’s tail.

Perhaps someone will attempt to replicate this weird cross and let us know the result?

By the same author: Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World, Oxford University Press (2006).

|

Baneful ere darts his poison, Basilisk, In sands deserted king.

—M. Annaeus Lucanus,

Pharsalia, 9.619 |

|

It is a basilisk unto mine eye, Kills me to look on't.

—Shakespeare,

Cymbeline, II, iv |