On the Origins of New Forms of Life

1.10: Species: Resolving the Problem

(Continued from the previous page)

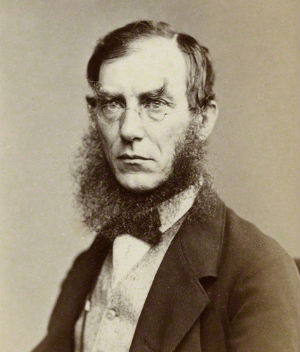

Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker

Darwin. In a letter to Joseph Hooker dated December 24, 1856, Darwin wrote

And yet Darwin certainly doesn't avoid using the word in the Origin. In fact, he uses it in almost every paragraph — even in the very title of the book. Nor does he express amusement therein when commenting on the variety of its definitions:

In point of fact, an examination of his own writings shows that he used at various times each of the various usual types of definitions himself.

Locke asserted that "men talk to one another and dispute in words, whose meaning is not agreed between them, out of a mistake that the significations of common words are certainly established, and the precise ideas they stand for, perfectly known."³ The signification of species had not been "certainly established" in Darwin's day. It has not yet been established even today, though century and a half of thought intervenes. There is no common agreement on how it should be defined.⁴ There are merely proponents of various definitions. Even the most popular of these definitions (i.e., Mayr's) has serious logical flaws making its application arbitrary (discussed in the previous section. This outcome goes against Darwin's hopes. In the Origin (1859: 484) he asserted that his theory might allow a resolution of the problems naturalists had always had with defining species:

In hoping that naturalists would cease to be "incessantly haunted by the shadowy doubt whether this or that form be in essence a species," Darwin has proved excessively sanguine. The search for the "undiscovered and undiscoverable essence of the term species" has not ceased. There has been endless debate over the meaning of the word. But its use has continued, ubiquitous not only in biology, but even in everyday conversation. Many naturalists can still be grimly serious when it comes to the issue of whether a given type of organism should be treated as a species. Different researchers use different criteria for making such decisions, just as they did in Darwin's day. For example, Mayr (1982: 171) says that when you compare the views of an ornithologist with those of an entomologist, the two will usually espouse "vastly different" definitions of species. Even among entomologists themselves there are differences in taxonomic practice. Thus, in a recent article in the journal Nature, Marris (2007: 251) observed that

Even researchers working on the same group will disagree on such points. Such the writer has certainly found to be the case for ornithologists. In deciding whether populations should be treated as species, different ornithologists emphasize different criteria. Some base their decisions on call type, others, on morphology. Many attempt to apply Mayr's definition, or some version of it. There are also many cases where morphologically identical populations are treated as separate species because they occur in separate geographic regions. For example, it is common to treat seemingly identical forms living on separate islands or separate continents as separate species. A bird could be described, then, as a different species simply because it flew from one island to another!⁶,⁷

These different interpretations of the word species, what Locke would have called the "multiplicity of its significations," produce needless misapprehension in evolutionary discussion. For example, Bullock's Oriole is often treated as a species. That is, it is assigned the binomial Icterus bullockii. However, this bird interbreeds very extensively with the Baltimore Oriole, which is also often treated as a species (I. galbula). Anyone who accepted a biological definition of species and saw that Bullock's Oriole is treated as a species might suppose it had the traits specified by such a definition. Such is certainly not the case. These two birds produce huge numbers of natural hybrids that are partially fertile in both sexes.⁸ Conversely, there are many cases where populations treated as distinct races of the same species produce infertile or even absolutely sterile hybrids. For example, many populations treated as races of the house mouse (Mus musculus) fit this description.⁹

Indeed, one wishes Darwin had refrained from giving a vague and ambiguous word such an important place in such an important book.

Restrictions in Usage. Given the many ambiguities and difficulties involved with the use of species, it might seem logical to simply drop the word from scientific debate. To speak of the "origin of a species" is to speak of the origin of a thing ill-defined, to speak of the origin of "something complicated, something that is a unity only in name" (Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, §19).10 As Francis Bacon said,

In the case of species, common practice employs a single word to refer to various entities with differing characteristics. Different people define the word in different ways. Yet, they imagine everyone is speaking of the same thing. Under such circumstances it's easy to see how "vain and innumerable controversies and fallacies" might arise.

The general usage of a word by colleagues, and by the public at large, is beyond an author's control. It is, however, possible to control usage within a given publication. On this website, I restrict usage of species, "this manifold entity for which people have but a single name" (Nietzsche, ibid).12 I do this in order to limit use of the word to those cases where its proper use can be clearly stipulated. Restricted, too, are occurrences of its derivatives (e.g., speciate, subspecies, speciation, speciose, interspecific, intraspecific, etc.), and of the various etymologically unrelated words used in place of such words (e.g., race replacing subspecies). Such words are used in only three ways:

- In referring to taxonomic treatment. For example, the phrase treated as a species is used to indicate that a group of organisms is referred to by a binomial scientific name; treated as conspecific, is used to indicate that two populations are assigned the same binomial (such usage is reasonable because, whether or not a given treatment is correct, it is always correct to state the nature of that treatment)

- In discussing how, and under what circumstances people use words of this kind (in which case the word will be italicized or placed in quotation marks);

- In quoting other writers.

In particular, the use of such words will be avoided in all cases where their use would imply a judgment is being made as to whether the entities under discussion should or should not be referred to by the word species. For such implications are, indeed, often inherent in the use of certain words. For example, no one would say that a population had "speciated" if they did not think a "species" was in question. Likewise, when biologists are of the opinion that two interbreeding populations should be treated as conspecific, they often will say they "intergrade" rather than hybridize. Many reserve the term hybridize for interbreeding between populations they think should be treated as separate species. To refer to interbreeding between natural populations, the word hybridization is always used on this website in preference to intergradation.

Species, and its derivatives, can almost always be replaced by other words of unambiguous meaning (often they can even be deleted without change in meaning). Such a course will be followed here wherever possible. Table 1.1 gives examples of various replacements for species, using other words that convey the intended meaning. In addition, a few new terms will be introduced in Section 3 to allow reference to certain distinct entities that have been lumped under the epithet species. In point of fact, it is the writer's opinion that we will never be able improve our understanding of the evolutionary process so long as we go on discussing "species" and concepts based upon a presumed existence of "species" (such as "speciation"), when species itself is a ill-defined term. Therefore, on this website, such terms and principles are viewed as fuzzy hangovers from a not entirely bygone era of thought.

Scientists have discarded, or restricted the usage of, many other words in the past. The same system of thought that gave us the word species also provided ether. The scholastics believed this "fifth element" filled the spaces between the celestial spheres. Later, scientists retained the notion of ether as a substance that filled outer space. Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, there was much discussion of its physical properties, for example, its role in the propagation of light. However, explanations of physical phenomena constructed during the early twentieth century did not make use of "ether" and scientists now use the word only (1) to refer to the common solvent and general anesthetic; (2) in historical references to former scientific debate. No scientist now discusses the nature of ether or its origins. In a similar way, the writer believes that, so long as species has no generally accepted definition, there is no reason for scientists to discuss the nature of "species" or their origins. We can construct a more precise explanation of evolution by leaving species, and all of the various ill-defined notions that word has spawned, out of the picture.

| Table 1.1: Examples of converted terminology | |

| THE PHRASE | CAN BE REPHRASED AS: |

| "the species of a genus" | "the members of a genus" |

| "some bird species" | "some bird" or "some kinds of birds" |

| "a plant species" | "a type of plant" or "a plant" |

| "various types of species" | "various types of organisms" |

In subsequent discussion it will be necessary to refer to various natural populations by their scientific names. But again, such references are not meant to imply that any judgment is being made as to proper taxonomic status. On this website, the scientific and English names used in referring to populations and specimens are based on standard taxonomies and are merely intended to designate the population in question.13 For this reason, the use of a binomial (or trinomial) does not, and is not meant to, imply the writer's opinion that it is correct to treat the populations in question as species (or subspecies). It merely means that the names are those used in a standard taxonomy to refer to the populations or types in question. On this website scientific names are names and nothing more. Certainly a population or a type can be discussed as a population or a type and be referred to by a widely accepted name without any presumption being made as to whether it should be treated as a species. This is in fact the practice followed on this website.

In general, stabilization theory assumes that certain forms are treated as species (assigned binomial scientific names) due to human decisions and that the motives for such decisions differ (1) for different types of organisms; and (2) from one human decision maker to another. Some of these motives have already been explained. Others will be specified after the necessary terminology has been introduced.

The writer is well aware that many scientists believe any population with a binomial name is a "species." But on this website the use of binomials intends no such implication — whatever the reader may infer. In fact, this entire section (Section 1) has been devoted to showing that species has no clear definition accepted by all scientists. Personally, I have no more opinion of what a "species" is than I do of what a "shrockbie" is. Shrockbie also lacks a clear definition. In fact, it has no meaning whatsoever. Of course, one can always use a word even if it lacks meaning (as I, for example, just used shrockbie). The ways in which the word species is used on this website have already been indicated. The use of this word therefore is well defined even if the word itself is not.

I hope no one will consider this practice unacceptable. To be sure, in using the word species in the ways that I have laid down, I will be doing things any other biologist does. However, in doing them, I will not share some of my colleagues' sanguine belief that species is, or ever will be, well defined. When I write, "X is treated as a species," I will merely mean "X has been assigned a scientific binomial." That is, I make a statement about the behavior of my fellow biologists (they treat it as a species). But this is not convoluted or obscure. For example, the meaning of the sentence "He gave up the ghost" is clear (i.e., it means "He died.") even though ghost is not a well-understood or well-defined entity. One need not understand the word to fully comprehend the expression's meaning. Another example is "God knows!" When someone says "God knows!" everyone clearly understands the meaning of the sentence (i.e., it means "I certainly don't know!"), but God has different meanings for different people and certainly isn't a topic for scientific debate. Indeed, "God knows!" is an expression I might well use if someone asked me what a "species" is.

Conclusion. During the rise of science in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the pre-scientific belief that "immutable species" actually did exist seems to have gone largely unquestioned. Naturalists transferred the word species (and the emphasis placed upon it) from the scholastic tradition into a new intellectual setting. Their motives were different, but they still thought some natural populations should be treated as species and others should not. The issue was never whether "species" existed, but rather what they were and how they should be defined. A system of classification, and a terminology created by followers of Aristotle and Aquinas, was taken up and extended by men of a different mind — empiricists, most of whom lacked all interest in Peripatetic philosophy.

Many modern biologists commit the same sort of error with regard to the word species that Locke said the scholastics did. The only difference is that, where a seventeenth century logician would speak of "essences," a biologist now would speak of "reproductive isolation." This is because many believe the essential characteristic of a "species" is captured in Mayr's (1940) definition of species as "groups of actually or potentially interbreeding natural populations which are reproductively isolated from other such groups." The mistake arises when they assume the typical population treated as a species is known to have this characteristic. In fact, the vast majority of all natural populations treated as species are so treated solely on the basis of the distinctive traits of specimens — it isn't known whether they are reproductively isolated. It is a mistake, then, to suppose it is known that populations so treated have this property of being isolated, or even to suppose it is known that most do. In point of fact, although there is no data bearing on isolation for most populations so treated, many such populations are known to interbreed (see Section 2). Anyone who assumes, then, that the typical population treated as a species does not interbreed with other such populations, is "liable to great mistakes," as Locke put it. For, from that assumption, it is easy to go further and believe neo-Darwinism's claim that new types of organisms are typically produced by a gradual accumulation of favorable variant traits in isolation. Ensuing sections will argue that this claim is incorrect, and, in doing so, will attempt to show that the accepted conception of evolution is fundamentally at error. NEXT PAGE >>

I think that I shall never see

A species meaning right for me.

If hybrids mate and form new seed,

Then what's a species? What, indeed?

1. Darwin (1887: vol. I, 88).

2. Darwin (1859: 44).

3. An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Book III, Chapter 11, §25.

4. Winker et al. (2007).

5. Darwin had a long dispute with his friend, the botanist Joseph Hooker, over whether the primrose and cowslip should be treated as conspecific (Darwin maintained they should be treated separately). See Darwin and Seward (1903: vol. I, 252).

6. Sometimes it seems such choices are more a matter of local custom than anything more rational. Often researchers in different parts of the world will apply different criteria in classifying taxa even within the same class of organisms. For example, in speaking of related fern diploid-tetraploid pairs, Wagner and Wagner (1980: 208) note that "in the tropics — thus far at least — the tendency has been to treat the diploids and tetraploids as the same species, but in the temperate regions they are being treated increasingly as separate species or subspecies."

7. Thompson (1992: 1038) says fossils deformed under pressure within the earth have often been treated as distinct species from undeformed specimens of the same type: "A great number of described species, and here and there a new genus (as the genus Ellipsolithes for an obliquely deformed Goniatite or Nautilus), are said to rest on no other foundation."

8. McCarthy (2006).

9. Piálek et al. (2001: 615-616).

10. Translated by E. M. McCarthy. Original German: "etwas Complicirtes, Etwas, das nur als Wort eine Einheit ist."

11. Novum Organum, First Book, §43.

12. Translated by E. M. McCarthy. Original German: "diesem so vielfachen Dinge, für welches das Volk nur Ein Wort hat."

13.The following sources were used. Mammals: Duff and Lawson (2004); Reptiles and amphibians: MavicaNET (mavicanet.ru/directory/eng/1421.html); Birds: Sibley and Monroe (1990); Fish: Fishbase (fishbase.org/search.php?lang=English); Invertebrates: University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, Animal Diversity Web (http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/); Plants: The International Plant Names Index (ipni.org/index.html) and the USDA Plant Database (http://plants.usda.gov/java/profile?symbol=SCPH).

Most shared on Macroevolution.net:

Human Origins: Are we hybrids?

On the Origins of New Forms of Life

Mammalian Hybrids

Cat-rabbit Hybrids: Fact or fiction?

Famous Biologists

Dog-cow Hybrids

Georges Cuvier: A Biography

Prothero: A Rebuttal

Branches of Biology

Dog-fox Hybrids