Ulisse Aldrovandi

Biography

EUGENE M. MCCARTHY, PHD

Ulisse Aldrovandi

Ulisse Aldrovandi(1522-1605)

Ulisse Aldrovandi. Italian naturalist and physician. Together with Conrad Gesner, he led the Renaissance movement that placed a renewed emphasis on the study of nature.

The great naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi (11 September, 1522 - 4 May, 1605) taught for many years at the University of Bologna during the latter half of the sixteenth century. A contemporary of Shakespeare, he was one of the first great specimen collectors and regularly organized expeditions for that purpose. He also brought about the creation of the university’s botanical gardens in 1568, one of the first in Europe.

Aldrovandi was nicknamed both the “Bolognese Aristotle” and the “Second Pliny.” Like Pliny, much of his life was devoted to compiling an enormous encyclopedia. Moreover, it had the same name as Pliny’s work. Aldrovandi’s Natural History was many thousands of pages long. It filled 14 folio volumes (10 published posthumously between 1606 and 1668). It had fine illustrations, and to a large extent, the descriptions were based on direct observation, unlike those of so many of his predecessors. The only comparable work of the era was Gesner’s Historia animalium.

Of Aldrovandi’s innumerable books and papers, relatively few were published in his lifetime. One of the many books he wrote was Monstrorum Historia (“A History of Monsters”), a compendium of reported human and animal monstrosities. The book included accounts not only of monstrous natural births but also of what now seem to be extremely far-fetched monsters. This sort of juxtaposition was common at the time, since there was not as yet a distinction between the literary and the scientific. If a given monster had been described by previous authors it was considered proper to mention it, whether or not it was fabulous.

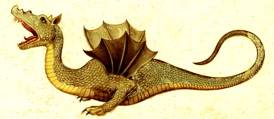

Two-legged dragon — from Historiae serpentum et draconum (1640)

Two-legged dragon — from Historiae serpentum et draconum (1640)

Another of his books mixing fable with reality was Historiae serpentum et draconum (Records of Serpents and Dragons), published in 1640. It pictured real snakes alongside creatures of questionable authenticity, such as the two-legged dragon at right (a modern-day dragon in Ohio?).

Eurasian Eagle-owl

Eurasian Eagle-owl(Ornithologiae 1599)

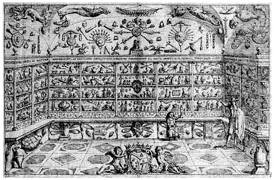

Taken together, his colossal output of writings covered all aspects of natural history. But, prior to his death, Aldrovandi’s reputation depended more on his collections than his publications. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, before the advent of public museums, private individuals would assemble collections of natural and foreign oddities, as well as artwork, of all kinds. Called “cabinets of curiosities,” or Wunderkammern, they were the precursors of modern natural history museums.

Aldrovandi’s cabinet was one of the earliest and most impressive collections of this kind, and was often described as the “eighth wonder of the world.” Although he left his cabinet to the city, it was largely broken up over the years. Only a dilapidated fraction remains on display today, at the Palazzo Poggi in Bologna (more about Aldrovandi’s cabinet >>).

Aldrovandi did more, perhaps, than anyone else to establish natural history as a field of study worthwhile in itself, without the emphasis on potential application so characteristic of earlier eras. It is for this reason that later scholars, such as Linnaeus, regarded him as the father of natural history studies.